In police departments around the country, officers are often sent out to start their shift with an admonition from their supervisor – something to the effect of, “Come back safe.” There’s no disputing that law enforcement is a dangerous occupation.6 Police officers feel this acutely, but they question whether the public truly understands the risks they face on the job. The vast majority of police (84%) say they worry about their safety at least some of the time, and roughly the same share (86%) say they don’t think the public understands the risks and challenges they face on the job.

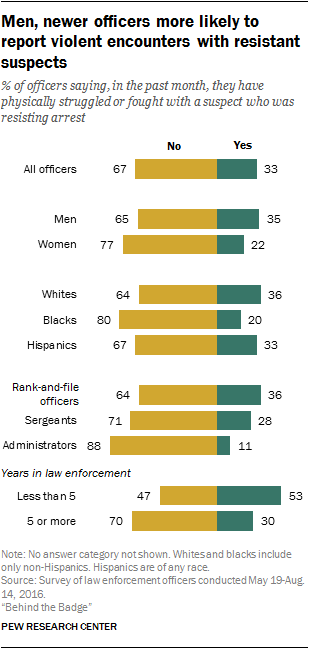

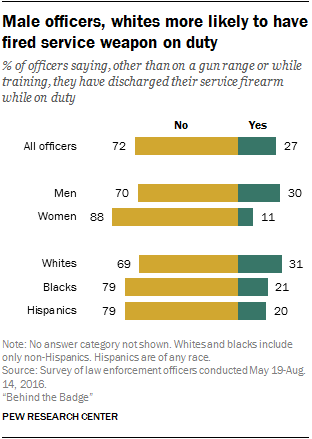

While physical confrontations are not a part of the daily routine for most police officers, a third of all officers say they have struggled or fought with a suspect who was resisting arrest in the past month. Some 27% say they have discharged their service firearm while on duty at some point in their career, not including anytime they used their weapon in training exercises.

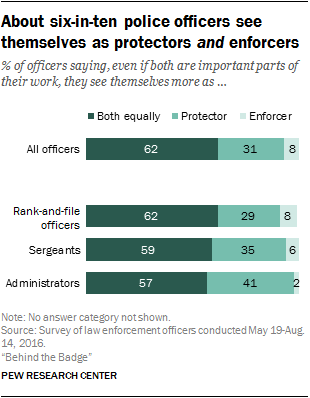

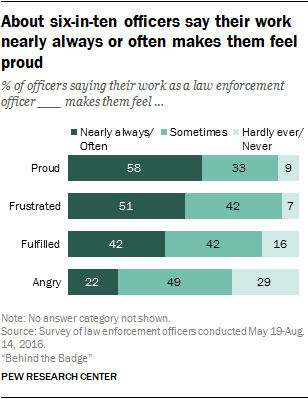

The survey captured the duality of police work on several dimensions. A majority of police (58%) say their work as a law enforcement officer nearly always or often makes them feel proud. But nearly the same share (51%) say their work often makes them feel frustrated. A large majority (79%) say they have been thanked by someone for their police service in the past month, but almost as many (67%) say they have been verbally abused by a member of their community while on duty during that same period. And when asked whether they view themselves more as protectors or enforcers, roughly six-in-ten police officers (62%) say they fill both of these roles equally.

There are significant gaps across key demographic groups on several of these measures. White officers are more likely than black officers to believe that the public doesn’t understand the risks they face on the job, to say they have recently gotten into a physical struggle with a suspect and to say the job makes them feel frustrated or angry. Male and female officers have similar outlooks on their job but report different experiences, especially when it comes to violent confrontations.

Experiences and attitudes also differ substantially according to rank. For example, compared with administrators, rank-and-file officers and sergeants worry more about their safety and feel less understood by the public.

While officers worry about their safety, most feel public doesn’t understand the risks they face

When asked at the most basic level whether they see themselves more as protectors or enforcers, most police officers (62%) say they see themselves filling both roles equally. About three-in-ten (31%) say they see themselves mainly as a protector, while only 8% say they view themselves more as enforcers.

