The U.S. economy employed nearly 156 million workers in 2018 in the midst of a record long spell of job creation. The jobs these workers did are different from what workers had done a few decades ago. Opportunities in the manufacturing sector have diminished, shrunken by a rising tide of automation and globalization. Meanwhile, the growing demand for a college education and the emergence of Millennials have fueled growth in the education sector. And the aging Baby Boomers have created an appetite for more health care workers.

The U.S. economy employed nearly 156 million workers in 2018 in the midst of a record long spell of job creation. The jobs these workers did are different from what workers had done a few decades ago. Opportunities in the manufacturing sector have diminished, shrunken by a rising tide of automation and globalization. Meanwhile, the growing demand for a college education and the emergence of Millennials have fueled growth in the education sector. And the aging Baby Boomers have created an appetite for more health care workers.

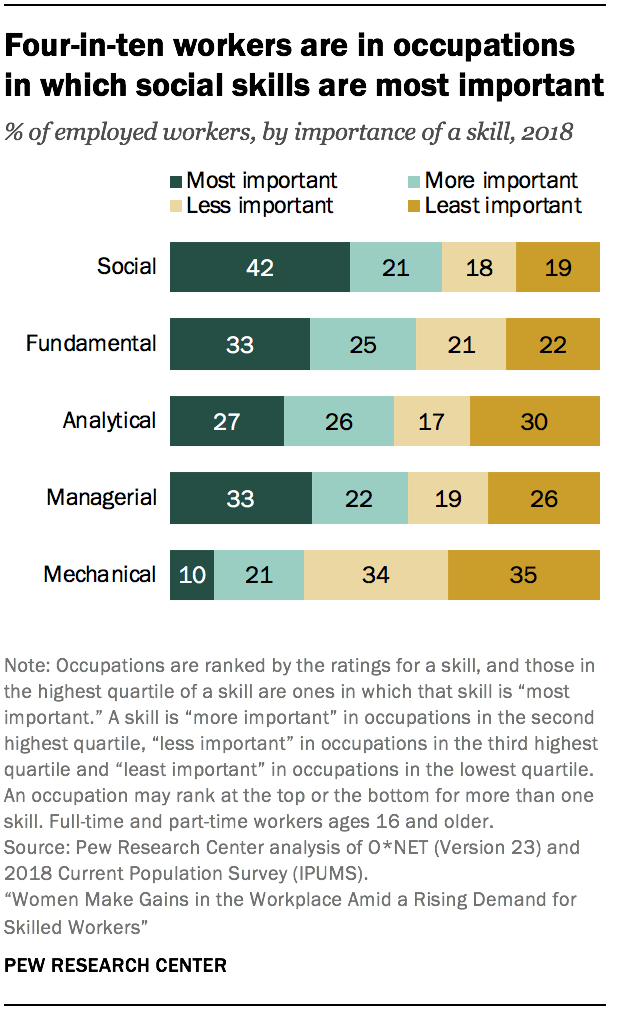

Viewed through the lens of skills, a sizable plurality of workers are engaged in occupations in which socials skills are most important, such as nursing and retail sales. In 2018, 42% of all workers, or 65 million, held jobs in which social skills are most important. In contrast, only 19% of workers were employed in occupations in which social skills are least important.

Fundamental skills are also in relatively high demand. Some 33% of workers were employed in occupations in which fundamental skills are most important, such as accounting and teaching, compared with 22% in occupations in which fundamental skills are least important. The need for managerial skills is similar, with 33% of workers in jobs in which managerial skills are most important and 26% in jobs in which they are least important.

The demand for analytical skills is more diffuse, perhaps because they represent a more specialized set of science, engineering and technological skills. While about one-in-four workers are employed in occupations in which analytical skills are most important, nearly one-in-three are in occupations in which analytical skills are least important. The need for workers who possess mechanical skills is modest – only 10% are employed in occupations in which mechanical skills are most important.

