This generation of young adults has sometimes been labeled the “boomerang generation” for its proclivity to move out of the family home for a time and then boomerang right back. The Great Recession seems to have accelerated this tendency. The Pew Research survey found that among all adults ages 18 to 34, 24% moved back in with their parents in recent years after living on their own because of economic conditions.

Of course some young adults were already living at home for reasons that may or may not have to do with the weak economy. The youngest adults—ages 18 to 24—are more likely to fall into this category. According to the survey 40% of 18- to 24-year-olds currently live with their parents, and the vast majority of them say they did not move back home because of economic conditions (in fact many of them may have never moved out in the first place). Among those ages 25 to 34, only 12% currently live with their parents, but another 17% say they moved back home temporarily in recent years because of economic conditions.

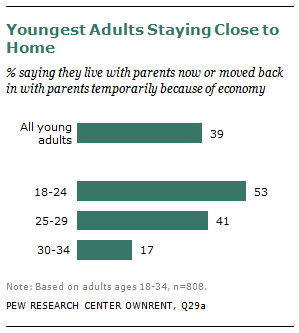

Overall, 39% of all adults ages 18 to 34 say they either live with their parents now or moved back in temporarily in recent years, but there is considerable variance by age. Among 18- to 24-year-olds more than half (53%) live at home or moved in for a time during the past few years. Among adults ages 25 to 29, 41% live with or moved back in with their parents, and among those ages 30 to 34, 17% fall into this category.

Young men and young women are equally likely to fall into this category—40% of men ages 18 to 34 and 38% of women in the same age group either live with their parents now or moved back in for a time because of the economy. While there is no significant difference in the share of young whites, blacks or Hispanics who are living with their parents, young whites and Hispanics are much more likely than young blacks to have moved back in with their parents temporarily because of economic conditions.

Educational status is linked with living arrangements for young adults in their 30s, but not for those under age 30. Among 30- to 34-year-olds, college graduates are significantly less likely than non-college graduates to be living at home (10% vs. 22%). Among adults ages 18 to 29, educational status is not related to living arrangements: 42% of college graduates in this age group live with their parents, as do 50% of those who are currently enrolled in school and 49% of those who are not enrolled and do not have a college degree.

Employment status is correlated with living arrangements among young adults. Nearly half (48%) of adults ages 18 to 34 who are not employed either live with their parents or moved in with them temporarily because of economic conditions. Among those who are employed full or part time, 35% are living at home or moved back for a time. Young adults who are not just working but feel they are in a “career” are among the least likely to be living with their parents. Only 17% of these young adults are living at home. By comparison, 42% of young working adults who say their job is a stepping stone to a career or just a job to get them by are living with their parents or have done so in recent years.

Similarly, working young adults who are not satisfied with their wages have a greater likelihood of living at home. Among those who say they do not get paid enough for the kind of work they do, 41% are living with their parents or moved back in for a time because of the economy. Among those who say they do get paid enough, only 27% are living at home.

A Widespread Phenomenon

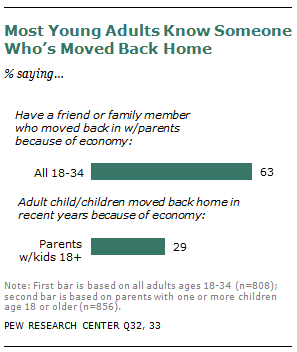

Whether or not they live with their parents, most young adults say they have a friend or family member who has moved back in with their parents in the past few years because of economic conditions. Among all 18- to 34-year-olds, 63% say they know someone who had to move back home because of the economy.

Young adults who are themselves living at home (or who moved back in temporarily) are more likely than others to know someone in the same situation. More than seven-in-ten young adults who are living with their parents say they have a friend or family member who moved back home in recent years. This compares with 58% of young adults who are living on their own.

Roughly one-in-three parents of adult children (29%) say that an adult child of theirs has moved back in with them in the past few years because of economic conditions. Mothers of adult children are more likely than fathers to report that their adult child has moved back home in recent years (35% vs. 21%). And Hispanic parents are more likely than black or white parents to say they’ve had an adult child move back home recently.

There is no clear socio-economic pattern to this. Parents with annual household incomes of $100,000 or more are just as likely as those with incomes under $30,000 to say their adult child has moved back home because of economic conditions.