Across gender, racial and age lines, majorities of police officers say they consider themselves both protectors and enforcers. Black officers (69%) are more likely than white officers (59%) to say this, while a somewhat higher share of white officers (32%) than black officers (27%) say they see themselves mainly as protectors. Administrators are somewhat more likely than sergeants or rank-and-file officers to view themselves mainly as protectors.

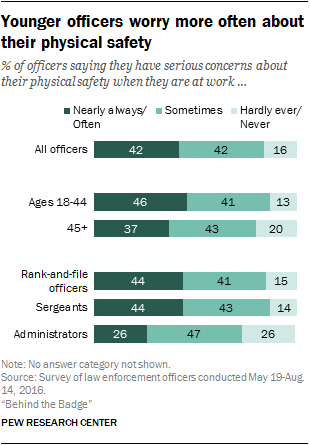

Whether protectors or enforcers, most police officers say that they face dangers on the job. Roughly four-in-ten say that they nearly always (13%) or often (29%) have serious concerns about their physical safety when they are at work. Another 42% say they sometimes have these concerns. Only 16% say they hardly ever or never worry about their safety.

Male and female officers report having serious concerns about their safety with roughly equal frequency. And there are only modest differences on this measure between black and white officers.

Younger officers express a higher level of concern about their safety than do their older counterparts. Among those ages 18 to 44, fully 46% say they nearly always or often have serious concerns about their physical safety when they are at work; 37% of officers ages 45 and older voice the same level of concern.

Perhaps related to the age differences or their specific job assignments, rank-and-file officers and sergeants are more likely than administrators to say they often have concerns about their safety.

The level of concern on the part of individual officers did not appear to increase after the fatal attack on five officers in Dallas last summer. The share of police saying they nearly always or often have serious concerns about their own safety remained fairly consistent pre-Dallas to post-Dallas.

While not commonplace, physical confrontations with suspects are not a rare occurrence for police

A third of all officers say they have physically struggled or fought in the past month with a suspect who was resisting arrest. There are large demographic differences on this measure. Male officers are much more likely than their female counterparts to report having had this type of encounter in the past month – 35% of men vs. 22% of women.

There are large gaps by race as well. While 36% of white officers say they have struggled or fought with a suspect in the past month, only 20% of black officers say they have had the same type of experience. Among Hispanic officers, 33% say they had an encounter like this. These racial patterns persist across different-sized agencies.

Officers who are fairly new to the job are much more likely than more seasoned officers to have struggled or fought with a suspect in the past month. Some 53% of officers who have been on the job for less than five years say they have done this, compared with 30% of those who have been on the job five years or longer.

These experiences also vary significantly by rank. Among rank-and-file officers, 36% say they have had a violent encounter with a suspect who was resisting arrest in the past month; 28% of sergeants report having a run-in like this, as do 11% of administrators.

Perhaps not surprisingly, police who have had this type of experience recently are more likely than those who have not to say they often have serious concerns about their personal safety when they are on the job (54% vs. 37%).

About seven-in-ten officers have never fired their service weapon while on duty

Most officers say that, outside of required training, they have not discharged their service firearm while on duty; 27% say they have done this. Male officers are about three times as likely as female officers to say they have fired their weapon while on duty – 30% of men vs. 11% of women.

Among white officers, 31% say they have discharged their service firearm while on duty. A smaller share of black (21%) and Hispanic (20%) officers report doing the same.

Not surprisingly, officers with a longer tenure in law enforcement are more likely than newer officers to have used their firearm while on duty. Some 14% of those with less than five years of experience say they have fired their weapon, while 29% of officers who have been on the job five years or longer say they have done this. Interestingly, those with 20 or more years of experience are no more likely than those with 10 to 19 years of service to have used their weapon while on duty.