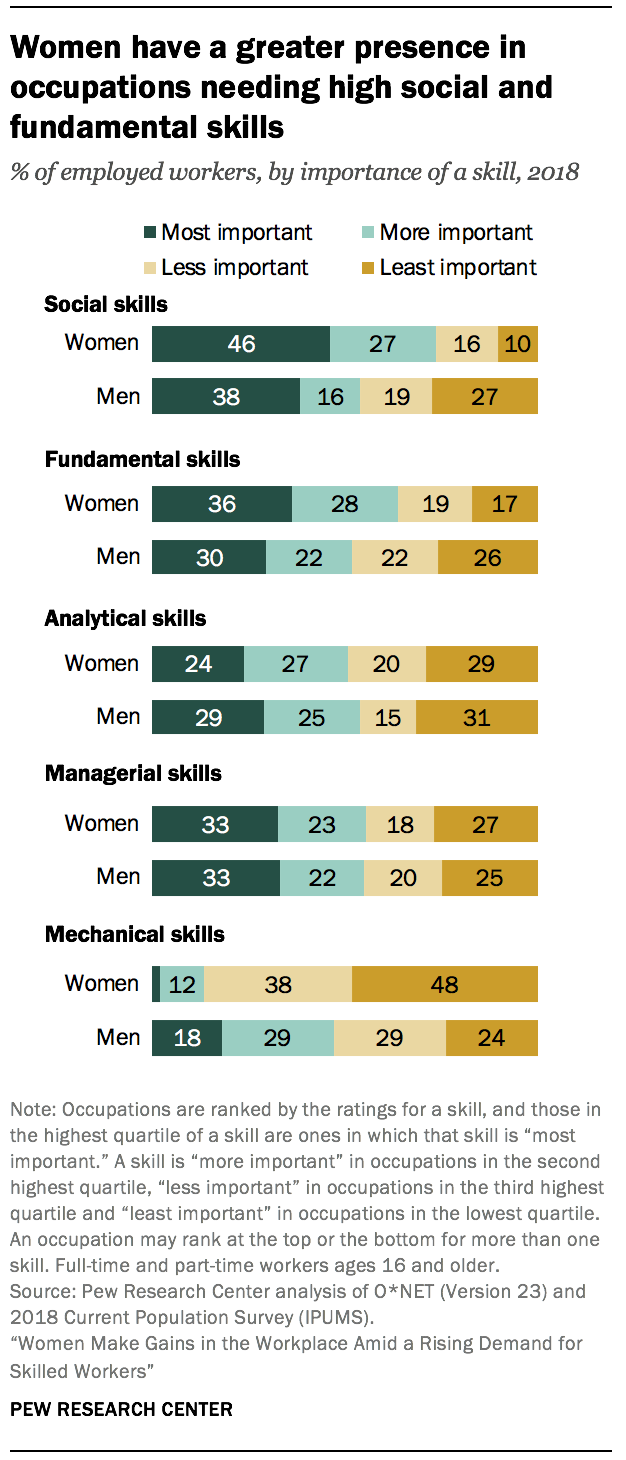

Women are more likely than men to hold jobs that require a high degree of proficiency in social skills. In 2018, nearly three-in-four women either worked in occupations in which social skills are most important (46%) or more important (27%). Among men, about half worked in jobs in which social skills are most important (38%) or more important (16%). Men were nearly three times as likely as women to hold jobs where social skills are least important, 27% vs. 10%.

Women are more likely than men to hold jobs that require a high degree of proficiency in social skills. In 2018, nearly three-in-four women either worked in occupations in which social skills are most important (46%) or more important (27%). Among men, about half worked in jobs in which social skills are most important (38%) or more important (16%). Men were nearly three times as likely as women to hold jobs where social skills are least important, 27% vs. 10%.

On the other hand, men are much more likely than women to work in jobs requiring mechanical skills. In 2018, 47% of men were employed in occupations in which these skills are either most or more important, compared with only 14% of women. Conversely, women were twice as likely as men – 48% vs. 24% – to be found in jobs in which mechanical skills are least important.

Women also have an edge over men with respect to fundamental skills. About two-thirds of women (64%) were in jobs in which fundamental skills are either most or more important, compared with 52% of men. The gender gap in analytical skills is narrow, with women and men almost equally spread across jobs ranked by the importance of analytical skills.

There is virtually no difference in how women and men are represented in occupations grouped by the importance of managerial skills.

The differences in the skill distributions of women and men have implications for their earnings. As shown in the next chapter, wages increase with the importance ratings of nonmechanical skills and decrease with the importance rating of mechanical skills. With women placed more favorably in the realm of nonmechanical skills and men leaning more to mechanical skills, the differences in employment patterns boost women’s earnings and help narrow the gender wage gap.

