Most police officers are satisfied with their department as a place to work and are strongly committed to ensuring their agency is successful. But police offer less positive views about some key aspects of their department’s processes and policies. For example, officers are divided on whether the disciplinary process in their department is fair. And a majority of officers do not feel that officers who are consistently doing a poor job are held accountable.

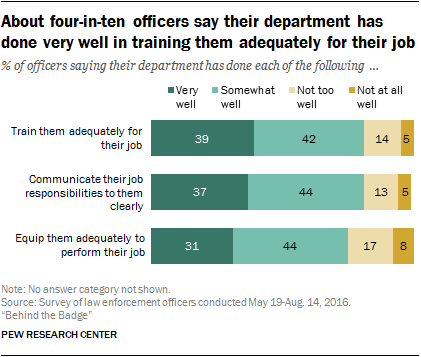

Police also indicate that their department does not have sufficient resources or training. A vast majority of officers say their department does not have enough officers to adequately police the community. And only about three-in-ten (31%) officers say their department has done very well in equipping them adequately to do their job. Roughly four-in-ten officers say their department has done very well in training them adequately to perform their job (39%) and communicating their job responsibilities clearly (37%).

The survey also asked officers about their views on the use-of-force guidelines in their department. About a quarter of officers (26%) say that their department’s use-of-force guidelines are too restrictive – 73% say the guidelines are about right. But only about a third of officers (34%) say that their department’s use-of-force guidelines are very useful when they are confronted with situations where force may be necessary.

When it comes to preventing the use of unnecessary force, an overwhelming majority say officers should be required to intervene when they think another officer is about to use unnecessary force.

This chapter examines how police officers across the nation view the leadership and the internal processes and policies within their own departments. It also explores officers’ concerns about how their colleagues interact with the public.

Most officers are satisfied with their department and committed to its success

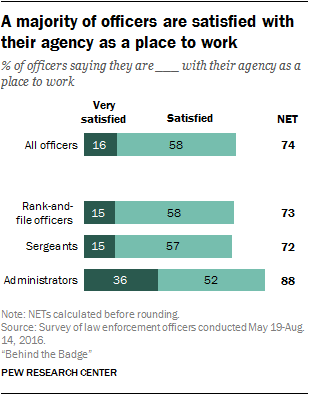

Roughly three-quarters (74%) of police officers say they are satisfied with their agency as a place to work, although relatively few (16%) say they are very satisfied. Levels of satisfaction with their department vary by officer’s rank. While majorities of each rank say they are at least satisfied with their agency as a place to work, administrators are about twice as likely to say that they are very satisfied with their agency (36% vs. 15% of rank-and-file officers and sergeants).

Newer officers (25%) are also more likely to express a high level of satisfaction with their department than those who have been in the field for five or more years (15%).

Overall, officers express a firm commitment to their department: Almost all officers strongly agree (60%) or agree (36%) that they are strongly committed to making their agency successful. This is consistent across all demographic groups and agency characteristics.

Support for top leadership’s direction is stronger in smaller agencies

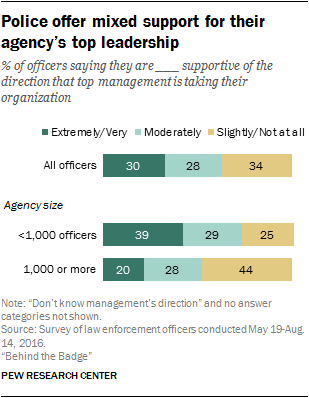

Police offer mixed support for their top leadership. Three-in-ten officers say they are extremely or very supportive of the direction their top management is taking the organization, and 28% say they are moderately supportive. Roughly a third (34%) of officers say they are slightly supportive or not supportive at all.

Police in agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers are more supportive of their leadership’s direction than those in larger agencies. About four-in-ten (39%) officers at agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers say they are extremely or very supportive of their management’s direction. Only 20% of officers in departments with at least 1,000 say the same; 44% of officers in these departments say they are slightly or not at all supportive of their top management’s direction.