How well does the public understand the risks police face? Four-in-ten officers say not well at all

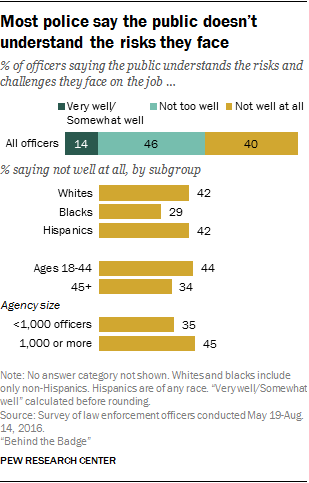

The relationship between the police and the public is a complicated one. While many police officers often worry about their own safety, the vast majority believe the public doesn’t understand the risks and challenges they face on the job. When asked how well the public understands the risks police face, 46% of officers say not too well, and an additional 40% say not well at all. Only 1% say the public understands the risks and challenges faced by police very well, and 12% say the public understands somewhat well.

White and Hispanic officers are much more likely than black officers to say the public doesn’t understand the risks and challenges involved in police work. Fully 42% of white and Hispanic officers say the public does not understand these risks well at all, compared with only 29% of black officers.

Younger officers are more skeptical than their older counterparts that the public grasps the risks and challenges police face on the job. While 44% of officers ages 18 to 44 say the public doesn’t understand these things well at all, only 34% of officers ages 45 and older agree with this assessment. Similarly, rank-and-file officers (42%) and sergeants (39%) are more likely than administrators (25%) to say the public doesn’t understand police work well at all.

Officers from larger departments feel more of a disconnect with the public than officers from smaller departments. Among those in departments with 1,000 or more officers, 45% say the public doesn’t understand well at all the risks and challenges police face. Among those in departments with fewer than 1,000 officers, 35% share this view.

For police, contact with citizens can be a mixed bag

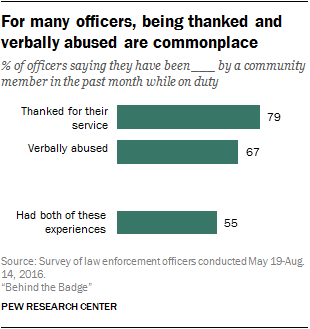

Police interact with the public in a variety of settings, and the reaction they get from community members can range from affirmative to abusive. About eight-in-ten officers (79%) say they have been thanked by a community member for their police service in the past month. At the same time, 67% say they have been verbally abused by a member of their community while they were on duty over the same period.

In some ways, these two common experiences sum up the complex nature of policing: Praise and hostility can both be part of a typical day’s work. Fully 55% of officers say they have had both of these experiences over the past month.

The experience of being thanked by a community member tends to be fairly universal. Large majorities of officers across most major demographic groups report that they have been thanked for their service in the past month. The share of Hispanic officers reporting this (73%) is somewhat lower than the share of white (81%) or black (83%) officers.

Officers who are relatively new to the job are more likely to report being thanked in the past month: 92% of officers who have been on the job less than five years say this, compared with 77% of those who have been on the force five years or longer.

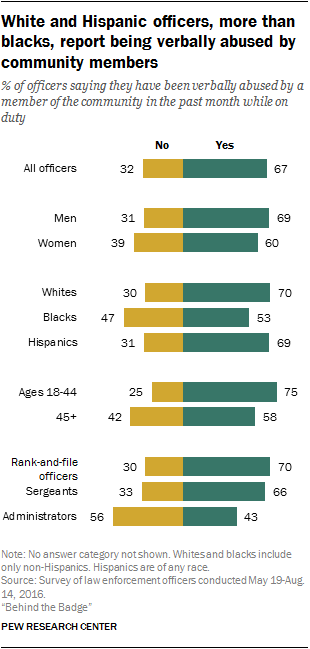

When it comes to being verbally abused by community members while on duty, male officers report having had this experience more often than their female counterparts: 69% of men say they’ve had this type of experience in the past month, compared with 60% of women.

The gap between black officers and their white and Hispanic counterparts is even wider: Seven-in-ten white officers and roughly the same share of Hispanic officers (69%) say they have been verbally abused by a community member in the past month, while 53% of black officers report the same. In addition, younger officers are more likely than older officers to have had this type of encounter – 75% among officers ages 18 to 44 vs. 58% among those ages 45 and older. Administrators, who have less day-to-day contact with community members, are significantly less likely to say they have been verbally abused in the past month. Even so, 43% of administrators say they have had this type of experience.