Occupations often need higher proficiency in more than one skill

A key aspect of workplace skills is that jobs often place a high degree of emphasis on more than one skill. In general, social, fundamental, analytical and managerial skills operate in harmony, a higher need for one skill accompanied by a higher need for the other skills. However, mechanical skills are weakly, and negatively, related with the other skills. Thus, there is considerable overlap in the counts of workers in jobs in which social, fundamental, analytical and managerial skills are more (or less) important, but there is little overlap among jobs in which mechanical skills and other skills are more important.

The relationship among skills is illustrated by the appearance of some occupations at the top of the ratings of more than one skill. For example, education administrators are called upon to be highly adept in social, fundamental and managerial skills. The 10 occupations that appear at the top of the importance ratings for each skill in 2018 are as follows:

Social skills – Coaches and scouts; educational, guidance, school and vocational counselors; clergy; lodging managers; sales managers; education administrators, elementary and secondary school; marriage and family therapists; emergency management directors; education administrators, preschool and child care center/program; and first-line supervisors of office and administrative support workers.

Fundamental skills – Neuropsychologists and clinical neuropsychologists; education administrators, elementary and secondary school; psychiatrists; judges, magistrate judges and magistrates; lawyers; physics teachers, postsecondary; agricultural sciences teachers, postsecondary; clergy; law teachers, postsecondary; and anthropology and archeology teachers, postsecondary.

Analytical skills – Biomedical engineers; physicists; chemical engineers; aerospace engineers; nuclear engineers; software developers, applications; operations research analysts; computer and information research scientists; remote sensing scientists and technologists; and mining and geological engineers, including mining safety engineers.

Managerial skills – Education administrators, elementary and secondary school; construction managers; medical and health services managers; chief executives; training and development managers; purchasing managers; education administrators, postsecondary; education administrators, preschool and child care center/program; lodging managers; and first-line supervisors of non-retail sales workers.

Mechanical skills – Signal and track switch repairers; heating and air conditioning mechanics and installers; aircraft mechanics and service technicians; elevator installers and repairers; electric motor, power tool and related repairers; industrial machinery mechanics; mobile heavy equipment mechanics, except engines; electromechanical technicians; millwrights; and electrical and electronics repairers, commercial and industrial equipment.

Simple correlations show that the strongest complementarity is among fundamental and social skills. The correlation between the ratings for these two skills in 2018 was 0.83, on a scale of zero (not related) to one (perfectly related). Other notable correlations are between fundamental and analytical skills (0.76), social and managerial skills (0.67), and fundamental and managerial skills (0.61). A principal components analysis finds that mechanical skills comprise one principal component, and the remaining skills comprise the second principal component, affirming the complementarity of nonmechanical skills and their independence from mechanical skills.

Gender differences in skills are rooted in gender differences in occupations

The skills that women and men deploy in the workplace are influenced by the specific occupations they gravitate to, whether by choice or by dint of cultural norms and other constraints.

The skills that women and men deploy in the workplace are influenced by the specific occupations they gravitate to, whether by choice or by dint of cultural norms and other constraints.

