Americans who have served in the armed forces during the decade since the 9/11 attacks have experienced the best and worst of what military life has to offer. An overwhelming majority of veterans are proud of their service (96%) and eight-in-ten feel they did important work for their country, according to the Pew Research survey of 1,853 veterans, including 712 who served after 9/11.

At the same time, wars in two countries and ongoing military commitments elsewhere in the world have required service members to be deployed longer and more frequently than in the past. These deployments have often put them directly in harm’s way: Six-in-ten veterans who served since 9/11 were deployed at least once to Iraq or Afghanistan or another combat zone.

Nearly half (47%) report that someone they knew and served with was killed in the line of duty. Six-in-ten say a comrade was seriously injured. One-in-six (16%) report they themselves were badly hurt while serving.

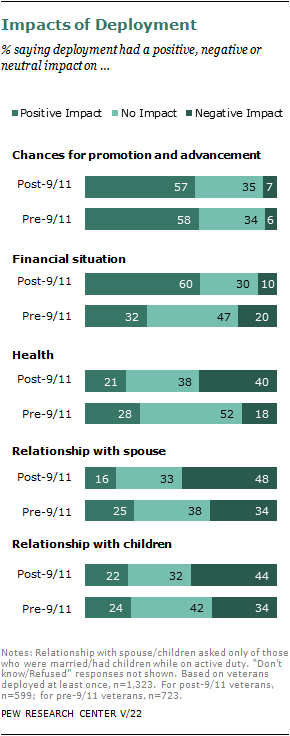

Back on the home front, nearly half (48%) say deployments have strained their relationship with their spouses and nearly as many have had problems with their children, according to the survey. At the same time, a majority (60%) say they and their families benefited financially from the extra pay and allowances that can come with a deployment.

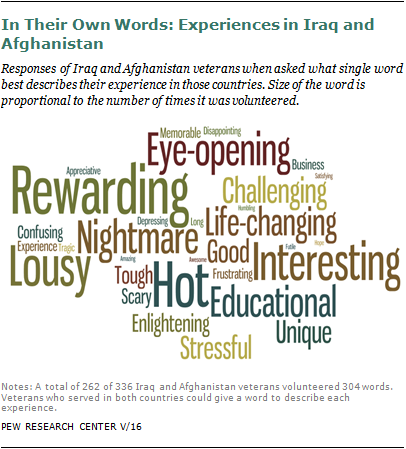

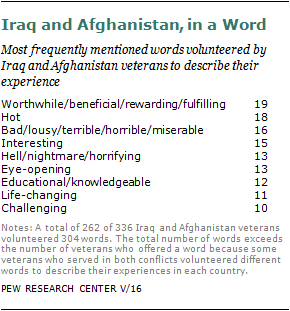

This mixed balance sheet of sacrifices and benefits snaps vividly into focus when veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were asked in the survey for the single word that best characterizes their experiences. Among the most frequently mentioned responses: “rewarding,” “nightmare,” “life-changing,” “lousy,” “interesting” and, of course, “hot.”

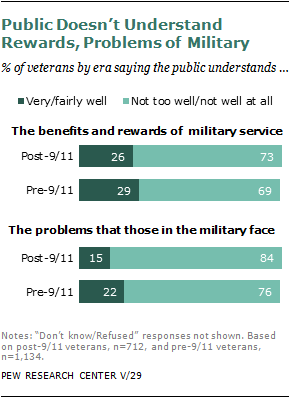

While they report that their fellow citizens have thanked them for their service, these veterans also know that most Americans have a poor understanding of military life. More than seven-in-ten recent veterans believe the public knows little of the rewards of their service, and 84% say Americans are largely unaware of the problems they and their families face. (For the most part, the public agrees: As noted elsewhere in this report, substantial majorities say Americans do not understand military life and nearly as many say they sometimes feel that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan do not affect them.)

