Jump to a section of this report:

A growing share of working parents and an aging population have put pressure on more American workers as they balance family caregiving responsibilities and work obligations. Amid these changes, the issue of paid family and medical leave has captured the attention of policymakers and advocates across the political and ideological spectrum.

A new study conducted by Pew Research Center finds that Americans largely support paid leave, and most supporters say employers, rather than the federal or state government, should cover the costs. Still, the public is sharply divided over whether the government should require employers to provide this benefit or let employers decide for themselves, and relatively few see expanding paid leave as a top policy priority.

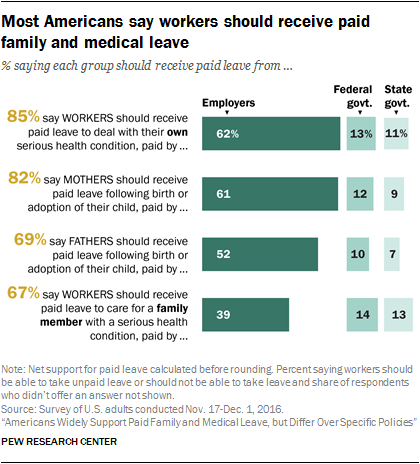

While majorities of adults express support for paid leave for mothers and fathers after the birth or adoption of their child, as well as for workers who need to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own medical issues, support is greater in some cases than in others. About eight-in-ten Americans (82%) say mothers should have paid maternity leave, while fewer (69%) support paid paternity leave. And those who favor paid maternity and paternity leave say mothers should receive considerably more time off than fathers (a median of 8.6 weeks off for mothers vs. 4.3 weeks for fathers).

There is also broader support for paid leave for workers dealing with their own serious health condition (85% say workers should be paid in these situations) than there is for those caring for a family member who is seriously ill (67% favor paid leave for these workers).

The wide-ranging study of public attitudes about paid family and medical leave also included nearly 6,000 interviews with Americans who have recently taken leave (or were unable to take leave when they needed or wanted to do so), in order to reflect direct personal experiences as well as policy views. The survey finds that 64% of those who took leave in the past two years say they received at least some pay during their time off. A large majority of them (79%) say that some or part of that pay came from vacation days, sick leave or paid time off (PTO) they had accrued prior to their leave. Only 20% of those who got paid – or 13% of all “leave takers” – say they had access to family and medical leave benefits paid by their employer.

Note on terminology

Throughout this report, when referring to attitudes toward paid leave policies, the terms “family and medical leave” or leave from work for “family or medical reasons” refer to time off following the birth or adoption of one’s child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with one’s serious health condition.

In order to distinguish between the experiences of those who took time off from work (or who needed or wanted to take time off but were unable to do so) under different circumstances, the term “parental leave” refers to taking time off from work following the birth or adoption of a child; “family leave” refers to taking at least five days off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition; and “medical leave” refers to taking at least five days off from work to deal with one’s own serious health condition.

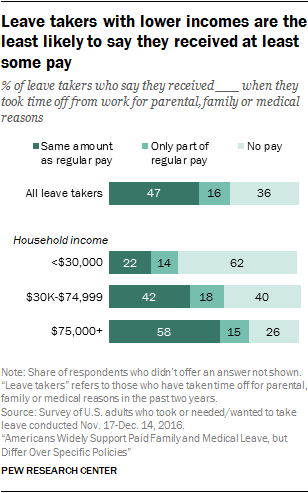

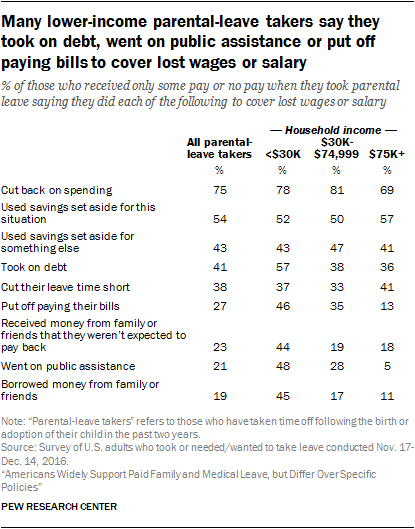

The study reveals a sharp income divide in the way workers navigate these situations. Middle- and higher-income leave takers are much more likely than their lower-income counterparts to have access to paid time off – whether through a specific employer-provided paid leave benefit or by using accrued time off. Six-in-ten leave takers with household incomes between $30,000 and $74,999, and an even higher share (74%) of those with incomes of $75,000 or more, say they received at least some pay when they took time off from work for family or medical reasons. In contrast, only 37% of leave takers with annual household incomes under $30,000 say they received pay. Many lower-income leave takers say they faced difficult financial tradeoffs during their time away from work, including 48% among those who took unpaid or partially paid parental leave who say they went on public assistance in order to cover lost wages or salary.