How Living at Home Affects Outlook, Relationships

Parents who say their adult children have moved back in with them are just as satisfied with their family life and housing situation as are those parents whose adult children have not moved back home. And the same can be said of the adult children. Fully 68% of young adults ages 18 to 34 who are living with their parents or moved back in temporarily because of economic conditions say they are very satisfied with their family life. This compares with 73% of young adults who are not living with their parents (a statistically insignificant difference). Similarly, 44% of young adults who live with their parents say they are very satisfied with their present housing situation. A similar proportion (49%) of young adults who live on their own say the same.

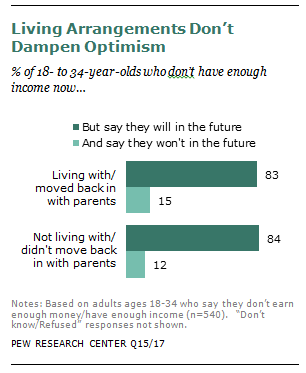

And living with mom and dad hasn’t dampened the economic optimism of these young adults. Overall, young adults are much more optimistic than middle-aged and older adults about their financial future, in spite of the tough economic times and difficult labor market they are facing. Young adults who are currently living with their parents or moved back in temporarily because of economic conditions are less likely than their counterparts who are living on their own to say they have enough money to live the kind of life they want. Among those ages 18 to 34, 21% say they have enough money now, compared with 38% of young adults who are not living with their parents.

However, among those young adults who say they do not have enough money now, equal shares of those who live with their parents and those who do not are optimistic that they will earn enough in the future—83% of those who live at home (or moved back temporarily) and 84% of those who live on their own say they will have enough money in the future to live the kind of life they want.

Living at home with mom and dad may be an economic necessity for many young adults, but how does it affect their relationship with their parents? Survey findings suggest that the effect is more positive than negative. Overall, 34% of adults ages 18 to 34 who live with their parents or move backed in temporarily because of economic conditions say that living with their parents at this stage of life has been good for the relationship. Only 18% say this has been bad for their relationship with their parents, and 47% say it hasn’t made any difference.

Views on this differ, however, based on age and on an individual’s circumstances. Among young adults who are living with their parents, the youngest ones (ages 18 to 24) tend to give the most upbeat assessment of how living at home has impacted their relationship with their parents. Fully 41% of these 18- to 24-year-olds say living at home at this stage of life has been good for their relationship with their parents. Only 12% say it’s been bad for their relationship, and 47% say it hasn’t made a difference. Opinion is more evenly split among those ages 25 to 34: 24% say living at home has been good for their relationship with their parents, an equal share (25%) say it’s been bad for their relationship, and 48% say it hasn’t made a difference.

Young adults who say moving back home was an economic necessity have a more negative view of how this living arrangement has affected their relationship with their parents. Among those who say they moved back in with their parents after living on their own, 25% say this was good for their relationship, 24% say this was bad for their relationship, and 50% say it hasn’t made any difference.

The views of young adults who are living with their parents but say they didn’t move in because of the economy are much more positive. Nearly half of these young adults say living with their parents at this stage of life has been good for their relationship. Only 8% say this has been bad for their relationship, and 44% say it hasn’t made any difference.

The Rise of Multi-Generational Households

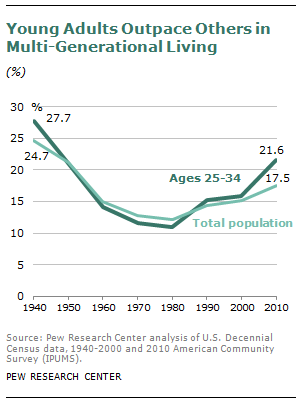

Young adults moving back in with their parents is part of a broader trend toward multi-generational living. The number of Americans living in multi-generational households has been increasing steadily since 1980. Demographic forces such as delayed marriage and a wave of immigration have contributed to the increase.

During the recent recession, which officially began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009, the number of Americans living in multi-generational households rose sharply. A 2011 Pew Research Center report found that from 2007 to 2009 the increase in the number of Americans living in multi-generational households—from 46.5 million to 51.4 million—was the largest increase in modern history.

The 2011 report linked the rise in multi-generational living to the economy. Unemployed adults, whose numbers grew substantially during the recession, are much more likely than those with jobs to be living in a multi-generational household. The recession’s impact on personal finances also likely contributed to the increase. From 2007 to 2009, median income went down and poverty rates went up. Over this period, the share of Americans living in multi-generational households increased more among young adults than among other age groups. By 2009, 21% of those ages 25 to 34 were living in multi-generational households, and the share had crept up even higher by the end of 2010 (to 21.6%). Among the total population, 17.5% were living in multi-generational households in 2010, up from 15.2% in 2006.