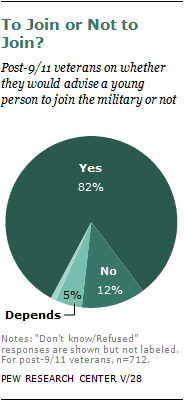

Do the rewards of military service outweigh the risks and hardships they encountered in the post-9/11 era? The responses to another survey question suggest the answer is “yes.” More than eight-in-ten recent veterans (82%) say they would advise a young person to enlist—more than the 74% of pre-9/11 veterans who say they would offer the same advice.

This chapter examines the attitudes and experiences of post-9/11 veterans and compares them with the experiences of previous generations of veterans. The first section looks at why these young men and women joined the military. The next section examines the impacts of deployment. The final section examines exposure to combat and the risks of war, and how being seriously injured or serving with someone who was badly hurt or killed in the line of duty affects views on the military and other issues.

Why They Joined

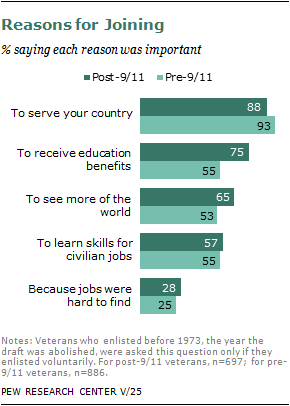

Ask veterans of any era why they joined, and the answer is usually the same: to serve their country. Nearly nine-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (88%) and a slightly larger share of those who served before the terrorist attacks (93%) say that serving their country was an important reason they joined the military.

Recent veterans are more likely than those from earlier eras to say they joined to get educational benefits (75% vs. 55% say it was an important reason). They also were more likely than earlier generations of veterans to have enlisted to see more of the world (65% vs. 53%). For those who joined on or after 9/11, nearly six-in-ten (58%) say the terrorist attacks were an important reason they volunteered.

Other reasons for joining the military are somewhat less important. Slightly more than half of all veterans say a big reason they joined the military was to acquire skills for civilian jobs, a view shared by 57% of post-9/11 veterans and 55% of those who served in an earlier era.

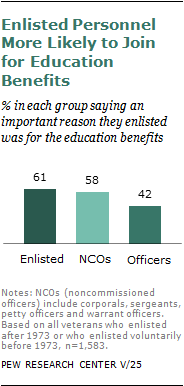

And while some see the military as an employer of last resort, only about a quarter of pre- and post-9/11 veterans say an important reason they enlisted was that jobs were scarce (28% and 25%, respectively). However, enlisted men and women are more likely than officers to have joined the military because of the lack of civilian jobs (26% vs. 14%).

Enlisted personnel also are significantly more likely than officers to cite education benefits as an important reason they joined the military (61% vs. 42%), in large part because commissioned officers are more likely to have completed college.

Deployments

What is a deployment?

For the men and women who serve in the armed forces, deployments away from home are a fact of life. After completing basic training, each member is assigned to their first “permanent duty station” in the United States or somewhere around the world. Personnel are temporarily deployed from their permanent duty station, as needed, to serve elsewhere. Deployments can range from 90 days to 15 months and vary depending on the branch. The typical deployment in the Air Force is three months, while Army soldiers can expect to be deployed for a year and sometimes longer before returning home. Personnel return to their permanent duty station after their deployment ends. They can later be deployed again. Active-duty military personnel are often transferred to a new permanent duty station and can expect to be assigned to several over the course of their military careers.

Veterans who served after 9/11 are more likely to have been deployed from their home bases during their service careers than earlier generations of military. And for six-in-ten recent veterans, at least one of these deployments was to Iraq, Afghanistan or another combat zone.

The new Pew Research Center survey also found that more than eight-in-ten recent veterans (84%) say they were deployed at least once while serving—and nearly four-in-ten (38%) say they have been deployed three times or more. Only 16% say they have never been deployed, with about half of these having served on active duty for less than three years.

