Asian Americans have a distinctive set of values and behaviors when it comes to parenthood, marriage and career. Compared with the U.S. population as a whole, they are more likely to be married, and Asian-American women are less likely to be unmarried mothers. They place greater importance than the general public on career and material success, and these values are evident in their parenting norms. About six-in-ten say most American parents don’t place enough pressure on their children to do well in school; only 9% say the same about parents from their own Asian heritage group.

Marriage and family are of central importance to virtually all Americans, regardless of their ethnic or racial background. But in recent decades, sweeping social changes have transformed the institutions of marriage and parenthood. A smaller share of adults in the U.S. are married (51% now, down from 69% in 1970),75 more babies are being born outside of marriage (41% in 2009, up from 11% in 1970), and fewer children are being raised by two married parents (63% in 2010, down from 82% in 1970). In most of these realms, today’s Asian Americans—particularly the foreign born—represent something of a throwback; their behaviors resemble the patterns that prevailed before these changes in American society took hold.

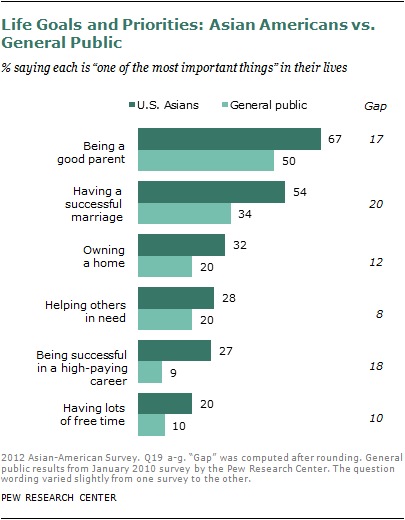

Asian Americans and the overall American public are in broad agreement that parenthood and marriage are at the top of the list of “the most important things” in life; other priorities such as career success, homeownership and helping others in need trail far behind. However, while the rank order is similar, Asian Americans place a higher level of importance on each priority compared with the general public.

Within the Asian-American population, there are a few key differences between immigrants and those born in the U.S. Foreign-born Asians place a higher priority on marriage, homeownership and career success than do their native-born counterparts. Indian Americans stand out from other Asian Americans for the emphasis they place on being a good parent. Vietnamese Americans stand apart from other groups in the value they place on homeownership and career success.

In addition to exploring Asian Americans’ values and priorities, this section will look at their views on appropriate parenting and the influence parents should have over their adult children. The image of the Asian American “tiger mom” may be overblown, but a majority of Asian Americans question whether most American parents put enough pressure on their children to do well in school. And a solid majority of Asian Americans say parents should have at least some influence over their adult children’s choice of spouse and career.

What Matters Most in Life?

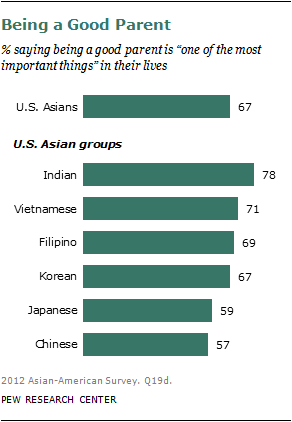

Survey respondents were asked how important each of six aspects of live is to them personally.76 Asian Americans place the highest priority on being a good parent. About two-thirds (67%) say this is “one of the most important things” in their lives, and an additional 27% say this is “very important but not one of the most important things.” Only 5% say being a good parent is “somewhat important” or “not important” to them personally.

A similarly worded question was asked of the general public in a 2010 Pew Research survey. The public also ranked being a good parent the top priority. However, a smaller share (50%) said this was one of the most important things in their lives. An additional 44% of American adults said being a good parent was very important to them but not the most important thing. There are similar gaps between U.S. Asians and the general public on all of these items. Part of this may be a result of slightly different question wording.77 However, the gaps may also be attributable to cultural differences between Asian Americans and the general public that influence the way in which respondents from each group answer this type of question.

When it comes to marriage and parenthood, the gap in attitudes between Asian Americans and the general public may also reflect different patterns of behavior in these realms. Overall, Asian-American children are more likely than all American children to be growing up in a household with two married parents. According to data from the 2010 American Community Survey, 80% of Asian-American children age 17 or younger were living with two married parents. This compares with 63% of all American children. In addition, only 15% of the Asian-American women who gave birth in the previous year were unmarried. This compares with roughly 40% of women giving birth among the general public.

