Most Asian Americans feel good about their lives in the U.S. They see themselves as having achieved economic prosperity on the strength of hard work, a character trait they say is much more prevalent among Asian Americans than among the rest of the U.S. population. Most say they are better off than their parents were at a comparable age. And among the foreign born, very few say that if they had to do it all over again, they would stay in their home country rather than emigrate to the U.S.

As is customary for an immigrant group, their sense of identity in their new country is evolving. Roughly three-in-four adult Asian Americans were born outside of the U.S.; among this group, 60% say they see themselves as “very different” from the typical American. However, among Asian Americans who were born in the U.S., the pattern reverses: Roughly two-thirds (65%) say they consider themselves to be typical Americans.

Meanwhile, the “Asian American” label has not been embraced by any group of U.S. Asians, be they native born or foreign born. Most describe themselves by their country of origin, such as “Chinese American,” “Filipino American” or “Indian American,” rather than by a pan-Asian label. Overall, just one-in-five (19%) say they most often describe themselves as Asian or Asian American and even fewer (14%) say they describe themselves as just plain American.

This section examines how satisfied Asian Americans are with their lives—both personal and financial—and the extent to which they value hard work. It also looks at the topics of identity, language and assimilation. And it explores similarities and differences on these measures among the six major U.S. Asian groups.

Upward Mobility, Widespread Satisfaction

More than eight-in-ten Asian Americans (82%) say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their lives; only 13% are dissatisfied. When compared with the general public, Asian Americans are slightly more satisfied with their lives. In a July 2011 Pew Research survey, 75% of all American adults said they were satisfied with the way things were going in their lives.

There is little variance in this measure across gender, age and education attainment. And Asian Americans from the six major country of origin groups express roughly equal levels of satisfaction.

This high level of satisfaction may be tied in part to a shared experience of upward mobility. Nearly three-quarters of Asian Americans (73%) say they enjoy a better standard of living than their parents did at a comparable age. An additional 15% say their standard of living is about the same as that of their parents. Only one-in-ten say their standard of living is worse than their parents’ standard of living had been at a comparable age.

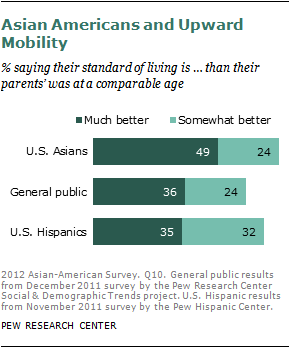

Moreover, about half of Asian Americans (49%) say their current standard of living is “much better” than their parents’ was at a comparable age. In this regard, Asian Americans are much more upbeat than the general public or Hispanics. In a 2011 Pew Research Center survey, only 36% of all American adults said their standard of living was much better than their parents’ standard of living had been at a comparable age. According to a 2011 Pew Hispanic Center survey, among Hispanics—the other major group of recent immigrants—a similar share (35%) said their standard of living was much better than their parents’ had been.

Asian immigrants are somewhat more likely than U.S.-born Asians to say their standard of living exceeds that of their parents. Among all foreign-born Asian Americans, 52% say their standard of living is much better than their parents’ had been. This compares with 42% of U.S.-born Asians. There is no significant difference between the most recent immigrants and those who arrived in the U.S. before 2000. Among Japanese Americans, the pattern is different: Japanese immigrants are less likely than those born in the U.S. to say their standard of living is much better than their parents’ had been at their age.

Education is not strongly linked to assessments of upward mobility. Asian Americans who are college graduates and those with less education are equally likely to say their current standard of living is much better than their parents’ standard of living had been at a comparable age.

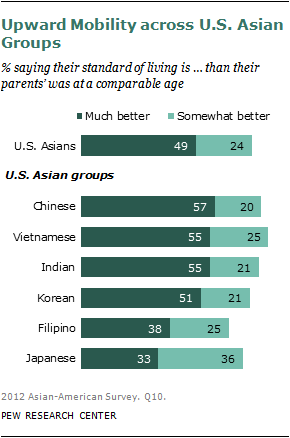

There is some variance in this measure across U.S. Asian groups. About half or more Americans of Chinese, Vietnamese, Indian and Korean origins say they enjoy a much better standard of living than their parents did at a comparable age. Japanese Americans and Filipino Americans are somewhat less likely to say that.