Roughly three-in-ten officers say they’ve spent at least 30 consecutive minutes patrolling on foot in the past month

The image of the “cop walking the beat” is not necessarily the norm for today’s police. Among all officers, regardless of rank or assignment, roughly three-in-ten officers (31%) say they have patrolled on foot continuously for 30 minutes or more in the past month; 68% say they have not done this.

Among officers who say their current job responsibility is patrolling (45% of all police), 39% say they have patrolled on foot for 30 minutes or more in the past month. Within this group, similar shares of men and women say they have patrolled on foot in the past month. And younger and older patrol officers are about equally likely to have done this.

The prevalence of patrolling on foot doesn’t differ significantly by community type – similar shares of patrol officers from urban (39%) and suburban (38%) departments say they have patrolled on foot for at least 30 continuous minutes in the past month.

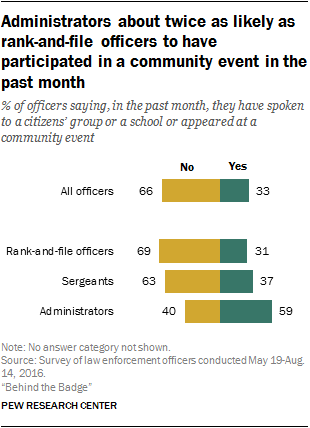

To be sure, there are many ways – beyond walking the streets – for officers to engage with their communities. A third of all officers say they have spoken to a citizens’ group or a school or appeared at a community event in the past month. Where administrators are less likely than officers to patrol the streets, they are about twice as likely to appear at community events. Among rank-and-file officers, 31% say they have done this in the past month. By comparison, 59% of administrators (and 37% of sergeants) have appeared at a community event.

Police from larger agencies (1,000 officers or more) are less likely than those from agencies with fewer than 1,000 officers to have spoken to a citizens’ group or participated in a community event (28% vs. 38%). Black officers are somewhat more likely than white officers to have done this (42% vs. 32%).

Police say they feel pride in their work more often than fulfillment

Police express a range of emotions when asked how their work makes them feel. Pride is a common sentiment, but so is frustration. A majority of all officers say their work in law enforcement nearly always (23%) or often (35%) makes them feel proud. About half say their work nearly always (10%) or often (41%) makes them feel frustrated.

To some degree, pride and frustration are negatively correlated. Among the small share of officers who say their work as a police officer hardly ever or never makes them feel proud, the vast majority (90%) say they nearly always or often feel frustrated by their work. Among those who nearly always or often feel pride in their work, only 37% also say they regularly feel frustrated by their job.

Roughly four-in-ten officers say their work makes them feel fulfilled nearly always (9%) or often (33%), while about half as many say their work makes them angry (3% nearly always, 19% often).

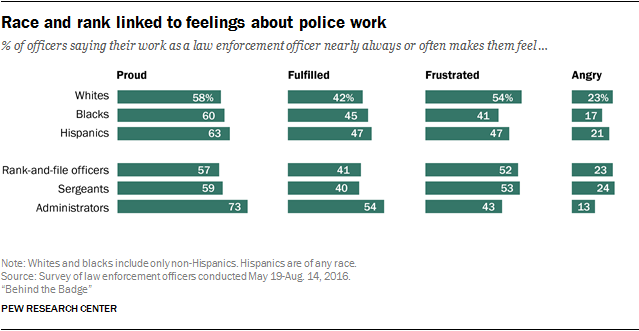

Feelings about police work vary significantly across key demographic groups. White officers are significantly more likely than black officers to say they nearly always or often feel frustrated by their work. Some 54% of white officers say this, compared with roughly four-in-ten (41%) black officers. Hispanic officers fall in the middle on this measure.

About one-in-four white officers (23%) say their work in law enforcement nearly always or often makes them feel angry. A smaller share of black officers – 17% – say this. Among Hispanic officers, 21% say they nearly always or often feel angry, a share that is not significantly different from white or black officers.

