Shortly after noon on Aug. 9, 2014, Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black man, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. Since 2015, almost 500 blacks have been fatally shot by police.11 Their deaths and the disputed circumstances surrounding many of these incidents have sparked widespread protests over police tactics and raised new questions about the relationship between the black community and the police.

A large majority of officers view these protests with deep skepticism. Fully two-thirds of police (68%) say the demonstrations are motivated to a great extent by long-standing bias against the police. A similarly sized majority (67%) characterizes the deaths of blacks during encounters with the police that prompted these demonstrations as isolated incidents and not signs of a broader problem between police and the black community. Black and white officers have profoundly different views on this issue: 57% of black officers but only 27% of their white colleagues say these deadly incidents point to larger issues between blacks and police.

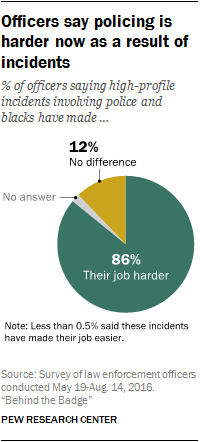

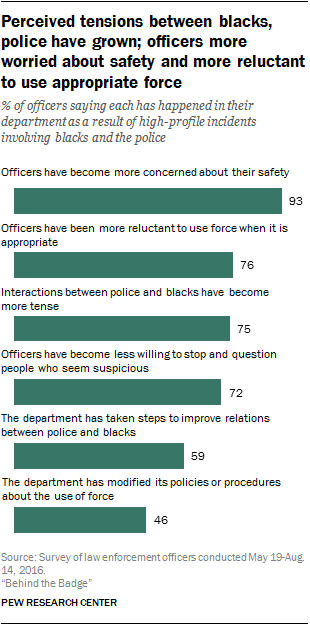

At the same time, these fatal encounters and the public outcry they have generated have affected police work in fundamental ways. More than eight-in-ten officers say their job is harder now as a result of these incidents. Three-in-four officers say interactions between police and blacks in their community have grown more tense. About as many (72%) also say their colleagues are less willing now to stop and question people who seem suspicious or to use force when it is appropriate to do so.

Roughly nine-in-ten (93%) also say officers in their departments are now more concerned about their safety, an assessment the overwhelming majority of officers held even before the ambush slayings of five Dallas police officers on July 7, 2016, by a black man who reportedly sought to avenge recent shootings of black men by police.

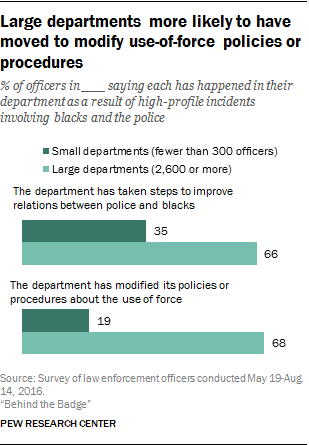

These incidents also have prompted many police departments to examine their own use-of-force policies, the survey finds. About half of officers (46%) report that their department has modified its use-of-force policies or procedures, including 68% of officers in agencies with 2,600 or more sworn personnel. About six-in-ten officers (59%) say their agency has taken steps to improve relations between police and blacks.

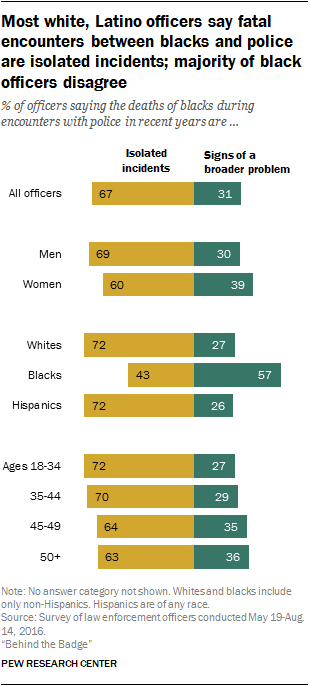

Large majority of officers say fatal encounters are isolated incidents

Two-thirds of police officers (67%) say the highly publicized deaths of blacks during encounters with the police are isolated incidents, while 31% describe them as signs of a broader problem. Moreover, the survey finds that majorities of officers in virtually every major demographic group share this view, with one striking exception. A majority of black officers (57%) say these deaths are evidence of a broader problem between police and blacks, a view held by only about a quarter of all white (27%) and Hispanic (26%) officers.

Black female officers in particular are more likely to say these incidents signal a more far-reaching concern. Among sworn officers, 63% of black women say this, compared with 54% of black men. By contrast, roughly equal proportions of white male officers (27%) and white female officers (29%) say the same. Among Hispanic officers, about a quarter of men (26%) and 32% of women say the incidents reflect a broader problem.

Less dramatic differences arise between other demographic groups. Overall, male officers are more likely than female officers to see these deadly encounters as isolated incidents (69% vs. 60%, respectively), in large part because disproportionately more black women say these incidents point to a more pervasive problem.

