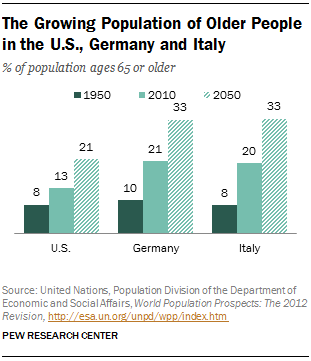

The graying of the population is one of the most significant demographic shifts occurring in the U.S. today. Some 13% of Americans are now ages 65 and older, and that share is projected to rise to 21% by the middle of this century. Population aging has been even more rapid in other developed countries, such as Germany and Italy. Already one-in-five people in each country is 65 or older. These two countries provide a glimpse of what the U.S. population may look like by mid-century.

Italy and Germany not only have higher shares of older residents than any other countries in Europe or North America, but they also have the highest old-age dependency ratios, meaning they have a greater number of older adults for every 100 working-age adults (ages 15-64). In the U.S., the old-age dependency ratio stands at 19.5, meaning that there are about 20 people ages 65 and older for every 100 people ages 15-64. In both Germany and Italy, this ratio has already reached 30.2

While broad comparisons among the U.S., Germany and Italy are instructive, circumstances in the three countries diverge in significant ways. In particular, the financial profile of those ages 65 and older and their sources of income vary dramatically across the three nations. In the U.S., a relatively small share of older Americans’ income comes from government transfers, while in Italy, virtually all old-age income is derived from the government, and Germany falls in the middle on this measure. In addition, one-in-five people ages 65 and older in the U.S. are living in poverty, double the share of those in Germany and Italy.

This chapter explores the changing age structures in the U.S., Germany and Italy since 1950, as well as the projected trajectory of each country in the coming decades. In addition, it compares and contrasts the current economic situation of the young and the old in each country, as well as the sources of income for older adults across the three countries.

The Demographic Context

In the era immediately following World War II, the U.S. did not look so different from its European neighbors in terms of its age structure. However, since that time, the U.S. has been aging at a slower rate than Germany and Italy, due in part to its relatively high fertility and high rate of immigration. Both of these factors have buoyed the share of the U.S. population younger than age 65, and they will continue to do so, according to United Nations estimates.

In 1950, the median age in the U.S. was 30, meaning an equal share of the population was older than 30, as was younger than 30. By 2010, the median age had risen markedly to 37, and it is projected to continue rising, reaching about 41 by 2050.

The median age has risen at an even quicker pace in Italy and Germany. In 1950, the median age in Germany was 35 – five years higher than in the U.S. By 2010, the median age was seven years higher than in the U.S., and by 2050, the median age in Germany is projected to be 51 years – fully 11 years higher than in the U.S. Meanwhile, the median age in Italy in 1950 was 29, a bit lower than that of the U.S. By 2010, it stood at 43, and it may reach 50 by 2050.

Higher median ages are driven, in part, by the increasing share of the population that is ages 65 years or older. In the U.S., that share stood at 13% in 2010, up from just 8% in 1950. By 2050, it is expected that about one-in-five people in the U.S. (21%) will be at least 65 years old. In Germany and Italy, this is already the case – 20% of Italians and 21% of Germans were at least 65 in 2010. And by 2050, one-third of the population in each of these countries will have reached this milestone.

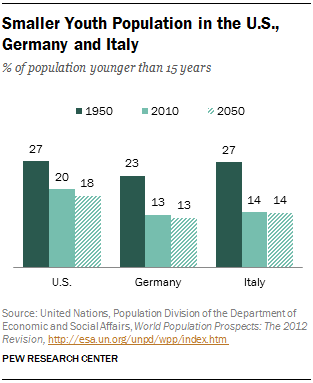

On the flip side, the share of young people in the U.S. is declining. In 1950, fully 27% of Americans were less than 15 years of age; in 2010, that share was 20%. It is expected to fall a bit more in the coming years, to about 18% by 2050. The share of young people in Italy has fallen more rapidly. As in the U.S, about a quarter of Italians (27%) were less than 15 years of age in 1950. By 2010 that share had fallen to 14%, where it is expected to remain for the coming decades. In Germany the profile is similar – 13% of Germans are younger than 15 today, and that pattern is expected to hold into 2050.