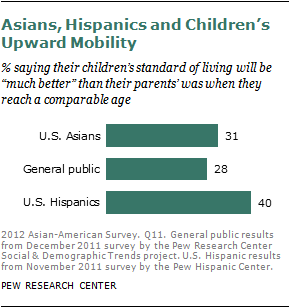

Respondents were also asked to predict how their children’s future standard of living will compare with their own. Overall, roughly half of all Asian Americans (53%) believe that when their children reach the age they are now, they will enjoy a better standard of living (31% say much better, 22% somewhat better). About one-in-five (19%) expect their children’s standard of living will be about the same as theirs is now. And the same share believes their children’s standard of living will be worse than theirs is now.

While Asian Americans are more likely than Hispanics to say their own standard of living exceeds that of their parents at a comparable age, Hispanics are more upbeat than Asian Americans about their children’s future well-being. Fully two-thirds of Hispanics (66%) believe their children will enjoy a better standard of living when they reach their parents’ age. Four-in-ten expect their children’s standard of living will be much better, and 26% believe it will be somewhat better. The general public is more in sync with Asian Americans on this measure—according to a December 2011 Pew Research survey, some 28% believe their children’s standard of living will be much better than theirs is.

On average, Hispanics have lower household incomes and lower educational attainment than do Asian Americans. In addition, their ratings of their current standard of living compared with their parents’ standard of living at a similar age are lower than those of Asians. When it comes to the future, however, expectations tend to have an inverse relationship to socio-economic status—meaning that those at the lower end of the income and educational ladder have higher expectations for their children’s futures relative to their own current circumstances.

Among Asian Americans, immigrants are somewhat more likely than those who were born in the U.S. to say their children will enjoy a much better standard of living than their parents currently do (34% vs. 20%).

In addition, there is some variance on this measure across socio-economic groups. Asian Americans without a college degree are somewhat more likely than those who have graduated from college to say they expect their children to have a much higher standard of living than they currently do (37% vs. 26%). In addition, Asian Americans with annual household incomes of less than $30,000 are more likely than middle-income and upper-income Asians to say their children will have a much higher standard of living (42% of those making less than $30,000 a year vs. 29% of those making between $30,000 and $74,999 and 24% of those making $75,000 or more).

Among the U.S. Asian groups, Vietnamese Americans are the most upbeat about their children’s futures. Fully 48% believe their children’s standard of living will be much better than theirs is when their children reach a comparable age. Vietnamese Americans’ attitudes about their children’s futures may be tied in part to their own socio-economic standing. Of the six major Asian-Americans groups, Vietnamese are the least likely to have a college degree, and, aside from Korean Americans, they have the lowest median annual household income. Americans of Japanese, Filipino and Chinese origins are among the least likely to say their children will enjoy a much better standard of living (19%, 25% and 26%, respectively). Among Korean Americans, 38% believe their children will be better off; among Indian Americans, 32% say the same.

Asian Americans Prospering in the U.S.

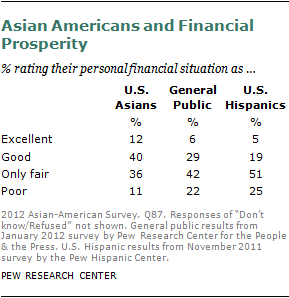

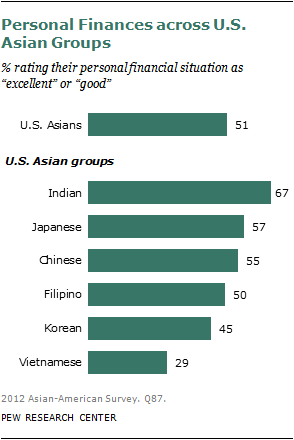

Even in these tough economic times, Asian Americans are relatively satisfied with their own personal financial situations. When asked whether they are in excellent shape, good shape, only fair shape or poor shape financially, about half of all Asian Americans say they are in excellent (12%) or good (40%) shape. Slightly less than half say they are in only fair (36%) or poor (11%) shape.

Overall, Asian Americans have a much more positive outlook on their personal finances than the general public or Hispanics. Only 35% of all American adults say they are in excellent or good shape financially, and an even smaller share of Hispanics (24%) say the same.

Asian Americans’ upbeat assessment of their personal finances is most likely linked to their overall affluence. As a group, Asian Americans have a significantly higher median annual income than all American adults. According to data from the Census Bureau’s 2010 American Community Survey (ACS), the median household income for all Asian Americans in 2010 was $68,000. This compares with $50,000 for all adults, regardless of race or ethnicity. In addition, Asian Americans have a lower unemployment rate than members of the general public.