In contrast, about three-in-ten pre-9/11 veterans report they were never deployed, double the proportion of recent veterans (31% vs. 16%). Even among those who served during the Vietnam War, nearly three-in-ten (28%) say they never received orders to deploy.

Still, multiple deployments have been relatively frequent in past wars. Four-in-ten Vietnam-era veterans (42%) and about a third of all surviving veterans of the Korean War and World War II (35%) say they were deployed three times or more during their military careers.8

The survey found that deployments bring extra rewards—and greater hardships. Among the benefits most frequently cited by post-9/11 veterans: additional pay, enhanced opportunities for promotion and the sense they were doing something important for their country.

At the same time, these recent veterans acknowledged the hazards of deployment: strains on their marriage and families and the greater likelihood that they could be killed or injured or have to face other health-related hazards.

The Benefits of Deployment

Among all veterans who had been deployed, the post-9/11 veterans are nearly twice as likely as earlier generations of military to say their deployment has had a positive impact on their financial situation (60% vs. 32%).

In particular, recent veterans who served in combat zones report they had benefited financially from deployments. Among these combat veterans, about two-thirds of all post-9/11 veterans (67%) say deployments have helped them financially. In contrast, about four-in-ten (43%) of those who have not been in combat say their deployments have positively affected their finances.

It’s not surprising that service members say they got a financial boost from deployments. Depending where they are sent, troops can qualify to receive Hazardous Duty Incentive Pay, Imminent Danger or Hostile Fire Pay and a cash bonus if they re-enlist while serving in a combat zone. In addition, they do not have to pay federal income tax on their military earnings while serving in a combat zone.

Deployments benefit service members in more ways than just in their pocketbooks. Regardless of when they served, veterans agree that deployments are the fast track to promotion in the military. A majority (57%) of post-9/11 veterans say their deployments had a positive impact on their chances for advancement in the military, a view shared by 58% of deployed veterans who served before 9/11.

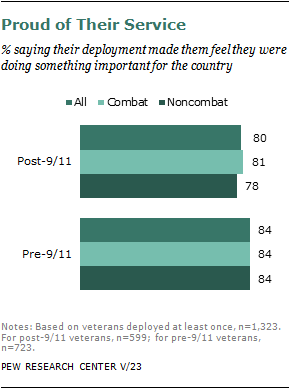

Regardless of era, veterans also agree that deployments made them feel they were doing something important for their country, a view expressed by 80% of all post-9/11 veterans and 84% of those who served earlier.

Even recent veterans who have not been deployed to the front lines felt they were doing something significant: 78% of those sent to noncombat areas say their deployments made them feel like they were engaged in work vital to the nation’s interests, a feeling shared by 81% of those who served in combat zones.

Negative Impacts of Deployments

The burdens of deployment in the post-9/11 era have fallen particularly hard on married service members.

Nearly half of all recent veterans (48%) who were married while in the military say their deployments put a strain on their marriages, compared with 34% of married veterans in previous eras. An additional 16% of post-9/11 veterans say the impact of long separations on their marriages was positive; 33% report no impact.

Deployment to a combat zone may be linked to higher levels of family discord among post-9/11 veterans. Among those who served in a war zone, about half (51%) say that their deployments hurt their marriages, compared with 41% of those posted only to noncombat areas. However, the small sample size makes it difficult to draw a firm conclusion about the impact that serving in combat has on marital relations.9

Defining the Eras

Two survey questions were used to classify veterans by the era in which they served: the date they entered the service, and the length of time that they were in the military. Based on these two pieces of information and the official starting and ending dates of major U.S. conflicts, veterans were assigned to one of five eras:

World War II/Korea (1941-53) consists of all those who served in the military between the start of U.S. involvement in World War II and the end of the Korean War. Sample size: 269.