The need for family and medical leave – whether paid or unpaid – is broadly felt across the United States. Roughly six-in-ten Americans (62%) say they have taken or are very likely to take time off from work for family or medical reasons at some point. Among adults who have been employed in the past two years, about a quarter (27%) say that they took time off during this period following the birth or adoption of their child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with their own serious health condition. In addition, 16% of Americans who were employed in the past two years report that there was a time during this period when they needed or wanted to take time off from work but were unable to do so.

Those who weren’t able to take leave when they needed or wanted to tend to be among the nation’s lower-income workers. Among adults employed in the past two years with annual household incomes under $30,000, three-in-ten say they were unable to take leave when they needed or wanted to at some point in the past two years. By comparison, only 14% of those with incomes of $30,000 or more fall into this category. Across income groups, those who didn’t take time off when they needed or wanted to cite financial concerns more than any other reason when asked why they didn’t take time off from work when they needed or wanted to; about seven-in-ten (72%) say they couldn’t afford to lose wages or salary. This is also the reason cited most often by those who were able to take some time off but wish they had taken more.

These findings are based on two nationally representative online surveys conducted by Pew Research Center with support from Pivotal Ventures: one a survey of 2,029 randomly selected U.S. adults conducted Nov. 17-Dec. 1, 2016, and the other a survey of 5,934 randomly selected U.S. adults ages 18 to 70 who have taken – or who needed or wanted but were unable to take – parental, family or medical leave in the past two years, conducted Nov.17-Dec.14, 2016. 1

The study also finds that adults who are employed or looking for work value flexibility as much as they value having paid family or medical leave. When asked what benefits or work arrangements help them most or would help most personally, about as many cite being able to choose when they work their hours (28%) as cite having paid family or medical leave (27%); about one-in-five (22%) say having flexibility to work from home would help them the most.

However, among those who have taken leave in the past two years or have needed or wanted to do so, having paid leave for family or medical reasons is cited as being the most helpful more than any other benefits or work arrangements. About four-in-ten (38%) in this group point to paid family or medical leave, while the second-most cited item – having flexibility to choose their schedule – is seen as most helpful by 24% of those who have taken leave or needed or wanted to do so in recent years.

The changing demographic landscape in the U.S.

The long-term rise in U.S. women’s labor force participation, particularly among mothers, has led to an increasing share of infants living in homes where all parents are working. In 2016, 50% of children younger than 1 year of age were living in such an arrangement – 40% with two working parents and 10% with a single working parent. Thirty years earlier, this share was 39%; and in 1976, just 20% of infants were living in a home where all parents were working.

Meanwhile, as the elderly population in the U.S. continues to grow, the number of people involved in informal caregiving of older adults is expected to rise. About 15% of the population was ages 65 or older in 2015, and projections suggest that by 2050 about one-in-five (22%) Americans will fall into this category. These older people are more likely to be employed than in the past; in 2016 almost one-in-five people ages 65 or older were still working, up from 12% in 1980, according to Pew Research Center analysis of Current Population Survey data.

In recent years, 25 million working people reported that they provided unpaid care to someone with an aging-related condition in the previous three to four months – 16% of the employed civilian population in the U.S., according to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) American Time Use Survey data. And for some people family caregiving is a multigenerational endeavor. A 2015 Pew Research Center survey found that about half (47%) of adults ages 40 to 59 had at least one parent ages 65 or older, and were also either raising a child younger than 18, or had given financial support to an adult child in the past year.

More than ever, caregiving responsibilities extend to both women and men. While in 1965 married fathers living with their children spent about 2.5 hours a week on child care, that number rose to seven hours a week by 2015. In comparison, moms spent about 15 hours a week caring for their child in 2015. And when it comes to providing care for older adults, men and women are similarly likely to have done so in the prior three to four months. Among the employed civilian population, about 15% of men say as much, as do 18% of women, according to the BLS.