Among Asian Americans, those who were born in the U.S. are only slightly more likely than those born outside of the U.S. to describe their personal financial situation as excellent or good (56% vs. 50%). This is a sharp contrast to the pattern seen among Hispanics. According to a 2011 Pew Hispanic Center survey, U.S.-born Hispanics are nearly twice as likely as the foreign born to say their finances are in excellent or good shape (33% vs. 17%). Among foreign-born Hispanics, fully 83% describe their personal financial situation as only fair or poor.46

Personal financial ratings vary widely across U.S. Asian groups. Indian Americans are the most likely to describe their personal financial situation as excellent or good (67%). Indian Americans also have the highest median income of the six largest U.S. Asian groups. Among Japanese Americans and Chinese Americans, more than half say their finances are in excellent or good shape (57% of Japanese and 55% of Chinese). Korean Americans are somewhat less likely to rate their finances as excellent or good (45%). Half of Filipino Americans rate their finances as excellent or good. Vietnamese Americans are the least likely to do so (29%).

Who’s Hardworking?

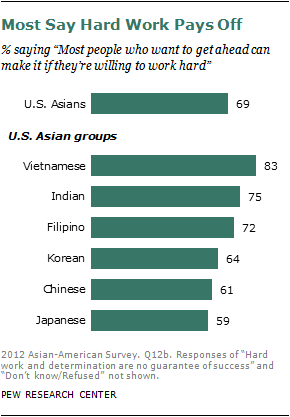

In general Americans tend to value hard work and believe that it can lead to success. Asian Americans are no exception. In fact, they appear to be even bigger proponents of hard work when compared with all American adults. The survey asked respondents which of the following two statements came closer to their view: Most people who want to get ahead can make it if they’re willing to work hard, or hard work and determination are no guarantee of success for most people. Roughly two-thirds of Asian Americans (69%) chose the first statement (most people can get ahead if they’re willing to work hard), while 27% chose the second statement (hard work is no guarantee of success).

The general public also leans toward the first statement, but by a somewhat less decisive margin. Among all American adults, 58% agree that most people who want to get ahead can make it if they’re willing to work hard, while 40% say hard work is no guarantee of success. For their part, Hispanics come closer to Asian Americans in this regard. Three-in-four Hispanics say most people can get ahead with hard work; 21% say hard work doesn’t guarantee success.

While solid majorities of each of the U.S. Asian groups agree that hard work pays off, there is some variation across groups. Vietnamese Americans are the most likely to agree that most people can get ahead if they work hard (83%). Americans of Japanese, Chinese and Korean origins are somewhat less likely to agree.

Overall, there is no significant gap in views on hard work between native-born and foreign-born Asian Americans. However, Japanese Americans born in the U.S. are much more likely than those born overseas to say hard work pays off.

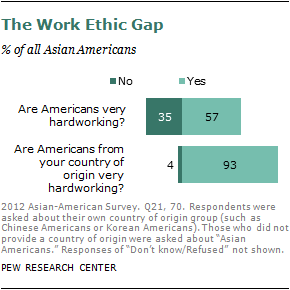

Perhaps more interesting than Asian Americans’ views on the value of hard work are their views about who is hardworking. Asian-American survey respondents were asked whether Americans in general are very hardworking and whether people from their own country of origin are very hardworking. To avoid having respondents make a direct comparison between Americans in general and their own native or ancestral group, one question was asked near the beginning of the survey, and the other question was asked near the end of the survey.

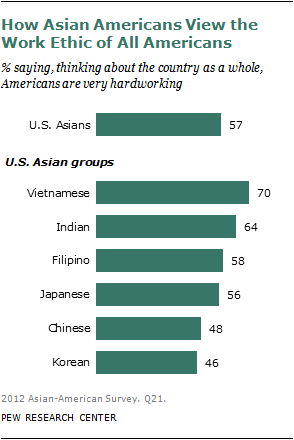

On balance, most Asian Americans see Americans in general as hardworking. Thinking about the country as a whole, some 57% say they would describe Americans as very hardworking; 35% say they would not describe Americans this way.

However, Asian Americans’ views about their own group’s work ethic are dramatically different. Respondents were asked whether they would describe their own ethnic group or country of origin group as very hardworking. For example, Chinese Americans were asked how they would describe Chinese Americans, and Filipino Americans were asked how they would describe Filipino Americans.47 Overall, 93% of Asian Americans said they would describe their own group as very hardworking. Only 4% said they would not describe their own group this way.