Among U.S. Asians, Indian Americans are more likely than others to say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in their lives (78%). Chinese Americans (57%) and Japanese Americans (59%) are somewhat less likely than other Asian Americans to rank this as a top priority.

Whether an Asian American was born in the U.S. or outside of the U.S. does not have a significant impact on the priority placed on parenthood. Asian immigrants and U.S.-born Asians are equally likely to say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in their lives.

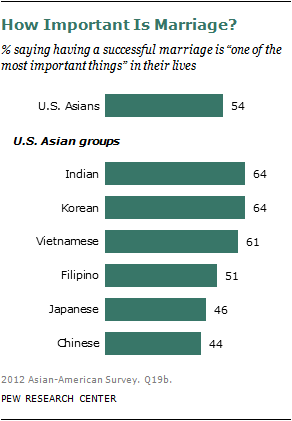

After parenthood, Asian Americans place the highest priority on having a successful marriage. Just over half (54%) say this is one of the most important things in their lives. An additional 32% say this is very important but not one of the most important things to them. Among U.S. Asian groups, those of Indian, Korean and Vietnamese heritage place a higher value on marriage than do the other three U.S. Asian groups.

Asian immigrants place a greater degree of importance on marriage than do Asians born in the U.S. Fully 57% of foreign-born Asians rank having a successful marriage as one of their top priorities, while 47% of native-born Asians give it the same ranking.

Compared with all American adults, Asian Americans place more importance on marriage. Among the general public, only about one-third (34%) say having a successful marriage is one of the most important things in their lives. On average, Asian-American adults are more likely than all U.S. adults to be married. In 2010, 59% of all Asian-American adults were married, compared with 51% among the general public. Among U.S. Asian groups, Indian-American adults are the most likely to be married (71%), while Japanese Americans are the least likely (53%).

Homeownership, Career Success, Altruism and Leisure

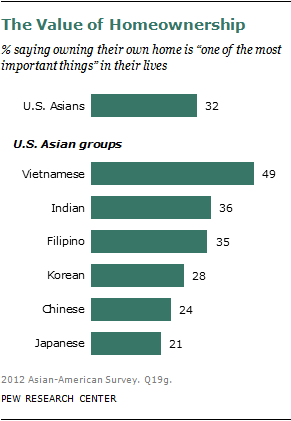

Parenthood and marriage are the top two priorities for both Asian Americans and the general public. After those is a second tier of items outside of the realm of family: homeownership, career success and helping others in need. Roughly one-third of Asian Americans (32%) say that owning their own home is one of the most important things in their lives. An additional 36% say this is very important to them but not one of the most important things. One-quarter (26%) say this is somewhat important, and 6% say it is not very important.

When compared with the general public, Asian Americans are more likely to place homeownership near the top of their list of life goals. Among U.S. adults, 20% say that owning a home is one of the most important things in their lives.

Vietnamese Americans are more likely than any other U.S. Asian group to place a high priority on owning a home. Roughly half (49%) say owning their own home is one of the most important things to them. By contrast, only 21% of Japanese Americans and 24% of Chinese Americans say the same.

As a group, Asian Americans are less likely than all U.S. adults to own their own home (58% vs. 65%). Among Asian immigrants, those who arrived in the last decade are much less likely to be homeowners than those who emigrated before 2000. In spite of this gap in homeownership, these two groups of immigrants are equally likely to say that owning a home is a top priority for them.

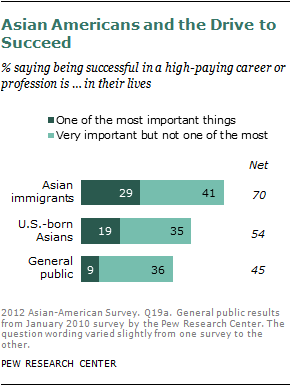

Many Asian Americans also value career success. Overall, 27% of U.S. Asians say being successful in a high-paying career is one of the most important things in their lives. Four-in-ten (39%) say this is very important but not one of the most important things. Some 27% say career success is somewhat important to them, and 6% say it is not important. The general public places significantly less importance on career success. Among all U.S. adults, only 9% say being successful in a high-paying career or profession is one of the most important things in their lives.