Younger police also are more likely than older officers to say these fatal police-black encounters are isolated incidents, a view shared by 72% of officers younger than 35 but 63% of officers 50 and older. Similarly, larger shares of rank-and-file officers and sergeants view these deaths as isolated incidents (68% and 69%, respectively), compared with 61% of administrators.

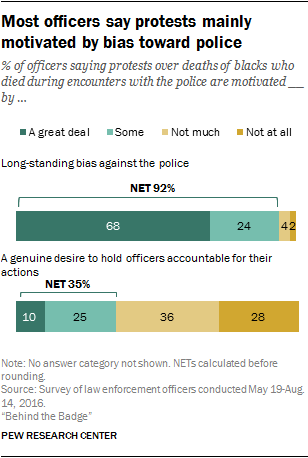

Most officers say anti-police bias motivates protests

Overall, a majority of officers are deeply skeptical of the motives behind those who are protesting high-profile deaths of blacks at the hands of police. However, black officers are far more likely than their white colleagues to believe that protests are motivated by a desire to hold officers accountable.

Overall, about nine-in-ten officers (92%) say long-standing anti-police bias is a motive for the protests, comprising 68% who say it is a great deal of the motivation and about a quarter (24%) who believe bias plays some role. Only 7% say bias against the police is not much or not at all a reason for the protests.

At the same time, only about a third (35%) say protesters felt a genuine desire to hold officers accountable for their actions, including 10% who say a great deal of the motivation for the protests arises from the desire for accountability. By contrast, about two-thirds say the desire for accountability was not much (36%) or not at all (28%) a motive for the protesters’ actions.

Overall, at least nine-in-ten officers across racial/ethnic groups – 95% of whites, 91% of blacks and 90% of Hispanics – say the protests are motivated at least to some extent by anti-police bias. But white officers are more likely than black officers to say protests are driven a great deal by bias against the police (72% vs. 59%, respectively). About two-thirds of Hispanic officers (65%) share this view, placing them squarely between whites and blacks.

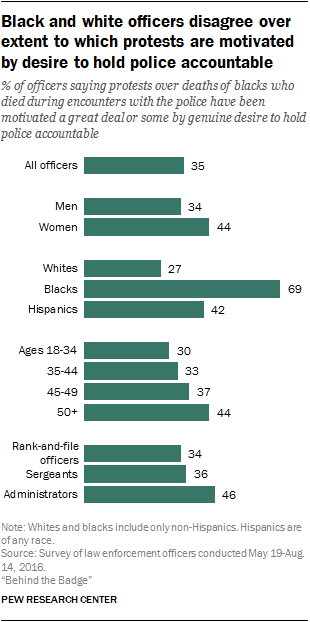

The racial and ethnic divide among officers opens even wider when they are asked the degree to which protesters are motivated by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions. A substantial majority of black officers (69%) say the desire for accountability was a great deal (34%) or some (35%) of the impetus for the protests.

By contrast, about a quarter of white officers (27%) say this, including only 5% who say it had a great deal to do with the demonstrations. Again, Hispanic officers (42%) fall between whites and blacks on this question.

Differences also emerge when the focus shifts to gender, age and officer’s rank. Among all sworn officers, women are significantly more likely than men to say the protests are, at least to some extent, efforts to produce accountability (44% vs. 34%).

Younger and older officers also hold significantly different views. According to the survey, three-in-ten officers younger than 35 say the desire for accountability is motivating the demonstrators a great deal or some. By contrast, 44% of officers 50 years old or older say this.

Police administrators are more sympathetic to the motives of protesters than lower-ranking officers. Fully 46% of administrators say demonstrators are motivated a great deal or some by the desire to make police accountable for their actions. By contrast only about a third of rank-and-file officers (34%) and sergeants (36%) share this view.

Officers say high-profile incidents have made policing harder

Police work is a hard job that most officers say has become harder as a result of deaths of blacks who died during encounters with police. Across every major demographic group analyzed for this survey, about eight-in-ten officers or more say these high-profile incidents have made policing more challenging and more dangerous.

Overall, fully 86% of officers say their job is harder now as a result of these deadly encounters. Even officers from smaller departments that typically serve smaller communities say it’s harder to be a police officer now; 84% of police in departments with fewer than 300 sworn officers say their job is more difficult now – and so do 89% of officers in big-city departments with 2,600 or more police.

An officer’s race matters, though not as much on this question as in others in this survey. Roughly nine-in-ten white officers (89%) say policing is now harder, compared with 81% of black officers. Among all sworn officers, black male officers in particular are significantly less likely than either white men or women to say their job is harder now (79% for black men vs. 89% and 90% for white men and women, respectively). Among black female officers, 84% say their job is more difficult now.

Officers say policing has changed

To measure the impact of fatal police-black encounters on police work, the survey asked officers if their department has changed in six possible ways as a result of these high-profile incidents involving blacks and the police. The results document a range of consequences in departments across the country.