When it comes to positive feelings about police work, white, black and Hispanic officers are more closely aligned. Similar shares of each group of officers say their work in law enforcement nearly always or often makes them feel proud and fulfilled (though the share of Hispanic officers who feel this way is slightly higher than the share of whites).

Police officers who are new to the job are more likely than more seasoned officers to say their work makes them feel proud or fulfilled, and they are less likely to say they often feel frustrated. Seven-in-ten officers who have been on the job less than five years say they nearly always or often feel proud of the work they do. By comparison, 57% of those who have been on the job five years or more say they always or often feel proud. Similarly, 59% of new officers say their work makes them feel fulfilled nearly always or often, a sentiment shared by 40% of officers who’ve been on the force for five years or more. And while 39% of new officers say they nearly always or often feel frustrated by their job, 53% of those with five or more years on the force say this.

There are sharp gaps by rank in the emotions officers experience on the job. Administrators (73%) are much more likely than rank-and-file officers (57%) or sergeants (59%) to say they nearly always or often feel proud of the work they do. Administrators also say they more often feel fulfilled by their job: 54% of administrators vs. 41% of rank-and-file officers and 40% of sergeants say their work nearly always or often makes them feel fulfilled.

In addition, administrators are less likely to voice frustration or even anger over their jobs. While 43% of administrators say their job nearly always or often makes them feel frustrated, about half of rank-and-file officers (52%) and sergeants (53%) say they often feel this way. Rank-and-file officers (23%) and sergeants (24%) are roughly twice as likely as administrators (13%) to say their work nearly always or often makes them feel angry.

For police, sometimes moral imperative trumps department rules

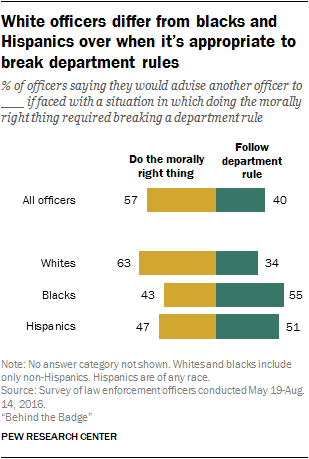

Sometimes police are faced with situations where doing what is morally the right thing would require breaking a department rule. By a ratio of 57% to 40%, officers say they would advise a fellow officer in this type of situation to do the right thing rather than follow the rule.

The balance of opinion on this question is fairly consistent across major demographic groups, with one exception. White officers have a much different view on this than their black and Hispanic counterparts.

Among white officers, 63% say they would advise another officer to do the morally right thing, even if it requires breaking a department rule. Only 43% of black officers and 47% of Hispanic officers say the same. Among black officers, 55% say they would advise a fellow officer to follow the department rule.

Views on this hypothetical dilemma vary only modestly across rank and job tenure. Rank-and-file officers, sergeants and administrators all lean narrowly toward advising a fellow officer to do the morally right thing even if it requires breaking a department rule. Administrators are slightly more likely than the rank and file to say this.

Officers who work in urban departments (60%) are somewhat more likely than those working in suburban departments (53%) to say they would advise a colleague to do the morally right thing even if it meant breaking the rules.

Police were also asked about the extent to which the so-called code of silence prevails in their department when someone witnesses wrongdoing or unethical behavior by a fellow officer. Respondents were asked to imagine a scenario in which an officer who is on duty is driving his patrol car on a deserted road and sees a vehicle that is stuck in a ditch. The officer discovers that the driver is a fellow officer who is not hurt but is obviously intoxicated. Instead of reporting the accident and the offense, he drives the intoxicated officer home. (The scenario did not include any information about the potential punishment for the intoxicated officer.)

After being presented with this set of facts, roughly half (53%) of the officers surveyed said that most officers in their department would not report the officer who covered up for his colleague, including about a quarter who say only a few (22%) or none (5%) of their peers would report the cover-up.

On the flip side, roughly three-in-ten officers (29%) surmised that all or most of the officers in their department would turn in the officer who covered up. Some 15% said about half of the officers in their department would turn in their colleague.