The drive for success is particularly strong among foreign-born Asian Americans. Roughly three-in-ten (29%) rank being successful in a high-paying career as a top priority, and 41% say this is very important to them though not one of the most important things in their lives. By comparison, 19% of U.S.-born Asians say career success is one of the most important things in their lives, and an additional 35% say it is very important.

Across U.S. Asian groups, Vietnamese Americans (42%) place the highest priority on career success. Japanese Americans are more in line with the general public on this measure: 12% rate being successful in a high-paying career as a top priority (as do 9% of all U.S. adults).

When it comes to helping others in need, 28% of Asian Americans say this is one of the most important things in their lives. An additional 44% say this is very important to them but not the most important thing, and 26% say this is somewhat important. Only 2% say this is not important to them. Compared with the general public, Asian Americans are somewhat more likely to place a high priority on helping others in need (20% of all American adults say this is one of the most important things in their lives).

Views on this are fairly consistent across U.S. Asian groups, with one exception. Chinese Americans are somewhat less likely than other Asian Americans to say helping other people in need is one of the most important things in their lives (17%).

Finally, respondents were asked how much importance they place on having lots of free time to relax or do things they want to do. Relative to the other five life goals included on the list, free time ranks at the bottom for Asian Americans (and near the bottom for the general public). One-in-five Asian Americans (20%) say this is one of the most important things in their lives, an additional 37% say this is very important but not one of the most important things, and 36% say it is somewhat important. Only 6% say having enough free time is not important to them.

Among all American adults, 10% say having lots of free time is one of the most important things in their lives and 43% say it is very important to them but not the most important.

There is some variance on this measure across U.S. Asian groups. Korean Americans (30%) and Vietnamese Americans (29%) are more likely than other Asian Americans to place a high value on having free time. By contrast, only 15% of Chinese Americans say having free time is one of the most important things to them. Filipino (19%), Indian (19%) and Japanese Americans (18%) are closer to the Chinese in this regard.

How Trusting Are Asian Americans?

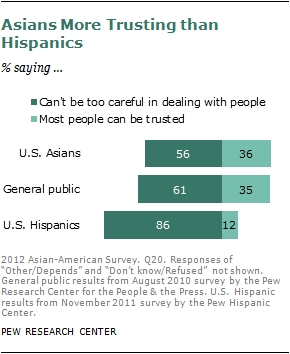

When it comes to trusting other people, the views of Asian Americans are similar to those of the general public. Respondents were asked to answer a classic social science question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” Overall, 36% of Asian Americans say most people can be trusted, while a 56% majority says you can’t be too careful. In a 2010 Pew Research survey of the general public, 35% of American adults said most people can be trusted and 61% said you can’t be too careful in dealing with people (slightly higher than the share of Asian Americans who say that).

The views of Asian Americans regarding social trust are in sharp contrast to those of Hispanics. Among Hispanics, only 12% say they believe most people can be trusted. An overwhelming 86% majority says you can’t be too careful in dealing with people. Within the Asian-American population, immigrants and those born in the U.S. express similar levels of trust. Within the Hispanic population, immigrants are less trusting than the native born. Fully 89% of Hispanic immigrants say you can’t be too careful in dealing with people; 81% of U.S.-born Hispanics say the same.

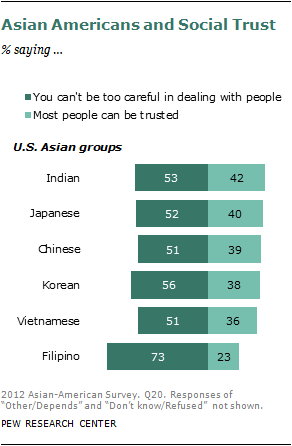

The level of social trust Asian Americans express is remarkably consistent across U.S. Asian groups, with one exception. Filipino Americans are less trusting than any other group. Only 23% say most people can be trusted, and 73% say you can’t be too careful in dealing with people.

Parenting, Pressure and Children: How Much Is Too Much?

Amy Chua set off a swirl of controversy last year with her Wall Street Journal essay entitled, “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior.” The article was excerpted from Chua’s book, “Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother,” in which she details her strict approach to parenting and her unwillingness to accept anything short of academic excellence from her children. Chua contrasted her approach to parenting with the more nurturing, accepting approach taken by most Western parents.