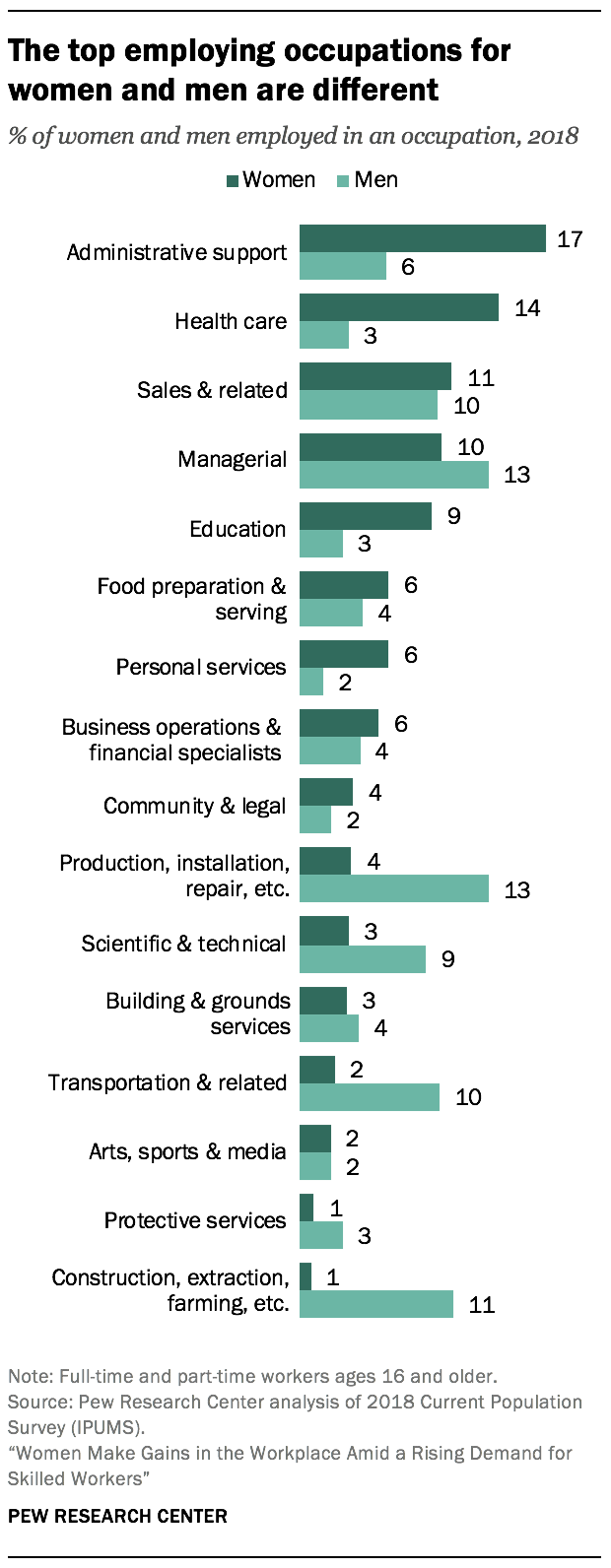

The occupations in which women are more concentrated are often represented at the top of the ratings of social, fundamental and managerial skills. They fall into the broad categories of administrative support, health care, sales and related, managerial, and education related occupations. Collectively, these five major groups of occupations accounted for 61% of women’s employment in 2018. Examples of these types of jobs include supervisors of administrative support workers, psychiatrists, supervisors of sales workers, medical and health services managers, and education administrators (see text box).

In contrast, men are more concentrated in jobs with a stronger need for mechanical skills. Specifically, production, installation and repair occupations, construction, extraction and farming, and transportation and related occupations are among the top five occupations for men, accounting for 34% of their employment in 2018. Examples of jobs within these broad groups include signal and track switch repairers, elevator installers and repairs, and industrial machinery mechanics.

Employment is rising rapidly in jobs in which social and fundamental skills are most important

The value placed on social and fundamental skills in the modern workplace reflects the rapid growth in employment in jobs in which these skills are most important, by 111% and 104% from 1980 to 2018, respectively. Jobs in which analytical skills are most important expanded nearly as much, rising in employment by 92%. The pace of hiring in these jobs was well in excess of the gain in employment overall (58%).