Findings on this measure are very consistent across the U.S. Asian groups. Majorities of roughly 90% or more of the six major Asian groups say their individual group is very hardworking (97% of Vietnamese say this).

There is more variance in views about how hardworking most Americans are. Korean Americans and Chinese Americans are the least likely to say that Americans in general are very hardworking (46% of Koreans and 48% of Chinese). Vietnamese Americans and Indian Americans are among the most likely to say Americans in general are very hardworking (70% of Vietnamese and 64% of Indians).

Are Asian Americans a “Model Minority”?

As a group, Asian Americans have sometimes been described as a “model minority.” The term, first used by sociologist William Petersen in a 1966 New York Times Magazine article to describe Japanese Americans, implies that Asian Americans have been more successful than other racial or ethnic minority groups in the U.S.48 This perception is based in part on demographic indicators such as educational attainment and income, and in part on perceptions about Asians’ values and work ethic.

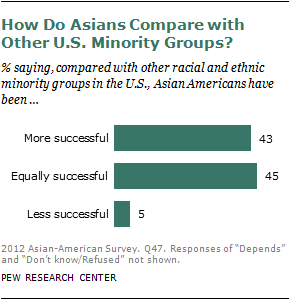

However, there is no clear consensus among Asian Americans regarding how they measure up to other minority groups. Some 45% say that Asian Americans, when compared with other racial and ethnic minority groups, have been about equally successful. Roughly the same share (43%) say Asian Americans have been more successful than other minority groups. Very few (5%) say Asian Americans have been less successful.

Opinion about the relative success of Asian Americans varies somewhat by age. Among young Asian-American adults (ages 18 to 34), 51% say as a group Asian Americans have been about as successful as other minority groups, while 37% say they have been more successful. By contrast, those ages 35 and older are more evenly divided on the issue: 47% say Asian Americans have been more successful than other minority groups, while 42% say Asian Americans have been equally successful.

Asian Americans with a higher annual household income are somewhat more likely than others to say, on the whole, that Asian Americans have been more successful than other minority groups in the U.S. Among those with incomes of $75,000 or higher, 53% say Asian Americans have been more successful than other groups. This compares with 39% of those with annual incomes of less than $75,000.

U.S.-born and foreign-born Asian Americans do not differ significantly in their views on this issue. Among the native born, 48% say Asian Americans have been about equally successful as other minority groups, while 40% say they have been more successful. Among Asian immigrants, 45% say Asian Americans have been equally successful, and 44% say they have been more successful.

However, when the foreign-born group is divided into those who arrived in the U.S. in the past 12 years and those who came to the U.S. before 2000, significant differences emerge. Newer immigrants to the U.S. tend to think Asian Americans are just as successful as other minority groups (51%) rather than more successful (36%). Immigrants who arrived in the U.S. before 2000 are more inclined to say Asian Americans have had greater success in the U.S. than other minority groups (48%), than they are to say Asian Americans have been equally successful (42%).

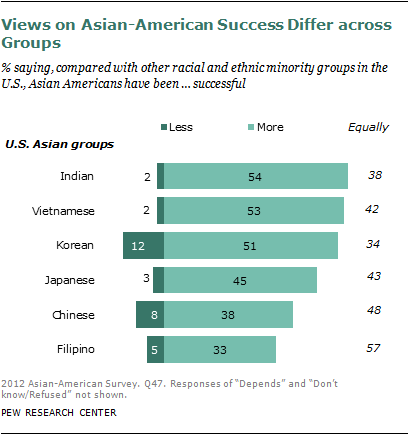

In addition, there are significant differences of opinion across U.S. Asian groups. Indian Americans and Vietnamese Americans are among the most likely to say Asian Americans have been more successful than other U.S. minority groups. Chinese Americans and Filipino Americans are among the least likely to express this view. Among Filipino Americans, 57% say Asian Americans have been about as successful as other minority groups (the highest share among the six U.S. Asian groups).

Korean Americans (12%) are more likely than other Asian Americans to say Asians have been less successful than other minority groups in the U.S. Japanese Americans are evenly divided over how successful Asian Americans have been: 45% say they have been more successful than other minority groups, and a similar share (43%) say they have been about as successful as other minority groups.