Post-Korea/Pre-Vietnam (1954-63) includes those who entered service after the Korean War and were discharged before the start of the Vietnam War. Sample size: 144.

Vietnam (1964-73) includes those who served in the Vietnam. Sample size: 522.

Post-Vietnam/Pre-9/11 (1974 until Sept. 11, 2001) includes those who entered the military after the Vietnam War and were discharged before 9/11. Sample size: 198.

Post-9/11 (2001-) includes those who have served at any point after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, regardless of when they enlisted. Sample size: 712.

Deployments also have had a negative impact on the relationship between many military parents and their children, recent veterans say. Among post-9/11 veterans who were parents while they served, slightly more than four-in-ten veterans (44%) report that their deployments had hurt their relationship with their children, compared to 34% of parents who served before 9/11. These strains were felt in roughly equal proportions by post-9/11 parents who served in combat zones (45%) and in noncombat areas (41%).

Deployments place additional burdens on those who serve. Among all veterans who had been deployed at least once, four-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (40%) say their health suffered from these assignments, compared with 18% of those who served in earlier eras.

Not surprisingly, recent veterans who served in battle areas are significantly more likely than veterans who had been sent to noncombat areas to say their deployments have had a negative impact on their health (44% vs. 31%), in part because of the greater likelihood of being badly hurt in combat. But this is not the whole explanation: about four-in-ten recent veterans (39%) who were not seriously injured while serving in a battle zone say their health suffered from the deployment.

A different question produces corroborating evidence that deployments may be hazardous to a veteran’s health. When post-9/11 veterans were asked to rate their current health, about a third (34%) of those who had not been deployed to a combat zone say it is “excellent,” compared with 21% of those who had served in a battle area.

Understanding the Military

America’s veterans agree: The public just doesn’t understand the military. Seven-in-ten veterans say the public has an incomplete appreciation of the rewards and benefits of military service. And about eight-in-ten say the public does not understand the problems faced by those in the military or their families.

The belief that the public knows little about military life is broadly shared by veterans of all eras. An overwhelming 73% majority of those who served after 9/11 say the public understands the rewards and benefits of military service either “not too well” (49%) or “not well at all” (23%).10 A similar proportion of other veterans agree (69%).

A somewhat larger proportion of post-9/11 veterans (84%) believe that Americans have little awareness of the problems faced by those in the military, a view shared by a somewhat smaller share of those who served before the terrorist attacks (76%).

Those with recent, personal exposure to combat and its harsh consequences feel most strongly that the public does not understand the burdens of service. Among post-9/11 veterans who knew and served with someone who was seriously injured, nearly half (46%) say the public understands their problems “not well at all.” Among post-9/11 veterans who did not know anyone who was injured, three-in-ten (30%) express this view.

Respecting the Military

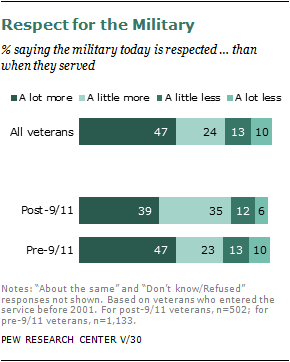

Judged by national surveys, Americans hold the military in high regard. A recent Gallup survey in June found that the military topped the list of America’s most trusted institutions. Nearly eight-in-ten (78%) expressed confidence in the armed forces—fully 30 percentage points higher than the share that had similar trust in organized religion and at least double the proportion that had similar faith in the medical system, the Supreme Court or the presidency.11

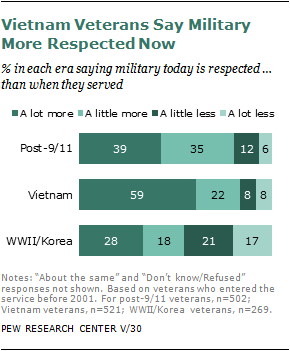

The new Pew Research survey asked veterans of different eras if they thought the public had more or less respect for the military today than it did when they served.