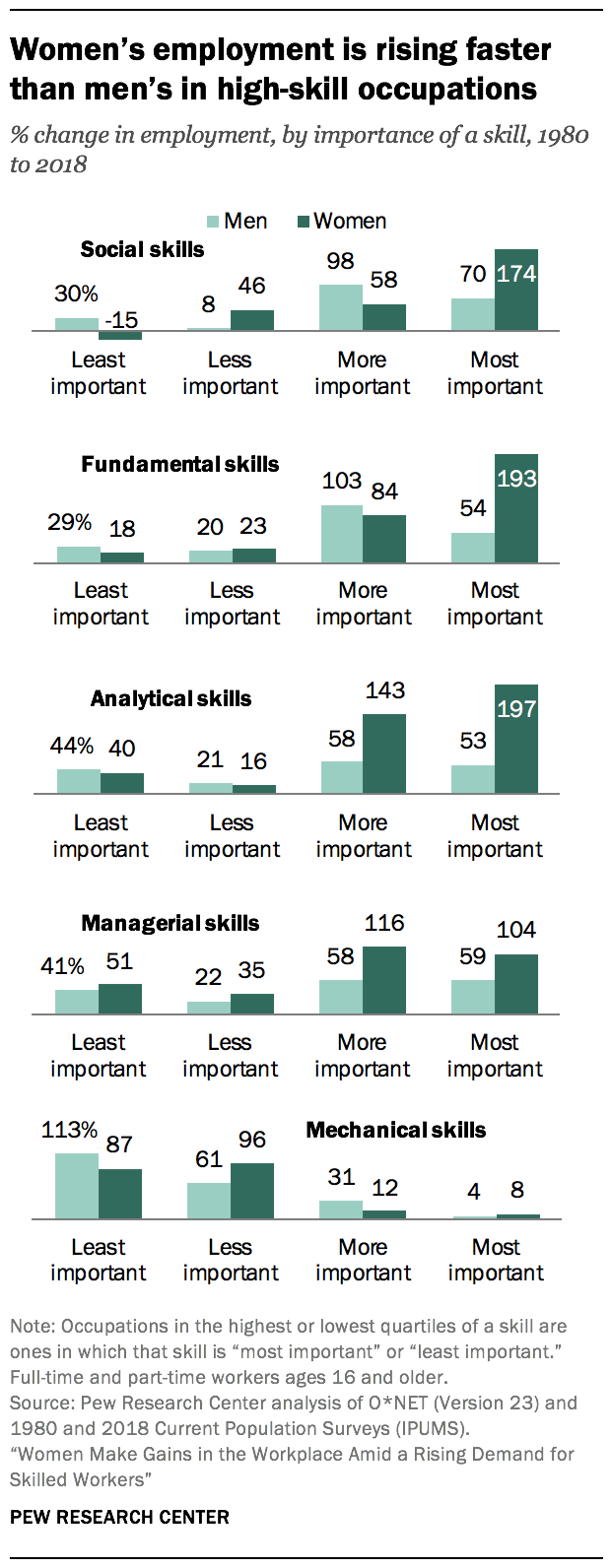

Women have done more than men to capitalize on the increased demand for social, fundamental and analytical skills.15 The employment of women in jobs in which social skills are most important increased 174% from 1980 to 2018, compared with 70% for men. An even greater gender divide appeared during this time in hiring into jobs in which fundamental skills are most important – 193% to 54% in favor of women. Women’s gains in employment (197%) also outdistanced men’s (53%) in occupations relying most on analytical skills. Overall, women’s employment increased by 74% from 1980 to 2018, compared with 45% for men.

Women have done more than men to capitalize on the increased demand for social, fundamental and analytical skills.15 The employment of women in jobs in which social skills are most important increased 174% from 1980 to 2018, compared with 70% for men. An even greater gender divide appeared during this time in hiring into jobs in which fundamental skills are most important – 193% to 54% in favor of women. Women’s gains in employment (197%) also outdistanced men’s (53%) in occupations relying most on analytical skills. Overall, women’s employment increased by 74% from 1980 to 2018, compared with 45% for men.

In contrast, men were more inclined than women to move into jobs in which social, fundamental and analytical skills are least important. For example, among jobs in which social skills are least important, men’s employment increased 30% from 1980 to 2018, compared with a decrease of 15% in women’s employment.

As social, fundamental and analytical skills have become more prominent in the workplace, the importance of mechanical skills has diminished sharply. Occupations in which mechanical skills are most important barely registered an increase in employment from 1980 to 2018 – only 8% for women and 4% for men, compared with the 58% increase in employment overall.