Most officers feel their supervisor treats them and their colleagues with respect

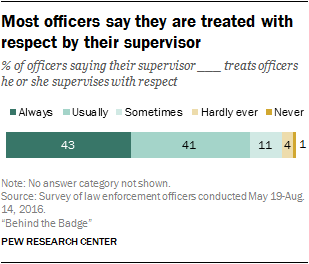

About four-in-ten (43%) officers say their supervisor always respects them and their colleagues, while about as many (41%) say this is usually the case; 15% say their supervisor sometimes, hardly ever or never treats the officers he or she supervises with respect.

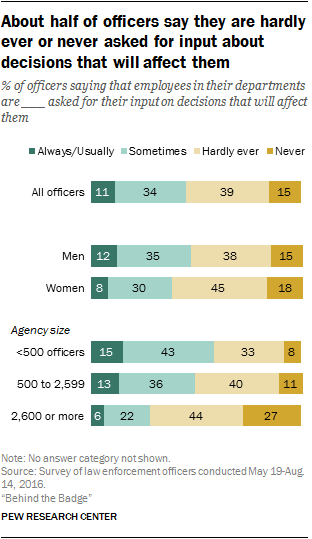

When asked how often employees in their department are asked for input on decisions that will affect them, roughly half (54%) of officers say this is hardly ever (39%) or never (15%) the case. Still, 45% of officers say they are at least sometimes asked for input about decisions that will affect them.

Women are more likely than men to say employees are hardly ever or never asked for their input. Among female officers, 63% say that they and their co-workers are hardly ever (45%) or never (18%) asked for their input. By comparison, 53% of men say the same (comprising 38% who say hardly ever and 15% who say never).

Police in large departments (with 2,600 officers or more) are about three times as likely as those in small departments to say they are never asked for their input. Just 8% of police in departments of fewer than 500 officers say they are never asked for input on decisions that will affect them. By comparison, 27% of police in departments with at least 2,600 officers say the same.

For promotions and assignments, minorities and women are more likely to say their counterparts are treated better

In America’s police departments, women and Hispanics are underrepresented despite their growing shares in recent decades. In 2013 (the most recent data available), blacks made up the same share of local police officers as they did in the U.S. adult population. (See “Growing diversity inside America’s police departments” textbox for more details on diversity in U.S. police departments.) The survey asked how women and minority officers are treated relative to their counterparts when it comes to assignments and promotions in their department.

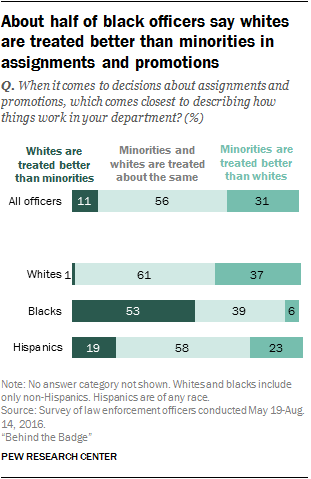

Some 56% of officers say that minorities and whites are treated about the same way when it comes to assignments and promotions, while about three-in-ten (31%) say minorities are treated better than whites in these cases. Roughly one-in-ten (11%) officers say that whites are treated better than minorities when it comes to assignments and promotions in their department.

But officers of different racial and ethnic backgrounds offer vastly different views on how minorities are treated in comparison to whites when it comes to assignments and promotions. Roughly six-in-ten white (61%) and Hispanic (58%) officers say that minorities and whites are treated about the same. By contrast, about half (53%) of black officers say that whites are treated better than minorities, while about one-in-five (19%) Hispanic officers and only 1% of white officers say the same.

About four-in-ten (37%) white officers say that minorities are treated better than white officers when it comes to decisions about assignments and promotions. By comparison, 23% of Hispanic officers and 6% of black officers say minorities are treated better than whites.