The Economics of Multi-Generational Living

[01-06]

Young men and young women are equally likely to say they do chores around the house and pay rent. However, more young women than young men say they contribute to household expenses (84% vs. 67%).

Young adults ages 18 to 24 are much less likely than their slightly older counterparts to say they pay rent or contribute to household expenses. Nearly half (48%) of those ages 25 to 34 who are living with their parents or moved in temporarily during tough economic times say they have paid rent to their parents. Only 25% of those under age 25 say they pay rent.

Overall, the median income for multi-generational households is higher than the income for other types of households. This is attributable in part to the fact that there are more potential breadwinners in multi-generational households than in other households. After controlling for household size, the income of multi-generational households is actually slightly lower than that of other households.

While multi-generational households may not provide higher incomes, they do appear to serve as an economic safety net. Americans who live in multi-generational households are less likely than those who live in other households to live in poverty. According to Census Bureau data, in 2010, 12.6% of those living in multi-generational households lived in poverty. This compares with 15.7% of those living in other households.

The gap is especially wide among young adults, suggesting that living in a multi-generational household may be particularly beneficial for this age group. Fewer than one-in-ten 25- to 34-year-olds (9.8%) who resided in a multi-generational household in 2010 lived below the poverty line. By contrast, 17.4% of those who lived in another type of household lived in poverty.

Among middle-aged adults, the difference in poverty rates between those who lived in a multi-generational household and those who didn’t were much smaller. For example, among those ages 35 to 44, the poverty rate was 12.2% for those living in a multi-generational household and 12.4% for those living in other households. The gap is somewhat wider among older Americans, though still not as dramatic as the gap among 25- to 34-year-olds.

Financial Connections across Generations

Given the complexities of family economics along with tough economic times, it is not surprising that many young adults say their current financial situation is linked to their parents’ financial situation. One-in-four adults ages 18 to 34 say there is a “great deal” of linkage between their financial situation and that of their parents. A similar proportion (23%) say there is “some” linkage between their financial situation and their parents’. The remaining 51% say their financial situation is linked to their parents’ “not too much” (18%) or “not at all” (33%).

Young adults are much more likely than middle-aged and older adults to see a strong connection between their financial situation and their parents’ financial situation. Among those ages 35 to 49 whose parents are still living, 31% say there is a great deal or some linkage between their financial situation and that of their parents. Among those ages 50 and older the share is slightly smaller (24%).

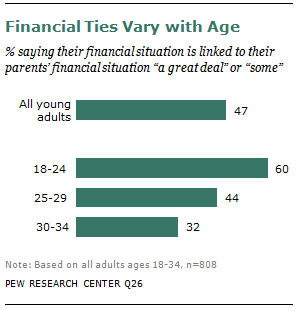

Among young adults themselves, the degree to which they perceive a link between their finances and their parents’ varies with age. For the youngest adults, the connection is the strongest. Fully 60% of 18- to 24-year-olds say their financial situation is linked to their parents’ a great deal or some. Among those ages 25 to 29, 44% say the same. For young adults in their early thirties, there is less likely to be a strong link between their finances and their parents’. A third (32%) say there is a great deal or some linkage between the two, while 66% describe it as not too much or not at all.

Among those adults who believe there is at least some connection between their financial situation and that of their parents, the vast majority see this as a good thing. Three-quarters (74%) say their parents’ financial situation has had a positive impact on their current financial situation. Only one-in-five say the impact has been negative.

This pattern holds true across age groups. Among 18- to 34-year-olds, as well as those ages 35 and older, most of those who see a connection between their financial situation and their parents’ say the impact on them has been positive.

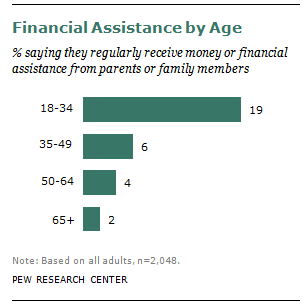

While many adults see a link between their finances and their parents’ finances, relatively few say they actually receive regular financial assistance from their parents. Overall, 9% of all adults say they receive money or financial assistance from their parents or other family members on a regular basis. Among adults ages 18 to 34, the share is considerably higher (19%). Among those ages 35 and older, only 4% say they receive this type of help.

Not surprisingly, the youngest adults are the most likely to rely on their parents for regular assistance. Fully a third (34%) of 18- to 24-year-olds say their parents regularly give them money or financial help. Among those ages 25 to 34, only 8% say the same.

The share of young adults receiving assistance from their parents or other family members does not differ by gender or race. Young adults who are working full time are among the least likely to say they receive regular assistance from their parents.