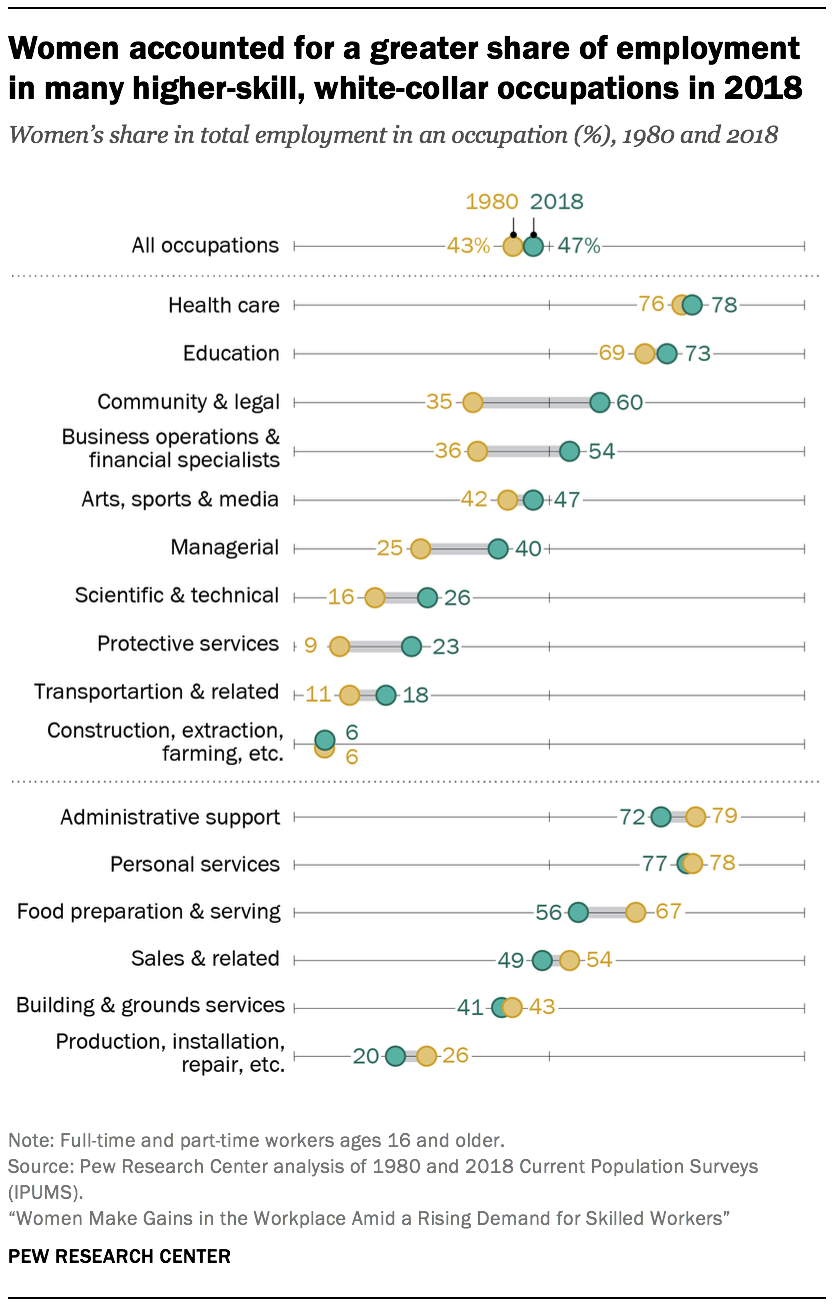

The rapidly growing presence of women in higher-skill nonmechanical activities is partly a result of their transition into new lines of work since 1980. Most notably, women’s share in employment in community and legal services occupations increased from 35% in 1980 to 60% in 2018. Women also moved into the majority in business operations and financial specialist occupations, with their share in employment increasing from 36% to 54% over the period. Other notable changes include the rising presence of women in managerial as well as scientific and technical occupations, with their shares in these two job categories increasing by 15 and 10 percentage points, respectively.

On the other side of the ledger, women pivoted away from food preparation and serving, administrative support, and installation, maintenance and repair occupations from 1980 to 2018. The most significant change was the exit from food preparation and serving occupations, with women’s share in employment in these jobs decreasing from 67% to 56% over the period. Meanwhile, women’s share in employment in administrative support occupations fell from 79% to 72%, and their share in installation, maintenance and repair occupations decreased from 26% to 20%.

On the other side of the ledger, women pivoted away from food preparation and serving, administrative support, and installation, maintenance and repair occupations from 1980 to 2018. The most significant change was the exit from food preparation and serving occupations, with women’s share in employment in these jobs decreasing from 67% to 56% over the period. Meanwhile, women’s share in employment in administrative support occupations fell from 79% to 72%, and their share in installation, maintenance and repair occupations decreased from 26% to 20%.

The occupations that women progressed into from 1980 to 2018 require higher degrees of proficiency in nonmechanical skills than the occupations women retreated from. For example, the average rating for fundamental skills in community and legal services occupations was 3.7 in 2018 (on the O*NET scale from one to five, or from “not important” to “extremely important”). The average rating for fundamental skills in food preparation and serving occupations was 2.7.

Overall, the occupational transitions made by women from 1980 to 2018 are one reason why their employment in higher-skill nonmechanical occupations has grown more rapidly than the employment of men in similar occupations. Nonetheless, as noted above, these shifts fell short of closing the gender gap in the occupational distributions of men and women. While women accounted for 47% of employment overall in 2018, their shares were markedly higher than this in health care, education, administrative support and personal services occupations and distinctly lower in some higher-skilled occupations, such as scientific and technical occupations.