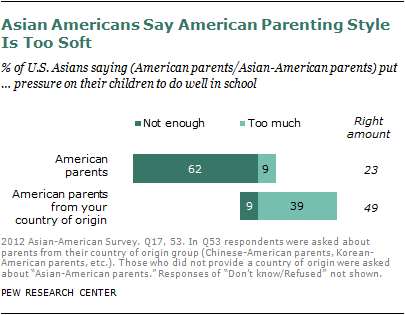

The opinions of Asian Americans suggest that they, too, see a major gap between their own approach to parenting and the approach taken by most American parents. Survey respondents were first asked whether, on the whole, they think American parents put too much pressure on their children to do well in school, not enough pressure, or about the right amount of pressure. A strong majority of Asian Americans (62%) say American parents do not put enough pressure on their children. An additional 23% say American parents put about the right amount of pressure on their children. Only 9% say they put too much pressure on their children to do well in school.

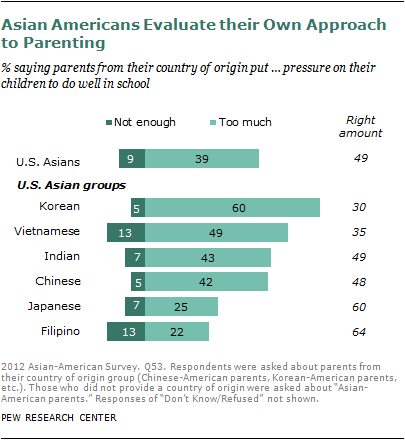

Later in the survey, respondents were asked about the approach taken by parents from their country of origin or ancestral background. Chinese respondents were asked about Chinese American parents, Koreans were asked about Korean American parents, and so on. While roughly half of all Asian Americans (49%) say that parents from their Asian group put about the right amount of pressure on their children to do well in school, a large minority (39%) says Asian-American parents put too much pressure on their children. Only 9% say they put too little pressure on their children.

Views on the parenting styles of Americans and Asian Americans do not differ significantly by gender or parental status. Attitudes do differ, however, by educational attainment. When thinking of the amount of pressure most American parents put on their children to do well in school, Asian Americans with a college degree are much more likely than those with no college education to say most American parents don’t put enough pressure on their children (66% of Asian-American college graduates say this, compared with 50% of those with a high school diploma or less).

In addition, Asian-American college graduates are more likely than those who have not attended college to endorse the approach taken by parents from their own country of origin. While roughly half (51%) of Asian-American college graduates say parents from their country of origin put about the right amount of pressure on their children to do well in school, only 43% of Asian Americans with no college experience share this view.

U.S.-born Asian Americans are more critical of most American parents than are their foreign-born counterparts. Among Asian Americans who were born in the U.S., 71% say most American parents do not put enough pressure on their children to do well in school. This compares with 59% of foreign-born Asian Americans. And when it comes to their own parenting, U.S.-born Asian Americans have a somewhat more positive view of the approach taken by parents from their own Asian group than do those born outside the U.S. Some 56% of U.S.-born Asian Americans say parents from their ancestral background put the right amount of pressure on their children. Among foreign-born Asian Americans, that share is 46%.

Across U.S. Asian groups, opinion is fairly consistent with regard to the way Americans raise their children. About half or more of each group say most American parents do not put enough pressure on their children to do well in school, while very few say American parents put too much pressure on their children. Indian Americans are more likely than other Asians to say American parents are too easy on their children (71%).

There is much less agreement about the pressure that Asian-American parents place on their children. Filipino Americans and Japanese Americans are more likely than other groups to say that parents from their own country of origin put about the right amount of pressure on their children to do well in school. In fact, majorities from each group (64% of Filipinos and 60% of Japanese) say parents from their group take the right approach with their children.

The balance of opinion is quite different among most other U.S. Asian groups. A solid majority of Korean Americans (60%) say Korean-American parents put too much academic pressure on their children; only 30% say they put the right amount of pressure on their children. Among Vietnamese Americans, 49% say Vietnamese-American parents put too much pressure on their children, while 35% say the amount of pressure is about right.

Indian Americans and Chinese Americans are more evenly divided. Roughly four-in-ten from each group say parents from their country of origin put too much pressure on their children. At the same time, roughly half from each group say these parents put about the right amount of pressure on their children.