Most supporters of paid leave say pay should come from employers rather than from state or federal government

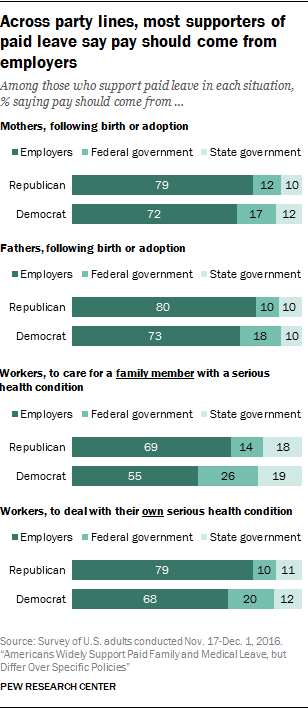

About three-quarters of Americans who support paid leave for mothers (74%) or fathers (76%) following the birth or adoption of a child say pay for time off should come from employers, and a similar share (72%) of those who favor paid medical leave for workers with a serious health condition say the same. When it comes to who should cover the cost of paid leave for workers when they take time off to care for a family member with a serious health condition, a smaller majority (59%) of paid-leave supporters say pay should come from employers, while about two-in-ten say it should come from federal (22%) or state (20%) government.

The majority of paid-leave supporters across the political spectrum are more likely to look to employers rather than to government to cover the costs of providing this benefit, although Democrats express more support for government-paid family and medical leave than do Republicans. For example, about a third (32%) of Democrats who say workers should have paid leave from work to deal with their own serious health condition say pay should come from either the federal or state government, compared with 21% of Republican supporters of paid medical leave. And while 45% of Democrats who support paid leave for workers who take time off to care for a seriously ill family member say the government should pay for this benefit, 31% of Republicans who support paid leave for this reason say the same. More modest but still significant partisan differences are also evident on views of who should pay when mothers and fathers take leave.

Overall, Democrats are more supportive of paid leave than are Republicans and independents, though at least three-quarters of each group say mothers should have access to paid maternity leave and that workers should be able to take paid leave to deal with their own serious health condition. Democrats, Republicans and independents are less supportive of paid leave for fathers and for workers who need to care for a family member with a serious health condition than they are of paid maternity and medical leave. Still, most Democrats and independents – and just over half of Republicans – express support for paid leave in each of these two situations.

Women and young adults also generally express more support for paid leave than do men and those ages 30 and older. For example, 82% of adults ages 18 to 29 say fathers should be able to take paid leave following the birth or adoption of their child, compared with 76% of those ages 30 to 49, 61% of those 50 to 64, and 55% of adults 65 and older.

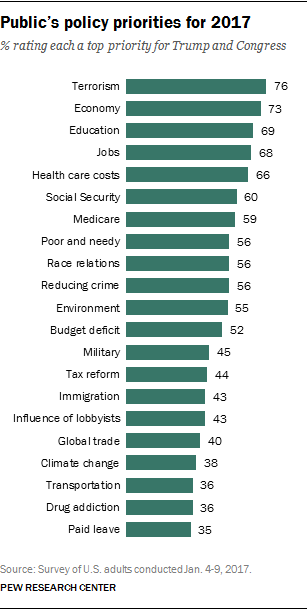

Despite the broad support for paid leave, a Pew Research Center survey conducted Jan. 4-9, 2017, about the public’s policy priorities for President Donald Trump and Congress in the coming year finds that relatively few Americans (35%) see expanding access to paid family and medical leave as a top policy priority. In fact, expanding access to paid family and medical leave ranks at the bottom of a list of 21 policy items, along with improving transportation and dealing with drug addiction.

Most see at least some benefits for employers that provide paid leave

While Americans tend to favor employer-paid over government-paid leave for family or medical reasons, there is no consensus when it comes to a federal government mandate: About as many say the government should require employers to provide paid leave (51%) as say employers should be able to decide for themselves (48%). Opposition to a federal mandate is highest among those who oppose paid leave; among those who support paid family or medical leave, including those who say employers should pay, more say the government should require employers to offer this benefit than say it should be the employers’ decision.

Still, regardless of whether they support a federal government mandate, most Americans think employers stand to benefit from providing paid family and medical leave. About three-quarters (74%) of the public says employers that provide paid leave are more likely than those that don’t to attract and keep good workers; 78% of those who favor a government mandate and 70% of those who say employers should decide for themselves share this view.