The answers are revealing. Overall, about seven-in-ten say the public has “a lot more respect” (47%) or “a little more respect” (24%) for the military now than when they served. But results sharply differ by era of service.

Overall, majorities or pluralities of veterans regardless of era believe today’s veterans are respected more than when they served, including 81% of Vietnam-era veterans, 74% of those who entered the service before 9/11 and served at least briefly after the terrorist attacks,12 and 46% of all Korean War and World War II-era veterans.

The oldest and youngest generation of veterans see only modest differences in the way the public respects the military today compared with the views of the country when they served. Among those who served during World War II or the Korean War, nearly three-in-ten (28%) say today’s veterans are respected “a lot more” than they were.

The youngest veterans—those who joined the military before 9/11 but served after the terrorist attacks—also see relatively small changes in the way the public views their service: about a third (39%) say respect has increased “a lot” since they served.

Together, these findings likely reflect the relatively high regard that the military enjoyed during the World War II era and again today.

A different story emerges from the findings on this question among the Vietnam-era veterans. About six-in-ten veterans who served in Vietnam (59%) say today’s armed forces are respected “a lot more” than the military was when they served.

These judgments are in sync with contemporaneous survey data from that era. A Gallup poll conducted in May 197513 found that 58% of the public expressed confidence in the military. That is fully 20 percentage points below Gallup’s finding in June of this year.

Injuries, Casualties and Combat

Six-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (60%) say they served in a combat zone, compared with 54% of those who were in the military during the Vietnam era and 53% of surviving veterans of the Korean War and World War II.14

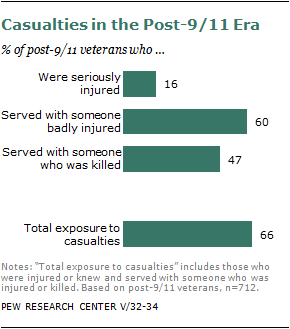

Overall, about one-in-six post-9/11 veterans (16%) report they were seriously injured while serving in the military, and most of these injuries were combat-related. One-in-ten pre-9/11 veterans was seriously injured (10%), but a higher proportion was hurt in combat (75% vs. 60% among recent veterans).

The higher rate of serious injuries in the post-9/11 era (16% vs. 10% for other veterans) should be interpreted cautiously. But it does mirror a larger truth: According to Department of Defense statistics, those fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq are dying at a significantly lower rate than their comrades-in-arms who fought in Vietnam, Korea or World War II. Advances in medical treatment mean that more injured troops in the post-9/11 era are surviving what were once fatal wounds. While serving in the military is still risky, it is less lethal now on and off the battlefield than it was in previous war eras. (A complete analysis of casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan compared with previous conflicts can be found in Chapter 6.)

Exposure to Casualties

Despite technological and medical advances, war is still hell for the men and women who are asked to fight. Six-in-ten say they knew and served with someone who was seriously injured. About half served with someone who was killed. And as noted earlier, about one-in-six were themselves seriously injured in the line of duty.

When these individual findings are combined, the result is an overall measure of exposure to the casualties of war in the 9/11 era. According to the survey, two-thirds of all recent veterans say they were seriously injured, knew someone who was injured or lost a comrade in the line of duty—a proportion that increases to 73% among combat veterans in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The survey found that about seven-in-ten of those who served in combat say someone they knew and served with was seriously injured. Nearly half of all recent veterans (47%) say someone they knew or served with was killed while on duty, a proportion that rises to 62% among those who were in combat.

Casualties also can occur away from the battlefield.15 Among post-9/11 veterans who never served in a combat zone, about one-in-six (16%) were seriously injured in training accidents or while performing other military-related duties. In addition, about half (49%) of recent veterans who were never in combat say they knew and served with someone who was badly injured, and 26% report they served with someone who was killed while serving.