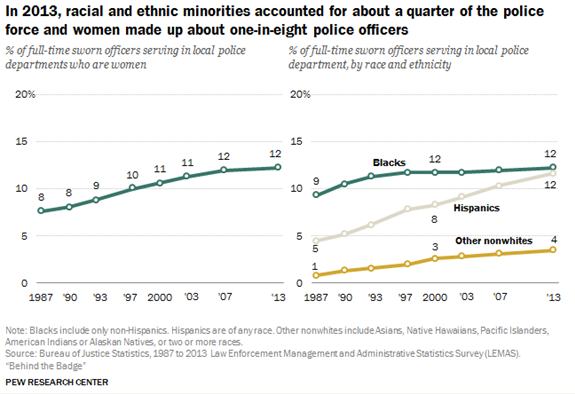

Growing diversity inside America’s police departments

America’s police departments have become increasingly diverse since the late 1980s. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, about 504,000 sworn police officers were employed in local U.S. police departments in 2013, the most recent year for which data were available.7 Among full-time officers, 12% were women in 2013, up from 8% in 1987. Women accounted for about one-in-ten supervisory or managerial positions and 3% of local police chiefs in 2013 (these data were collected for the first time in 2013). In general, departments that serve larger populations tend to have a higher share of women on their police force and a higher share of female supervisors.

Police departments have also become more racially and ethnically diverse: In 2013 more than a quarter (27%) of officers were racial or ethnic minorities, up from 23% in 2000. Some 12% of full-time local police officers in 2013 were black, equal to their share of all U.S. adults. Another 12% of full-time officers were Hispanic, compared with 15% of U.S. adults in 2013. While the share of police officers who are black has remained largely the same since 2000, the share who are Hispanics has grown by about 3 percentage points.8

Roughly four-in-ten female officers say men are treated better when it comes to assignments and promotions

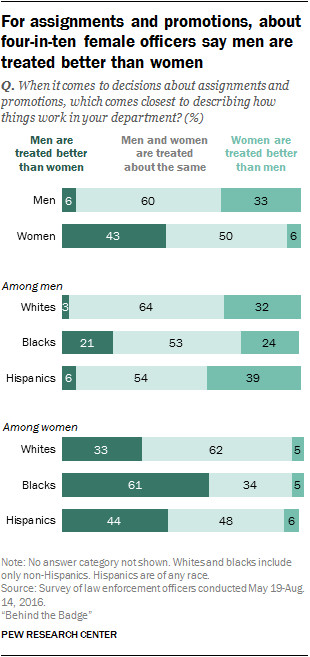

More than half (59%) of officers say that when it comes to assignments and promotions, men and women are treated the same in their department, while about three-in-ten (28%) say women are treated better than men. Some 12% say that men are treated better than women in these cases.

Views on how men and women are treated in their department vary greatly by gender. About four-in-ten (43%) women say that men are treated better than women when it comes to assignments and promotions, but only 6% of men say the same. And a third of men say that women are treated better in these cases, compared with just 6% of women. Six-in-ten men and half of women say they are treated about the same when it comes to assignments and promotions.

Black men and women are more likely than their white counterparts to say that men are treated better than women in their departments. Among men, 21% of black officers and 3% of white officers say this. Just 6% of Hispanic men say that men are treated better than women.

Among women, black officers are about twice as likely as white officers to say that men are treated better than women when it comes to assignments and promotions (61% vs. 33%). Some 44% of Hispanic women say this is the case.

It’s worth noting, however, that across racial and ethnic groups, female officers are far more likely than their male counterparts to say men in their departments are treated better than women when it comes to assignments and promotions. Men across all major racial and ethnic groups are more likely than their female counterparts to say that women are treated better than men.