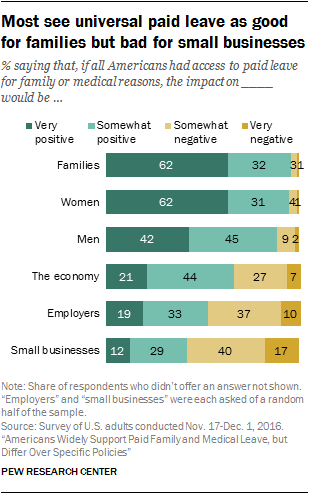

Assessments of the overall impact of paid family and medical leave on employers are more mixed: 53% say universal access to paid leave would have a positive impact on employers, while 46% say the overall impact would be negative. When asked specifically about the impact on small businesses, the balance of opinion is decidedly negative. Roughly six-in-ten Americans (58%) say that universal access to paid leave would have a very or somewhat negative impact on small businesses, while 41% think the impact would be generally positive. By comparison, there is significant consensus around the potential benefits to women and families, with about six-in-ten Americans expecting “very positive” results. Overall, about two-thirds or more say the impact of universal paid leave on families (94%), women (93%), men (88%) and the economy (65%) would be at least somewhat positive.

The public also makes a distinction between employers in general and small businesses in assessments of the trade-offs they may need to make in order to provide paid family and medical leave. About six-in-ten (59%) say most employers that provide paid leave can afford to do so without reducing salaries or other benefits. In contrast, a majority (69%) say most small businesses that offer paid leave have to cut back on salaries and other benefits in order to do so.

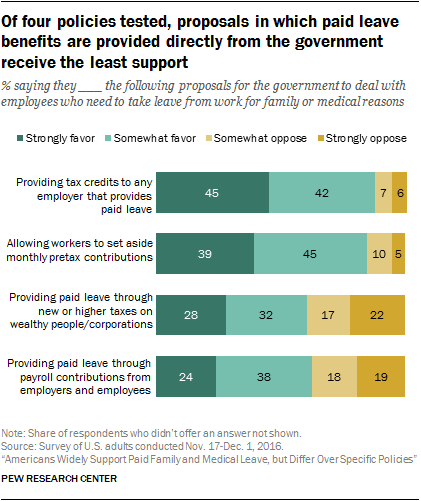

There’s no public consensus on the best policy approach for providing paid family and medical leave. In general, the public has a more positive view of policies that incentivize employers or employees rather than those that create a new government fund to finance and administer the benefit.

Some 45% of Americans say they would strongly favor the government providing tax credits to any employer that provides paid leave. And roughly four-in-ten (39%) express strong support for allowing workers to set aside monthly pretax contributions into a personal account that can be withdrawn if they need to take leave from work.

There is less support for a program where the government would provide paid leave to any worker who needs it using funding from new or higher taxes on wealthy people or corporations – 28% strongly favor this approach. Similarly, 24% strongly favor the establishment of a government fund for all employers and employees to pay into through payroll contributions that would provide paid leave to any worker who needed it.

Support for new government programs that would provide paid family and medical leave to all workers that need it is far stronger among Democrats than among Republicans or independents. Some 44% of Democrats say they would strongly support a government paid leave program funded by new or higher taxes on wealthy people or corporations, compared with about a quarter (24%) of independents and just 11% of Republicans. And while about a third (34%) of Democrats express strong support for a government paid leave fund that all employers and employees would pay into through payroll contributions, smaller shares of independents (20%) and of Republicans (15%) say they would strongly favor this approach.

Democrats are also more likely than Republicans or independents to say they would strongly support the government providing tax credits to employers that provide paid family and medical leave: About half (53%) of Democrats express strong support for this approach, compared with about four-in-ten Republicans (37%) and independents (41%).

The vast majority of Americans (85%) say that, if the government were to provide paid family and medical leave, the benefit should be available to all workers, regardless of their income, rather than being more narrowly targeted to those with low incomes. When it comes to paid parental leave specifically, about three-quarters (73%) believe that if the government were to provide this benefit, it should be available to both mothers and fathers.

About seven-in-ten fathers who take paternity leave return to work within two weeks

Most Americans (63%) believe that mothers generally want to take more time off from work than fathers after the birth or adoption of their child, and more say employers put greater pressure on fathers to return to work quickly (49%) than say mothers face more pressure (18%) or that both face about the same amount of pressure (33%) from employers.