Overall, the occupational transitions made by women from 1980 to 2018 are one reason why their employment in higher-skill nonmechanical occupations has grown more rapidly than the employment of men in similar occupations. Nonetheless, as noted above, these shifts fell short of closing the gender gap in the occupational distributions of men and women. While women accounted for 47% of employment overall in 2018, their shares were markedly higher than this in health care, education, administrative support and personal services occupations and distinctly lower in some higher-skilled occupations, such as scientific and technical occupations.

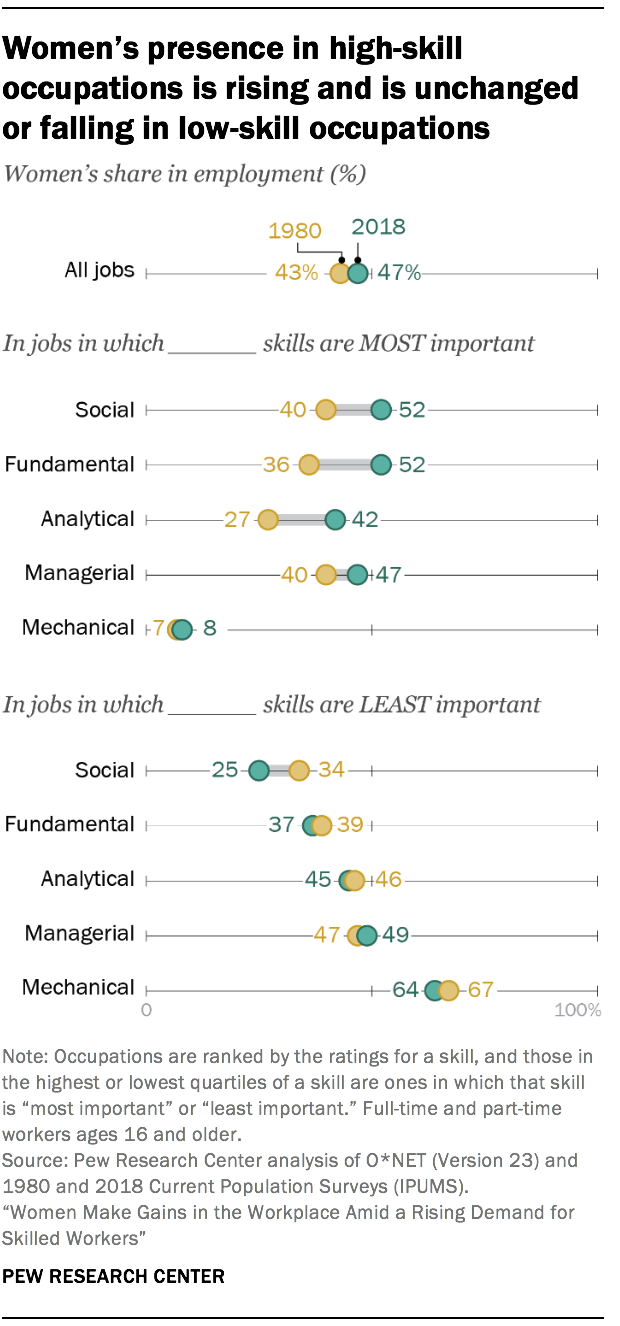

The occupational gender gap notwithstanding, the profile of women in high-skill jobs has come into sharper relief since 1980. As noted, women’s share of employment in jobs in which social, fundamental and analytical skills are most important increased rapidly from 1980 to 2018. Meanwhile, women’s role in occupations placing the least importance on social skills has diminished markedly, from 34% in 198o to 25% in 2018. Their presence in occupations least in need of fundamental, analytical, managerial or mechanical skills is largely unchanged.