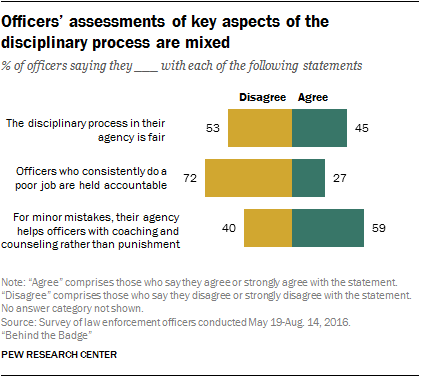

Officers are divided on the fairness of their agency’s disciplinary process

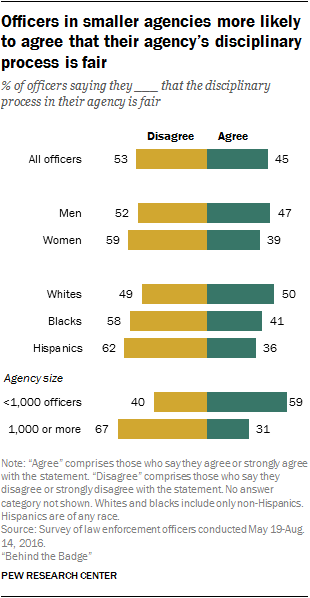

Police offer mixed assessments on some key aspects of the disciplinary process in their departments. When asked if they agree or disagree with the statement that the disciplinary process in their agency is fair, officers are divided: 45% say they strongly agree or agree with this statement; 53% say they disagree or strongly disagree.

But a majority (72%) of officers say they disagree (47%) or strongly disagree (25%) that officers in their department who consistently do a poor job are held accountable. Roughly a quarter (27%) of officers agree, including just 3% who strongly agree. While similarly large shares of officers across all demographic groups disagree that officers who consistently do a poor job are held accountable, police in larger agencies with at least 1,000 officers are particularly likely to disagree (81% vs. 63% of police in departments with fewer than 1,000 officers).

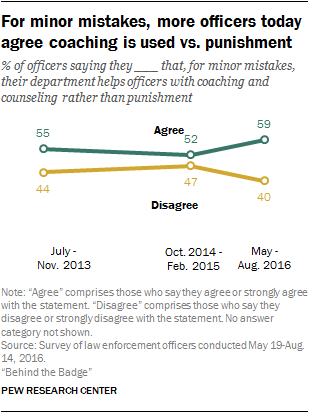

Police offer a slightly more positive view when asked whether they agree or disagree that their department helps officers with coaching and counseling rather than punishment for minor mistakes: About six-in-ten (59%) agree, while 40% disagree. Officers in departments of fewer than 1,000 officers are more likely than those in larger departments to agree that their department helps officers with coaching and counseling rather than punishment for minor mistakes (69% vs. 49%). Officers of higher rank are also more likely to say this is the case (79% of administrators agree vs. 57% of rank-and-file officers).

The share of officers who agree that for minor mistakes the department helps officers with coaching and counseling rather than punishing them is up 7 percentage points since it was last asked about two years earlier (October 2014 to February 2015). At that time, officers were divided on the topic: 52% said they agreed with the statement that in their department officers are helped with coaching and counseling rather than punished for minor mistakes, while 47% disagreed.

Men and white officers more likely than counterparts to agree that their agency’s disciplinary process is fair

Views of the disciplinary process being fair vary by the characteristics of the officers and the department. Men are more likely than women to say they agree that the disciplinary process in their agency is fair (47% vs. 39%).

While half of whites agree that the disciplinary process in their agency is fair, 41% of black officers and 36% of Hispanic officers say the same.

Police in smaller agencies are about twice as likely as those in larger agencies to agree that the disciplinary process in their department is fair. About six-in-ten (59%) of those in agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers agree with the statement, while about three-in-ten (31%) in agencies with 1,000 or more officers agree.

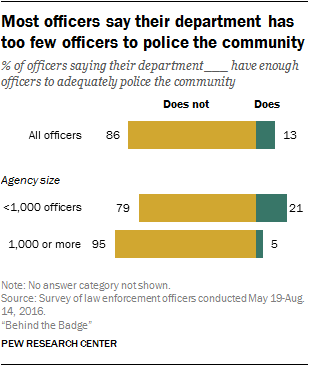

A majority of officers say there are not enough police in the community where they work

Fully 86% of officers say their department does not have enough officers to adequately police the community. Similarly large shares of officers say this across all demographic groups and agency characteristics. But police in agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers are about four times as likely as those in larger agencies to say they do have enough officers to police the community (21% vs. 5%).