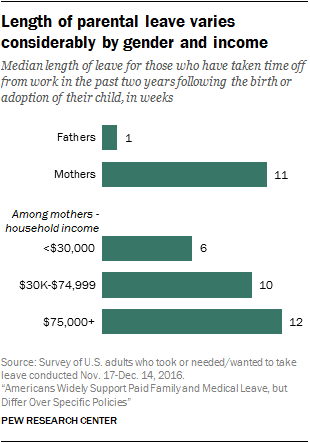

The survey of adults who took leave or who needed or wanted to take leave but weren’t able to do so finds that among fathers who took at least some time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child in the past two years, the median length of leave was one week; about seven-in-ten (72%) say they took two weeks or less off from work. In contrast, the median length of maternity leave was 11 weeks. Among mothers with household incomes under $30,000, however, the median length of leave was six weeks, compared with 10 weeks for those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 12 weeks for mothers with household incomes of $75,000 or more.

For the most part, mothers and fathers who took parental leave in the past two years say taking time off did not have much of an impact – either positive or negative – on their job or career; 60% say this is the case. Still, women are about twice as likely as men to say taking time off following the birth or adoption of their child had a negative impact (25% vs. 13%, respectively).

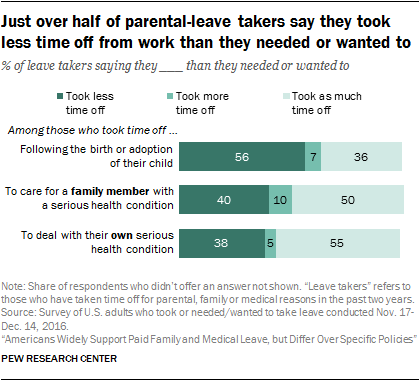

Just over half (56%) of parental-leave takers say they took less time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child than they needed or wanted to, while 7% say they took more time off and 36% say they took about as much time off as they needed or wanted to. Some 59% of fathers and 53% of mothers say they wish they had taken more time off from work than they did following the birth or adoption of their child.

Smaller but substantial shares of those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own health issue also say they took less time off from work than they needed or wanted to take (40% and 38%, respectively).

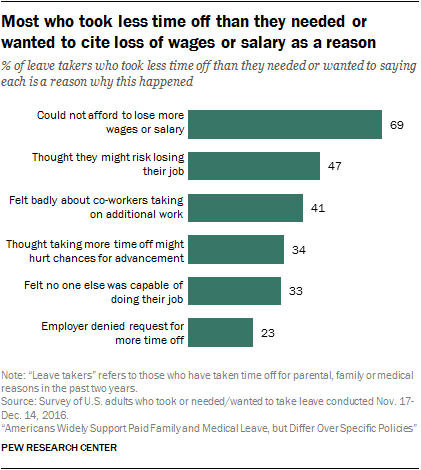

Financial concerns top the list of reasons why those who took leave for parental, family or medical reasons say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to. About seven-in-ten (69%) leave takers who returned to work more quickly than they would have liked to say they couldn’t afford to lose more wages or salary. About half (47%) say they thought they might risk losing their job, while 41% say they felt badly about co-workers taking on additional work. About a third thought taking more time off might hurt their chances for job advancement (34%) or felt that no one else was capable of doing their job (33%). And about a quarter (23%) of those who took less time off than they had needed or wanted to say their employer denied their request for more time off.

Many leave takers take on debt or use savings in order to cover lost wages

Most Americans who took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons report that they received at least some pay during this time, with about half (47%) saying they received full pay; 16% say they received only some of their regular pay and 36% say they received no pay at all. Lower-income leave takers, as well as those without a bachelor’s degree, are particularly likely to say they received only some or no pay. For example, among leave takers with household incomes of $75,000 or more, roughly six-in-ten (58%) say they received the same amount as their regular pay, while 15% received partial pay and about a quarter (26%) were not paid. In contrast, just 22% of those with incomes under $30,000 report that they received full pay, while 14% received only some of their regular pay and a majority (62%) received no pay during their time off from work.

Leave takers who did not receive their full wages or salary when they took parental, family or medical leave say they had to make sacrifices, such as cutting back on spending, dipping into savings, or cutting their leave short, to compensate for the loss of income. Some, particularly those with lower incomes, took more consequential measures, such as taking on debt, putting off paying their bills, and going on public assistance.