Overall, post-9/11 veterans give high marks to the medical treatment that injured armed forces personnel receive in military hospitals. Nearly three-quarters (74%) rate the care as either “excellent” (22%) or “good” (52%).

Among recent veterans who were seriously injured or knew someone who was, nearly as many (72%) gave high marks to stateside medical care of wounded military personnel. And veterans who served in previous eras were just as approving: 70% rate the treatment as excellent or good.

The Consequences of Casualties

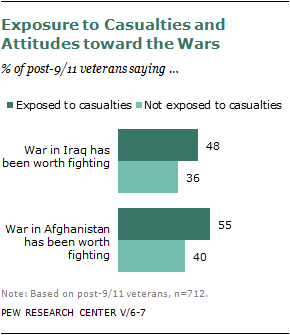

Personal experiences with war casualties strongly shape the way 9/11 veterans view some elements of their service as well as their attitudes toward the military.

Exposure to casualties has a larger impact on how veterans view the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as their judgments about the importance of their own service.

Service members who were seriously wounded or knew someone who was killed or seriously wounded were more likely to say the war in Iraq is worth fighting than those who had no personal exposure to casualties (48% vs. 36%).

Exposure to casualties had an even larger impact on attitudes toward the war in Afghanistan: 55% of those exposed to casualties say Afghanistan has been worth the cost to the United States. In contrast, about four-in-ten (40%) post-9/11 veterans not exposed to casualties say Afghanistan has been worth it.

However, the survey found that wartime experiences had little, if any, impact on ratings of President Obama’s performance as commander in chief. Slightly more than four-in-ten (42%) of those who had personal experience with casualties approve of the job that Obama is doing as commander in chief, compared with 47% of those with no exposure.

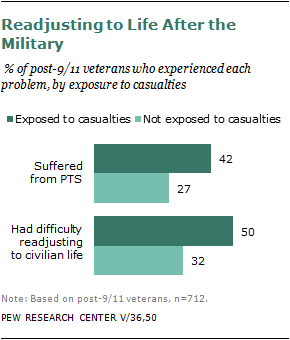

Exposure to casualties also has a profound impact on a veteran’s emotional well-being, the survey found. Predictably, recent veterans exposed to casualties while in the service were more than twice likely as those who were not exposed to say they experienced an emotionally traumatic or distressing event while serving (54% vs. 22%).

Veterans who had been exposed to casualties are also more likely to say they suffered from post-traumatic stress as a result of their experiences in the military (42% vs. 27%).

Perhaps as a consequence, post-9/11 veterans who had been exposed to casualties had a more difficult time rejoining civilian life once they left the military. Fully half (50%) say their readjustment to life after the military was difficult, compared with less than a third (32%) of those who were not exposed to casualties.

In key ways, today’s veterans are reliving some of the same difficulties that confronted earlier generations of soldiers. For example, 37% of those who were exposed to casualties in Vietnam report they had a hard time adjusting to civilian life, compared with only 5% of those who were not.

Yet exposure to the bloody side of war did not seem to change how post-9/11 veterans felt about their military experience: More than nine-in-ten of both groups say they were proud of their service, regardless of whether they had been injured in the line of duty or had served with someone who was seriously injured or killed.

The Fog of War

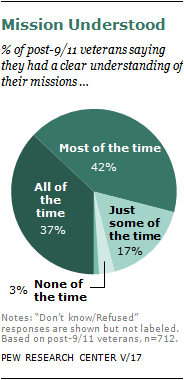

Most of the men and women of the military understand the missions they are assigned to undertake. About eight-in-ten post-9/11 veterans say they understood their missions “all of the time” (37%) or “most of the time” (42%). Only about one-in-five (20%) say they had a full understanding of their assignments just some or none of the time.