Officers of higher rank are also more likely to say that their department has enough officers. About a quarter (23%) of administrators say their department has enough officers to adequately police the community, compared with 13% of rank-and-file officers and 10% of sergeants.

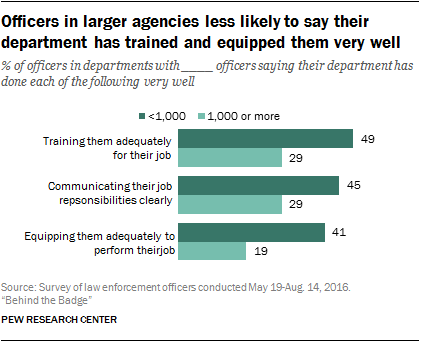

The survey also asked officers how well their department has trained and equipped them. Roughly four-in-ten officers say that their department has done very well in training them adequately to do their job (39%) and in communicating their job responsibilities to them clearly (37%). And about three-in-ten (31%) say the department has done very well in equipping officers to adequately perform their job. In all, a majority of officers say that their department has done at least somewhat well in each of these areas.

Police in larger agencies are considerably less likely to say their department has done very well in each of these aspects. For example, 29% of police in agencies with at least 1,000 officers say their department has done very well in training them adequately for their job, compared with 49% of police in agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers. Likewise, just 19% of police in agencies with 1,000 or more officers say their department has done very well in equipping them adequately to perform their job, compared with 41% of those in smaller agencies.

Officers with less than five years of experience are more likely than those with more experience to say their department has done very well in each of these areas. For example, 57% of officers with less than five years of experience say their department has done very well in training them adequately for their job, compared with 37% of officers with five or more years of experience.

About a third of officers say their department’s use-of-force guidelines are very useful

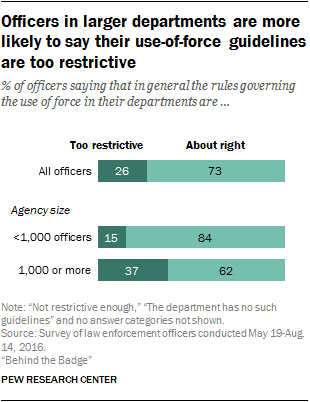

When asked whether their department’s use-of-force guidelines are too restrictive, not restrictive enough or about right, a majority (73%) of officers say that their department’s rules are about right. Still, about a quarter (26%) say the use-of-force guidelines are too restrictive. Only about 1% say their department’s guidelines are not restrictive enough.

While similar shares of officers across demographic groups say their use-of-force rules are about right, police in larger agencies with at least 1,000 officers are about twice as likely as officers in smaller agencies to say that their department’s rules governing the use of force are too restrictive (37% vs. 15%).

Rank-and-file officers and sergeants are somewhat more likely than administrators to say their department’s rules governing the use of force are too restrictive. Roughly a quarter of rank-and-file officers (27%) and sergeants (24%) say this is the case, compared with 17% of administrators.

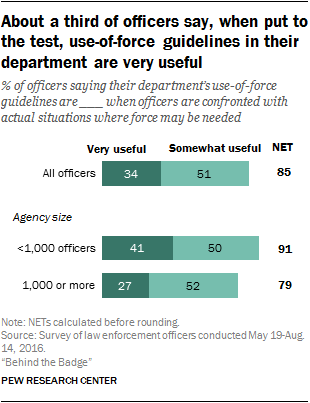

Roughly a third (34%) of officers say that their department’s use-of-force guidelines are very useful when they are confronted with actual situations where force may be needed. An additional 51% say they are somewhat useful. Some 14% say they are not too useful or not at all useful.

Those in agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers are considerably more likely than those in larger agencies to say their agency’s guidelines are very useful. About four-in-ten (41%) in agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers say this, compared with 27% in agencies with at least 1,000 officers.

Administrators are also substantially more likely than rank-and-file officers to say their department’s guidelines are very useful (49% vs. 33%, respectively).