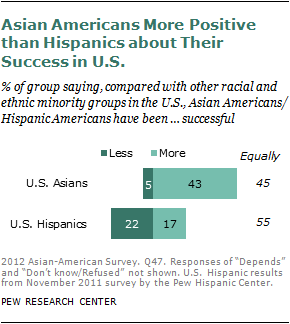

The Asian-American immigrant experience has been different in many ways from the experience of Hispanic Americans. As the demographic data illustrate, Hispanics overall have struggled more than Asians economically, and they lag behind in terms of educational attainment. In addition, a larger share of Hispanic immigrants are in the U.S. illegally. When Hispanics themselves are asked to evaluate their success relative to other racial and minority groups in the U.S., they paint a much less positive picture than do Asian Americans.

In a 2011 Pew Hispanic Center survey of Hispanic Americans nationwide, a narrow majority (55%) said, compared with other U.S. minority groups, Hispanics have been about equally successful. However, only 17% said they have been more successful than other minority groups (compared with 43% of Asian Americans). And 22% of Hispanics said, as a group they have been less successful than other minorities (compared with only 5% of Asian Americans).

How Do Asian Americans Describe Themselves?

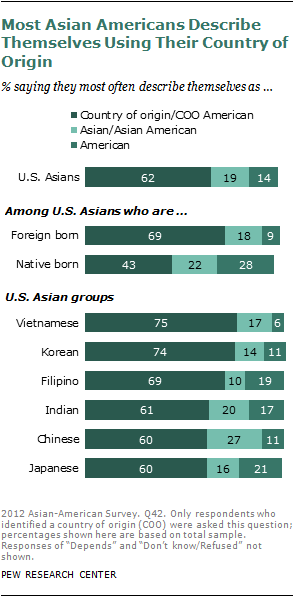

The U.S. Census Bureau defines “Asian” as “having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.”49 This is a broad definition and encompasses groups with vastly different backgrounds—geographically, culturally and linguistically. Asian Americans are much more likely to identify themselves by their country of origin than by the broader label of Asian American.

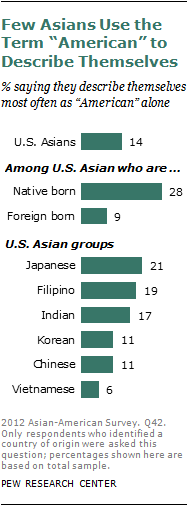

Overall, 62% of Asian Americans say they most often describe themselves by using the country where they or their family originated (e.g., Chinese or Chinese American). One-in-five (19%) most often describe themselves as Asian or Asian American, and 14% most often describe themselves as American.50

There is broad consistency across U.S. Asian groups on this measure. Majorities of each group say they describe themselves most often using their country of origin. Americans of Vietnamese, Korean and Filipino origins are more likely than other Asians to use their country of origin most often when describing themselves. Chinese Americans are slightly more likely than all other Asian Americans to say they describe themselves as Asian or Asian American (27% vs. 16% of all other Asian Americans).

The fact that so many Asian Americans identify with their home countries is not surprising, given that such a large share were born outside of the U.S. Among foreign-born Asian Americans, fully 69% say they describe themselves most often using a term that incorporates the country from which they emigrated, as in Korean American or Indian American.

Some 18% of foreign-born Asian Americans describe themselves using the Asian or Asian American label. Only 9% describe themselves most often as American. There is little difference in this regard between newer immigrants to the U.S. and those who arrived before 2000. Roughly seven-in-ten from each group say they most often describe themselves using the country from which they emigrated.

The pattern is much different among American-born Asian Americans. Fewer than half (43%) describe themselves most often using their ancestral country of origin, 22% describe themselves as Asian or Asian American, and 28% describe themselves as American. The identity gap between foreign-born and native-born Asian Americans can be seen within specific groups as well. For example, among Filipino Americans, 77% of the foreign born most often identify themselves as Filipino American, while only 51% of the native born identify themselves that way. Similarly among Chinese Americans, 67% of the foreign born most often identify themselves as Chinese American, compared with 35% of those born in the U.S.51

Among the U.S. Asian groups, Japanese Americans (21%) and Filipino Americans (19%) are the most likely to describe themselves simply as American. Vietnamese Americans are among the least likely to describe themselves that way (6%). For the other major U.S. Asian groups, between 11% and 17% describe themselves most often as American.