The Scope of Parental Influence

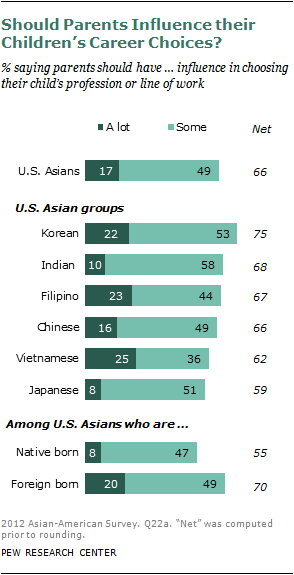

For many Asian Americans, parental influence extends beyond pushing their young children to do well in school. Two-thirds of Asian Americans say parents should have at least some influence over a child’s career choice and nearly as many (61%) say parents should have some influence over their child’s choice of spouse.

Survey respondents were asked how much influence, if any, parents should have in choosing a child’s profession or line of work. Overall, 17% of Asian Americans say the parents should have “a lot of influence” in this regard, and an additional 49% say parents should have “some influence.” Roughly one-in-four say parents should not have too much influence in choosing a child’s profession, and 9% say parents should have no influence at all.

Asian Americans with adult children, for whom this may be less of a hypothetical question, are more likely than those who do not have children to say parents should have some influence over career choices. About two-thirds (68%) of parents with children ages 18 and older say parents should have at least some influence over what profession a child chooses. This compares with 58% of those with no children.

Asian Americans who have graduated from college are somewhat more likely than those without a college degree to say parents should have some influence over the career choices their child makes—70% of colleges graduates and 62% of non-college graduates say parents should have a lot of influence or some influence over their child’s career choices.

Perhaps the biggest gap in opinion on this measure of parental influence is between foreign-born and native-born Asian Americans. Those who were born outside of the U.S. are much more likely than those born in the U.S. to say parents should have some influence on their child’s choice of profession or line of work. Seven-in-ten Asian immigrants say parents should have a lot of (20%) or some (49%) influence. By contrast, 55% of U.S.-born Asian Americans say parents should have at least some influence in this regard (8% a lot, 47% some). This pattern is consistent within the Chinese-American community with a higher share of the foreign born saying parents should have some influence over their child’s career choice. However, among Japanese Americans and Filipino Americans, there is no significant difference between the native born and foreign born on the question of parental influence over career decisions.78

Across U.S. Asian groups, Korean Americans are more likely than other Asians to say parents should have at least some influence over their child’s career choices. Three-quarters say parents should have a lot (22%) or some (53%) influence. Japanese Americans are less likely than other U.S. Asians to say parents should have influence over their children’s career choices (8% say a lot, 51% say some).

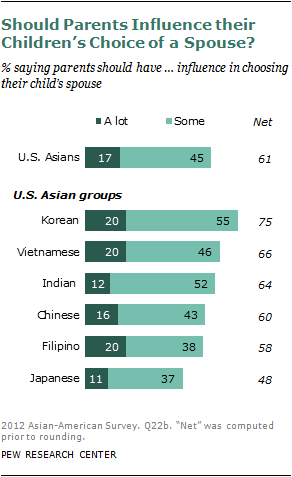

Respondents were also asked how much influence parents should have in choosing a child’s spouse. Overall, 61% of Asian Americans say parents should have at least some influence—17% say a lot of influence, and 45% say some influence. Women are somewhat more likely than men to say parents should have some influence over their child’s choice of a spouse (65% of women vs. 58% of men).

Asian Americans who have grown children are more likely than those without children to say a person should be influenced by his or her parents when it comes to choosing a spouse (66% vs. 54% say parents should have at least some influence). About one-in-five parents with children ages 18 and older say they should have a lot of influence. This compares with only 12% of those with no children.

Once again there is a substantial gap in opinion between foreign-born and native-born Asians regarding the scope of parental influence. Asian immigrants are much more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to say that parents should have at least some influence over a child’s choice of a spouse (65% of foreign born vs. 49% of native born).

There are significant differences across U.S. Asian groups as well. Korean Americans are more likely than other Asians to say parents should have some influence over their child’s choice of a spouse (75% say a lot of or some influence). Japanese Americans are the least likely to say parents should have influence in this area; about half (48%) say parents should have a lot of influence or some influence.