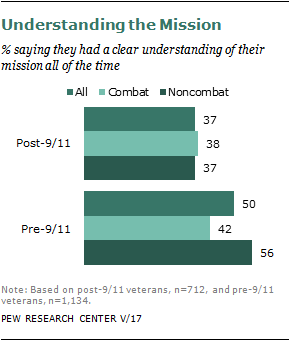

At the same time, post-9/11 veterans are less likely than those who served in earlier eras to say they always had a clear understanding their assigned missions and the role they would play in it (37% vs. 50%).

But this “understanding gap” narrows dramatically when the comparison is made only between those personnel who served in combat. Nearly four-in-ten combat veterans in the post-9/11 era (38%) say they understood all of their missions, roughly similar to the 42% of pre-9/11 veterans who served in combat areas and virtually identical to the 37% of recent veterans who were in not in combat.

The similarities in mission awareness between combat and noncombat troops in the post-9/11 period represent a change from previous eras. Among all pre-9/11 veterans, the majority (56%) of those who were not in combat understood all of their assignments, compared with only 42% of combat veterans. For example, among all noncombat veterans of the Vietnam era, 54% fully understood their missions, compared with 35% of those who were in combat.

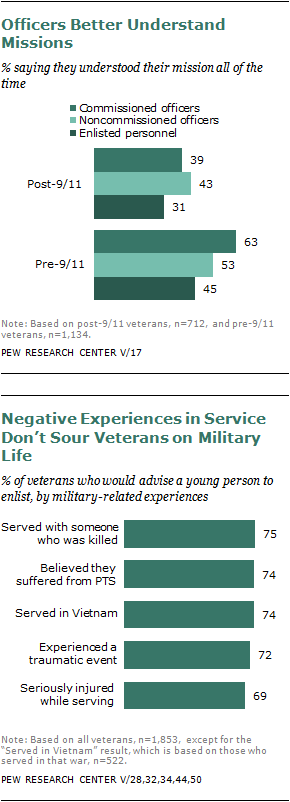

In the post-9/11 era, noncommissioned officers—a classification that includes corporals, sergeants, warrant officers and petty officers—are somewhat more likely than enlisted personnel to say they understood all their missions (43% vs. 31%), a view shared by 39% of commissioned officers.

Rank mattered even more in earlier eras: Nearly two-thirds of the pre-9/11 officers (63%) but only 45% of enlisted personnel say they always had a clear understanding of their missions.

Advice to the Young about Joining the Military

Should a young person today serve in the military? America’s veterans agree the answer is “yes,” a view that substantial majorities share regardless of the era they served, their combat experience or direct exposure to casualties.

More than eight-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (82%) say they would advise a young person close to them to join the military. Only 12% would answer no and 5% say it depends on the individual. These views cross the generations: 74% of those who served before the terrorist attacks would advise enlisting, including an identical proportion of Vietnam-era veterans.

This endorsement of the military remains solid when a veteran’s experiences in the service are taken into account. For example, 84% of all post-9/11 veterans who served in a war zone would advise a young person to join—as would 80% of those who completed their service in less dangerous areas.

Exposure to casualties may strongly shape other views but has only slight impact on a recommendation to enlist. Similar proportions of post-9/11 veterans exposed to casualties and those who were not would advise enlisting (82% vs. 79%), as would 78% majorities of those who think the wars in Afghanistan or Iraq are not worth the cost.

Perhaps the most striking endorsement of military service comes from veterans of any era who were seriously injured while serving. Among this group, about seven-in-ten (69%) say they would urge a young person to enlist, compared with 76% of those who were not injured.

In their Own Words

A different kind of survey question asked veterans to express in their own words what it was like to serve on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan. A total of 262 of 336 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans volunteered 304 words.

Taken together, these veterans offered a mixed view of their service. A total of 19 say their experience was rewarding, beneficial or worthwhile. Thirteen say it was a “nightmare,” “horrifying” or simply “hell.” Among the other most frequently used words: “hot” (18), “interesting” (15), “eye-opening” (12) and “educational/ knowledgeable” (12).