- Increased safety concerns: Fully nine-in-ten officers (93%) say police in their department have become more concerned about their safety. An analysis of survey responses taken before and after five police officers died in an ambush-style attack by a gunman in Dallas suggests that safety worries were high even before this incident: About nine-in-ten (92%) officers expressed concerns about their physical safety before the attack, compared with 97% after the attack, a small but significant increase.

- Increased reluctance to use force: As a result of high-profile fatal police-black encounters, three-quarters of officers (76%) say officers in their department have been more reluctant to use force when it is appropriate. White and Hispanic officers (76% and 81%, respectively) are more likely than black officers (68%) to say their colleagues are holding back in using more forceful methods, even when such tactics are suitable for the situation.

-

Increased tension between police and blacks: Three-quarters of all officers report increased tension between blacks and police in their community. Female officers are somewhat more likely than males to say this (80% vs. 75%).

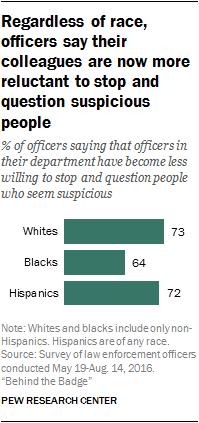

- Increased reluctance to stop and question suspicious people: About seven-in-ten officers (72%) say the widely publicized deaths of blacks who died during encounters with police have made officers in their department less willing to stop and question people who seem suspicious. This finding raises the possibility that many officers are responding to these incidents by “de-policing” – that is, by not fully carrying out their law enforcement responsibilities out of fear of becoming involved in a high-profile incident. 12 A larger share of white police officers (73%) than black officers (64%) say their colleagues are now more hesitant to question suspicious people. In particular, white male officers are significantly more likely to say this (74%) than white female or black male officers (65% for both).

At the same time, the survey finds that many departments have initiated or modified programs to address issues raised by the fatal encounters between blacks and police.

- Efforts to improve black-police relations: About six-in-ten officers (59%) say their department has taken steps to improve relations with the black community. This view varies substantially by the rank of the officer. Roughly eight-in-ten department administrators (79%) say their department has initiated outreach efforts to the black community. By contrast, only 56% of rank-and-file officers and 64% of sergeants express a similar view, suggesting that word about such efforts may not be filtering down the ranks.

-

Changes to the department’s use-of-force policies and procedures: Roughly half of all officers (46%) say their departments have modified their use-of-force protocols as a consequence of fatal black-police encounters. Black officers are more likely than whites to say this change has happened in their department (59% vs. 42% for whites).

Larger departments most affected

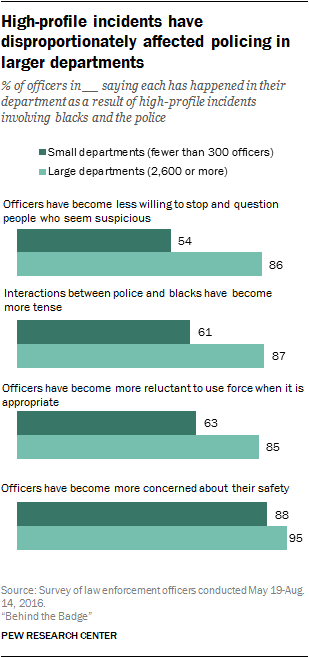

The series of high-profile deadly incidents involving police and blacks has had the greatest impact on officers in the country’s largest police departments.

On every measure tested, police working in departments with 2,600 sworn officers or more are significantly more likely to say their department has been affected by these incidents than those in police agencies with fewer than 300 officers. Among departments with more than 100 sworn police, three-in-ten officers nationally work in these large departments, while a slightly smaller share are employed in agencies with fewer than 300 officers (24%). The others work in departments with 300 to 2,599 officers (45%).

About nine-in-ten officers (86%) in large departments with at least 2,600 officers say their colleagues have become less willing to stop and question suspicious individuals. By contrast, about half (54%) in small departments with fewer than 300 officers say this.

Fully 87% of officers in large departments, but 61% in small agencies, say relations with blacks in their community have grown more tense as a consequence of recent black deaths during encounters with the police. Some 85% of officers in large police departments say their colleagues are more reluctant now to use force even when it is appropriate to do so. By contrast, about six-in-ten (63%) in small departments say this.

On just one measure are there only modest differences between police in larger and smaller departments: Fully 95% of officers in the largest departments say police are now more concerned about their safety, a view shared by 88% of those in small agencies.

Equally striking differences between larger and smaller departments emerge when officers were asked if their department has taken steps to improve relations between police and the black community.

About two-thirds of officers in large departments (66%) say their department has attempted to improve relations between officers and the black community as a result of fatal police-black encounters, while 35% of the officers in small departments say the same.

Similarly, about two-thirds of officers in larger departments (68%) say their department has modified its use-of-force rules in response to fatal police-black encounters, while 19% of the officers in small departments say the same.