Continued increases in life expectancy, in the U.S. and elsewhere, have contributed to the rapid rise in aging populations. In 1950, the average U.S. life expectancy at birth was about 69 years. It now stands at 79 and is expected to increase even more, to about 84 by 2050. Germany and Italy have experienced even more rapid increases in life expectancy. While both countries had life expectancies below that of the U.S. in 1950, they now have surpassed the U.S. on this measure. Italians born in 2010 were expected to live until age 82 on average, and by 2050, their life expectancy may reach 88 years, according to UN projections. The same sources predict that a baby born in Germany in 2010 could expect to live until the ripe old age of 81, and by 2050 to 86 years.3

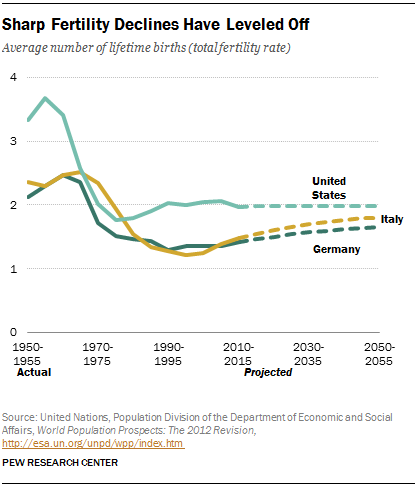

In the U.S. the relatively robust fertility rate has slowed the aging of the population, while in Germany and Italy, lower fertility has hastened it. In 2010, the total fertility rate in the U.S. stood at about 2. In other words, American women were expected to have about two children in their lifetimes, on average.4 At the same time, the total fertility rate in Germany and Italy has plummeted to about 1.4 and 1.5 children per woman, respectively. Projections suggest that in the coming decades, the total fertility rate in the United States will likely remain at about two children per woman. Come 2050, the U.S. rate will still be higher than that of Germany or Italy, where total fertility rates are projected to reach 1.7 and 1.8, respectively.

Financial Well-Being of the Young and Old

Since the enhancement of government-funded social programs such as Medicare in the mid-1960s, the welfare of older people in the U.S. has improved dramatically, while it has declined among young adults. For example, the share of older households in poverty dropped more than 20 percentage points between 1967 and 2010, while the share of households in poverty that are headed by someone age 35 or younger increased by more than 9 percentage points.5

Yet, even with improvements in financial well-being, the poverty rate among older U.S. adults remains much higher than among people ages 65 and older in Germany or Italy. About one-in-five older Americans are poor.6 This rate is almost twice as high as in Germany and Italy, where 11% of the older population is in poverty.

Income levels among older Americans vary widely, with some in this age group enjoying considerable wealth, even as others struggle economically. Thus, despite higher poverty rates, on average, people ages 65 or older in the U.S. are doing at least as well as their European counterparts, in terms of their incomes relative to the national mean income. All told, the incomes of U.S. adults ages 65 and older are equivalent to about 92% of the national average income, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). This is similar to the situation of older people in Italy, whose income is 93% of the national average, and higher than the relative income of older people in Germany, which is about 85% of the national average.

Older adults in the U.S. are in a much stronger position than their younger counterparts in terms of wealth accumulation, and this gap is growing. While the median net worth of households headed by people younger than 35 declined by 44% from 1984 to 2011, it rose by 37% in households headed by persons ages 65 or older. Put another way, in 1984, older households had 11 times the wealth of households headed by people ages 35 or younger; in 2011 the wealth of older households was 26 times that of younger households.

This age gap in financial well-being accelerated in recent years, likely spurred by the fact that young adults were particularly hard hit by the Great Recession. In the U.S., 18- to 24-year-olds experienced the biggest increases in unemployment of any age group, by far. And even among those Americans who were able to find work during the recession, young adults experienced the largest declines in weekly earnings, losing 6% on average.

Meanwhile, young adults in Italy and Germany also suffered as a result of the economic downturn, and many are still struggling—especially in Italy. In 2013, among those ages 20 to 24, annual average unemployment in Italy was a staggering 37% (compared with 13% in the U.S. and 8% in Germany), according to the OECD.

Sources of Income for Older Adults

Demographic changes in Italy, Germany and the U.S. are placing a growing strain on these countries’ social security systems. All three systems are financed through worker contributions. In Europe, more than in the U.S., the growing number of older adults along with a shrinking pool of younger active contributors has made it difficult to fund pensions for current retirees.

Broadly speaking, the government-funded pension system in the United States is similar to that offered in Germany and Italy – for most people, it is based on lifetime earnings.7 However, the role that public transfers play in old-age income varies markedly by country.

Older adults living in the U.S. receive a smaller share of their income from the government than do older adults living in Italy and Germany. The OECD estimates that 38% of income among those ages 65 and older in the U.S. comes from public sources such as Social Security, while in Germany and Italy, about 70% of income comes from government transfers.8

In the U.S. today, a significant share of income among older adults (32%) comes from current earnings. In Italy, earnings comprise 20% of income for older people, and in Germany, they comprise only 13% of income among those ages 65 or older. These dramatic national differences in the importance of earnings among older people are driven, in part, by very different patterns of labor force participation. Among people ages 65 to 69, 30% are still employed in the U.S., compared with just 13% of those in Germany, and 8% of those in Italy.

An additional 30% of the income among older people in the U.S. comes primarily from private pensions, such as 401(k)s. In Germany, these sources comprise just 13% of older citizens’ income, and in Italy, just 7%.9