When Hispanic Americans were asked a question with similar wording, they too tended to identify more with their country of origin than with the broader “Hispanic” label. In the 2011 Pew Hispanic Center survey, 51% of Hispanic Americans said they most often describe themselves using their country of origin (e.g. Mexican or Salvadoran).52 Roughly a quarter (24%) said they describe themselves most often as Latino or Hispanic, and 21% said they describe themselves as American.

Typical American or Very Different?

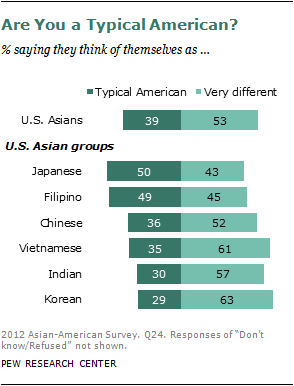

Asian Americans were asked if they think of themselves as a typical American or very different from a typical American. On balance, they are more likely to see themselves as very different (53%) than as typical (39%).

Views on this question are fairly consistent across major demographic variables. Both Asian-American men and women are more likely to see themselves as very different from the typical American than they are to see themselves as typical Americans. Similarly, young and old Asian Americans see themselves as more different than typical.

In addition, among Asian Americans who have a college degree and those who do not, about half say they see themselves as very different from the typical American, while about four-in-ten see themselves as a typical Americans. Opinion differs somewhat by income. Asian Americans with annual household incomes of less than $30,000 are more likely than middle- and high-income Asian Americans to say they see themselves as very different from the typical American (61%, compared with 50% of those with annual incomes of $30,000 or more).

Asian Americans who live in the West, the region with the highest concentration of Asians, are more likely than those living in other parts of the U.S. to think of themselves as typical Americans (44% vs. 34%). Still, 49% of Asian Americans living in the West say they are very different from typical Americans.

The extent to which Asian Americans feel like typical Americans varies across U.S. Asian groups. Japanese and Filipino Americans are more likely than Americans of Chinese, Vietnamese, Indian or Korean origins to say they think of themselves as typical Americans. About half of Japanese and Filipino Americans say they are typical Americans, compared with 36% or less of each of the other groups.

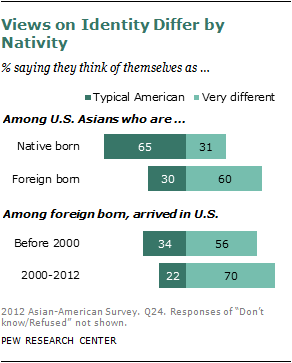

Whether an individual was born in the U.S. or outside of the U.S. is strongly linked to these attitudes. Native-born Asian Americans are much more likely than those who were born outside the U.S. to see themselves as typical Americans (65% vs. 30%).

This pattern holds across U.S. Asian groups as well. Among Japanese Americans, 70% of those born in the U.S. say they think of themselves as typical Americans. This compares with only 20% of Japanese immigrants. Similarly, among Chinese Americans, 66% of the native born consider themselves typical Americans, compared with 26% of the foreign born.

The most recent immigrants are among the least likely to say they see themselves this way. Among those who came to the U.S. between 2000 and 2012, only 22% say they see themselves as typical Americans (70% say they are very different from typical Americans). Among those who immigrated to the U.S. before 2000, 34% see themselves as typical Americans (56% very different).

Some of the group differences on this measure are most likely related to nativity. Indian Americans are among the least likely to see themselves as typical Americans, and they are among the most likely to be recent immigrants to the U.S. Fully one-third of the Indian Americans surveyed arrived in the U.S. within the past 12 years; only 11% were born in the U.S. At the other extreme, Japanese Americans are among the most likely to see themselves as typical Americans, and they are by far the most likely to have been born in the U.S. Roughly six-in-ten Japanese Americans surveyed were born in America; only 6% arrived in the U.S. in 2000 or later.

Overall, Asian Americans are somewhat less likely than Hispanics to see themselves as typical Americans (39% vs. 47%). However, this is likely due to the fact that more Asian Americans than Hispanics were born outside the U.S. After controlling for nativity, the responses of Asian Americans and Hispanics are quite similar. Among Hispanics who were born in the U.S., 66% see themselves as typical Americans. An almost identical share of U.S.-born Asian Americans (65%) say the same. Among Hispanics who were born outside of the U.S., only three-in-ten (31%) see themselves as typical Americans; 30% of foreign-born Asian Americans say the same.