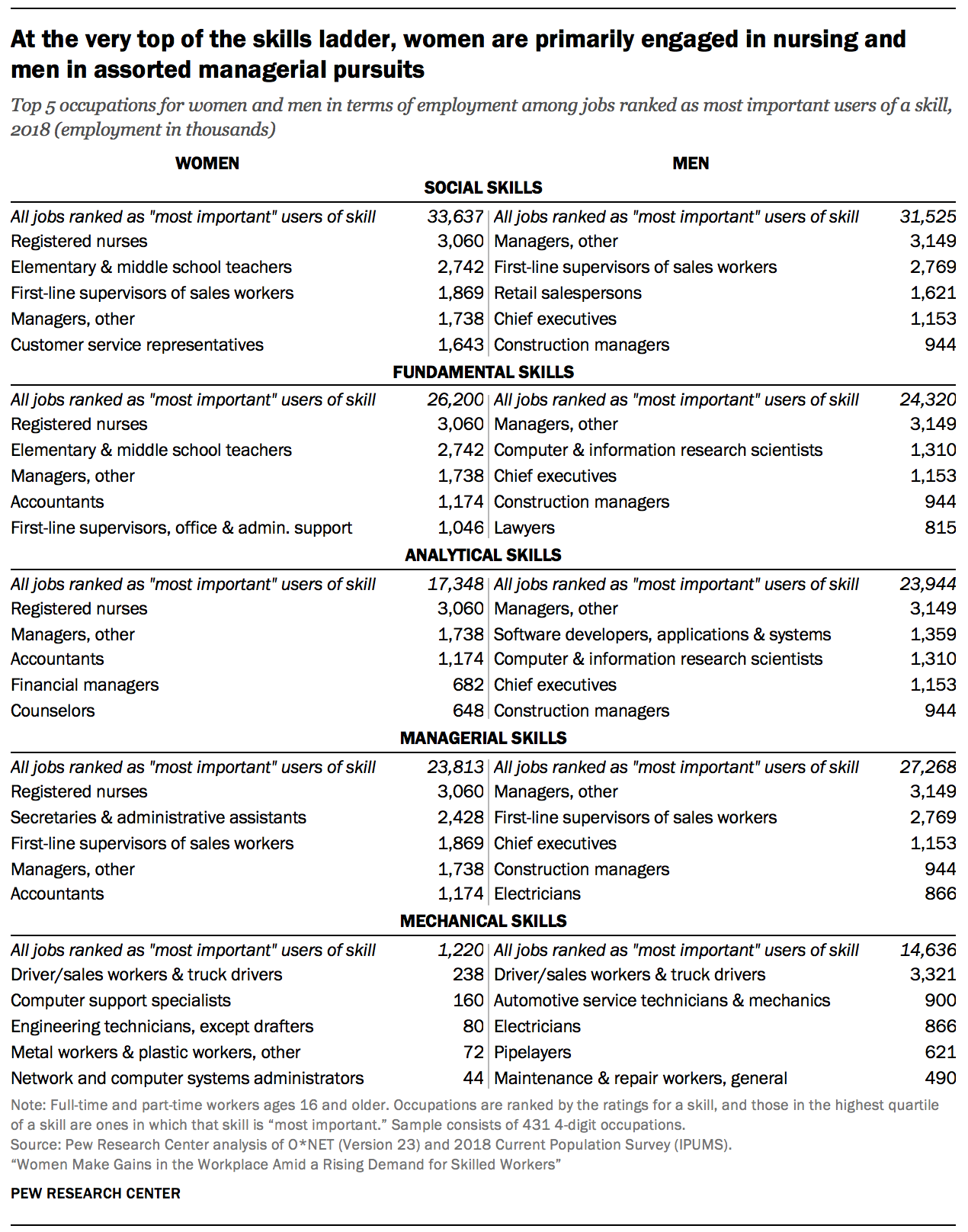

At the top of the skills ladder, nursing is a leading activity for women and management is a leading activity for men

Occupations ranked at the top of the social skills ladder employed nearly 34 million women and 32 million men in 2018. In terms of employment, the leading high-social-skills job for women was nursing, with 3 million women working as registered nurses in 2018. Employment as elementary and middle school teachers was nearly as important for women in the group of occupations requiring high social skills, followed by supervising sales workers, managing in assorted jobs and providing customer service. Notably, vast majorities of registered nurses (88%) and elementary and middle school teachers (80%) are women.

For men, a variety of managerial jobs provided the top high-social-skills opportunities, engaging more than 3 million men in 2018. Perhaps not surprisingly, most such managers (64%) are men. Retail sector jobs were also significant as a leading social skills activity, with more than 4 million men managing sales workers or working as retail salespersons.

Across other nonmechanical skills, nursing also emerges as a key occupation for women serving in top-rung fundamental, analytical and managerial skills jobs. So too are miscellaneous managerial jobs, even though women account for only about one-third of employment in these jobs. Retail jobs in supervisory capacities and accounting are other key high-skill occupations for women.

Men in jobs calling for prowess in fundamental, analytical and managerial skills are principally employed as managers, from serving as chief executives to construction managers to an assortment of other managerial jobs. Most construction managers (92%) and chief executives (73%) are male. So too are computer research and software developers, other major sources of high-skill work for men.