Police worry more that their fellow officers will spend too much time versus not enough time diagnosing a situation before acting

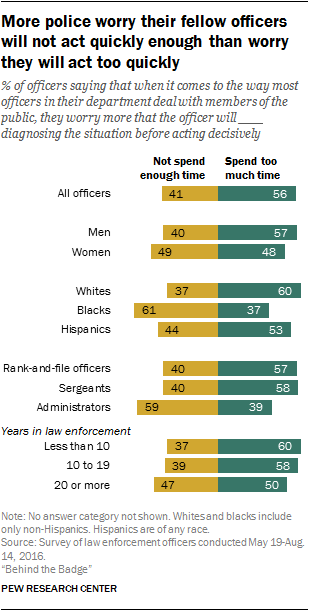

More police officers worry about their fellow officers spending too much time diagnosing a situation before acting (56%) than about their fellow officers not spending enough time before acting decisively (41%).

Black officers and administrators stand out as the only groups studied that are more likely to say they worry more that officers in their department will not spend enough time diagnosing the situation before acting than that they will spend too much time.

About six-in-ten (61%) black officers say they worry more that officers will not spend enough time diagnosing the situation before acting, compared with 37% of white officers and 44% of Hispanic officers. And 59% of administrators say the same. By comparison, just 40% of rank-and-file officers and sergeants say they worry more that officers will not spend enough time diagnosing the situation before acting.

Men are more likely than women to say that officers in their department will spend too much time diagnosing the situation before acting (57% vs. 48%, respectively). And about six-in-ten officers with less than 20 years of experience say they worry more that officers will spend too much time diagnosing a situation before acting, compared with half of officers with 20 or more years of experience.

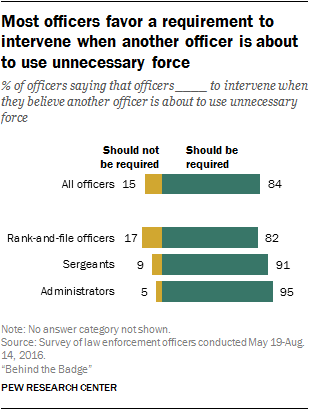

Most officers say that they should be required to intervene when another officer is about to use unnecessary force

One policy recommendation to protect community members and police from unnecessary force is to require police to intervene when they think another officer may use unnecessary or excessive force.9

A majority (84%) of police say that officers should be required to intervene when they believe another officer is about to use unnecessary force, while just 15% say they should not be required to intervene.

Majorities of police officers across all characteristics say that officers should be required to intervene in these scenarios. But rank-and-file officers are more likely than those of higher ranks to say they should not be required to intervene when they think another officer is about to use unnecessary force (17% of rank-and-file officers say this, compared with 9% of sergeants and 5% of administrators).

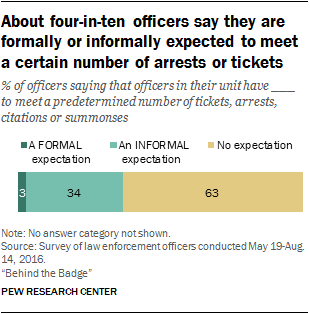

About four-in-ten officers say they are expected to meet a quota for arrests or tickets

In recent years quotas – which have been used to measure performance for officers – have been criticized for a range of reasons related to their limits in assessing the quality of policing. And today, in several states ticket and arrest quotas are illegal.

While few officers (3%) say that they are formally expected to meet a predetermined number of tickets, arrests, citations or summonses in their unit, about a third (34%) of officers say there are informal expectations for meeting a predetermined number of arrests or tickets. A majority (63%) say officers in their unit are not expected to meet any predetermined number of tickets or arrests.

Rank-and-file officers – those who routinely monitor an area, issue tickets and make arrests – are particularly likely to say there are informal expectations. Some 36% of rank-and-file officers say there is an informal expectation for meeting a predetermined number of tickets or arrests; 29% of sergeants and 23% of administrators say the same.