The Importance of Language

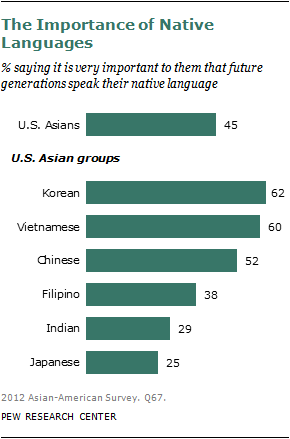

For most immigrants, an important part of assimilating to the U.S. is learning to speak English. Many immigrants must balance the need to adapt to the language and culture of the U.S. with their desire to maintain ties to their native country. A strong majority of Asian Americans (80%) say it is at least somewhat important to them that future generations of Asians living in the U.S. be able to speak their native or ancestral language. However, less than half (45%) say this is “very important,” and there is quite a bit of variation across U.S. Asian groups. In addition, relatively few U.S.-born Asian Americans are proficient in their ancestral language. Only 14% say they can carry on a conversation in that language very well.

In thinking about the importance of language preservation, respondents were asked specifically about future generations of Asians from their own country of origin. For example, Chinese Americans were asked how important it is to them that future generations of Chinese living in the U.S. be able to speak Chinese.53 The survey finds that maintaining ties to their native language is more important to Americans of Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese origins than it is to those of Filipino, Indian and Japanese origins.

Among Korean Americans, 62% say that it is very important to them that future generations of Koreans living in the U.S. speak Korean. Roughly the same proportion of Vietnamese Americans (60%) say it is very important to them that future generations speak Vietnamese. And 52% of Chinese Americans say it is very important that future generations speak Chinese.

The three remaining groups place less value on maintaining ties to their native language. Among Filipino Americans, only 38% say it is very important that future generations of Filipinos speak Tagalog or another Filipino language. While the Philippines became a sovereign country in 1946, U.S. control over the islands from 1898 to 1946 greatly influenced the way that language developed. Many Filipino Americans spoke English long before they came to the U.S. As a result, they may be less wedded to a native Filipino language.

Only three-in-ten Indian Americans (29%) say it is very important to them that future generation of Indians living in this country speak Hindi or another Indian language. There is a great diversity of languages spoken in India. Hindi is the principal official language, and English is a secondary official language. The Constitution of India recognizes more than 20 major languages. In addition, there are hundreds of dialects. Given this diversity of language, many Indians who immigrate to the U.S. may see limited utility in maintaining ties to a language that is not widely spoken in this country.

Among all U.S.-born Asian Americans, only 32% say it is very important to them that future generations speak their native tongue. By contrast, among foreign-born Asian Americans, 49% say this is very important to them. Japanese Americans are among the least likely to place a high level of importance on keeping the Japanese language alive in the U.S. Only one-in-four say it is very important to them that future generations of Japanese living in the U.S. be able to speak Japanese. This may be related in part to the fact that relatively few Japanese Americans were born outside of the U.S. (32%).

Mastering English and Keeping Native Languages Alive

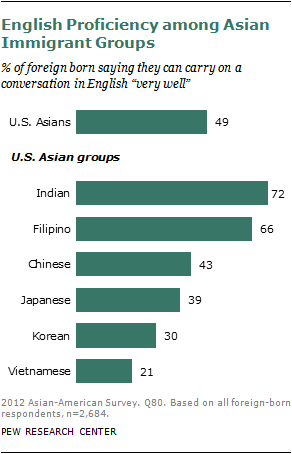

Foreign-born survey respondents were asked to assess their own English proficiency. Half of all foreign-born Asian Americans (49%) say they can carry on a conversation in English “very well”—both understanding and speaking. Some 26% say they can do this pretty well. An additional 25% can do this just a little or not at all. Not surprisingly, immigrants who arrived in the U.S. more recently are less proficient in English. Among those who emigrated within the past 12 years, only 39% say they can carry on a conversation in English very well. This compares with 52% who came to the U.S. before 2000.

The American Community Survey includes a question about English proficiency for all Asian Americans, whether native born or foreign born. According to the 2010 ACS, 53% of foreign-born Asian Americans either speak only English at home or speak another language at home but say they speak English “very well.”

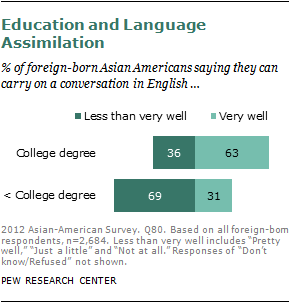

Among the Pew Research survey respondents, older foreign-born Asian Americans are somewhat less likely than their younger counterparts to be proficient in English. Among those ages 55 and older, 35% say they can carry on a conversation in English very well. This compares with 56% of those under age 55. There is a large education gap as well. More than six-in-ten Asian-American immigrants (63%) who have graduated from college say they can carry on a conversation in English very well, compared with only 31% of those with less education.

Among the foreign born, there is wide variation across U.S. Asian groups. Immigrants from India and the Philippines—both countries where English is widely spoken—give themselves the highest marks for their ability to converse in English. Roughly seven-in-ten foreign-born Indian Americans (72%) say they can carry on a conversation in English very well, as do 66% of foreign-born Filipinos.

Chinese, Japanese and Korean immigrants are less likely than Indians or Filipinos to say they can converse fluently in English. Roughly four-in-ten Chinese (43%) and Japanese (39%) immigrants say they can carry on a conversation in English very well, as do 30% of Koreans. Vietnamese immigrants are among the least likely to say they are fluent in English. Only 21% of foreign-born Vietnamese Americans say they can carry on a conversation in English very well.

Among all Asian immigrants, those who are less fluent in English are somewhat more likely to place a high value on maintaining their native language. Fully 57% of those who say they cannot carry on a conversation in English very well say it is very important that future generations of their ethnic or country of origin group who live in the U.S. be able to speak their native language. By contrast, among Asian immigrants who say they can converse very well in English, only 41% place a high value on future generations continuing to speak their native language.

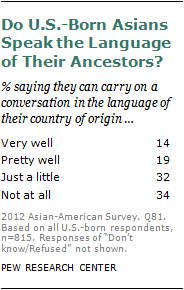

For native-born Asian Americans, the challenge is not mastering English, but rather maintaining some connection to the language spoken in their country of origin. Relatively few U.S.-born Asian Americans are fluent in their native or ancestral language. Asian Americans who were born in the U.S. were asked to assess their ability to converse in the language most closely identified with their country of origin. For example, Chinese Americans were asked how well they can carry on a conversation in Chinese, both understanding and speaking.54 Overall, only 14% of respondents said they can carry on a conversation in the language of their country of origin very well, and 19% said they can carry on a conversation in that language pretty well. Fully two-thirds said they can carry on a conversation in their native or ancestral language “just a little” (32%) or “not at all” (34%).

Younger, native-born Asian Americans are more likely than their older counterparts to say they can carry on a conversation in the language spoken in their family’s country of origin. Among those under age 55, 37% say they can converse very well or pretty well. Among those ages 55 and older, only 16% say the same.55

Asian Americans, Hispanics and Language

When compared with Hispanics, Asian Americans place much less emphasis on maintaining ties to their native or ancestral languages. While a strong majority say it is at least somewhat important to them that future generations be able to speak the languages of their Asian countries of origin, only 45% say this is very important. Among Hispanics, fully 75% say it is very important to them that future generations be able to speak Spanish.

Hispanics are more united in their views on this topic, just as they are more united in their linguistic history. Though Hispanics come to the U.S. from more than 20 different nations, all of those nations are Spanish-speaking. This common bond is something Asian-American immigrants do not share—coming from a host of countries with their own unique linguistic traditions.

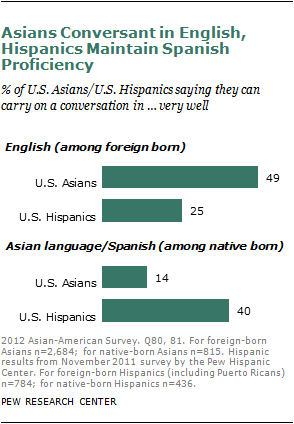

Among foreign-born immigrants, Asians are much more likely than Hispanics to speak fluent English. Roughly half of Asian immigrants (49%) say they can carry on a conversation in English very well. Only 25% of Hispanic immigrants say the same. Among Hispanic immigrants, a solid majority (62%) say they can carry on a conversation in English just a little or not at all (compared with 25% of Asian immigrants).

While relatively few U.S.-born Asians say they can speak the language of their ethnic heritage, U.S.-born Hispanics remain closely connected to their Spanish-language origins. Four-in-ten U.S.-born Hispanics say they can carry on a conversation in Spanish very well (compared with only 14% of U.S.-born Asians who can do so in the language of their country of origin).