Roughly six-in-ten (57%) parental-leave takers with household incomes under $30,000 who did not receive their full pay when they took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child say they took on debt to deal with the loss of wages or salary; about half say they went on public assistance (48%) or put off paying their bills (46%).

Views of gender and caregiving are related to support for paid leave for new fathers

While most Americans are supportive of mothers and fathers taking leave from work – and receiving pay – following the birth or adoption of a child, many see mothers, and women in general, as more apt caregivers. The survey finds that a majority (71%) of Americans think it’s important for new babies to have equal time to bond with their mothers and their fathers, while about a quarter (27%) think it’s more important to bond with their mothers and just 2% say it’s more important for them to bond with their fathers. But when it comes to caring for a new baby, more say that, aside from breast-feeding, mothers do a better job than say both mothers and fathers do about an equally good job (53% vs. 45%); only 1% say fathers do a better job than mothers in caring for a new baby.

The public offers more gender-balanced views when asked who would do a better job caring for a family member with serious health condition – 59% say men and women would do an equally good job. Still, four-in-ten say women would do a better job in this situation (1% say men would).

Older adults and Republicans – especially those who describe their political views as conservative – are particularly likely to say that it’s more important for new babies to have more time to bond with their mothers than with their fathers and that mothers do a better job caring for a new baby.

Attitudes about gender roles and caregiving are linked, at least in part, to views about the impact of paid leave on men, as well as to support for paid paternity leave. Generally, adults with more gender-balanced views about mothers and fathers as caregivers for new babies are far more supportive of paid paternity leave than are those who say mothers are better caregivers. Those with more gender-balanced views are also more likely to say universal paid leave would have a very positive impact on men.

For example, among those who say mothers and fathers do about an equally good job caring for a new baby, 78% express support for paid paternity leave and half say universal paid leave would have a very positive impact on men. By comparison, among adults who say mothers do a better job, these shares are 61% and 37%, respectively. Significant differences remain when controlling for factors such as gender, age and political ideology, which are associated with support of paid leave for fathers and the impact of universal paid leave on men in general as well as with attitudes about gender and caregiving.

The remainder of this report examines in greater detail the public’s views about paid leave as well as the experiences of workers who have taken parental, family or medical leave in the past two years. Chapters 1-4 focus on findings from the survey of the general public. Chapter 1 looks at the public’s evaluations of different paid leave policies, including who Americans think should be covered as well as who should pay. Chapter 2 explores assessments of the impact of paid leave on families, the economy, employers and employees. Chapter 3 looks at workers’ assessments of the benefits they receive from their employers and how family and medical leave fits in to the broader benefits landscape. Chapter 4 explores views of gender and caregiving.

Chapter 5 examines the experiences of those who took leave and those who weren’t able to take leave when they needed or wanted to do so. It looks at whether or not those who were able to take leave received any pay during this time and how they coped with the loss of income if they did not receive full pay. It also explores reasons why some people return to work sooner than they wish to after taking parental, family or medical leave, and why some aren’t able to take time off from work at all when they need or want to do so. Finally, Chapter 6 provides some quotes from eight focus groups of recent parental- and family-leave takers to illustrate the diverse and complex experiences of leave takers.

Other key findings

- Americans express some concern that paid family and medical leave benefits can be abused. Some 55% think it is at least somewhat common for workers who have access to this benefit to abuse it by taking time off from work when they don’t need to; 44% say this isn’t particularly common.

- Most workers are at least somewhat satisfied with the benefits their employer provides (69%) and believe their employer cares a great deal or a fair amount about the personal well-being of their employees (66%). These assessments vary considerably by income, however; only about half of workers with household incomes under $30,000 express some satisfaction with their benefits and say their employer cares about their employees’ well-being, compared with majorities of those with higher incomes.

- Three-in-ten leave takers say it was difficult for them to learn about what leave benefits, if any, were available to them when they needed to take time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons, and this is particularly the case among those with a high school diploma or less and with lower incomes. Leave takers with lower incomes and those without a bachelor’s degree are also less likely to say their supervisor and co-workers were very supportive when they took leave from work.

- Among those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition in the past two years, women (65%) are far more likely than men (44%) to say they were the primary caregiver. Family-leave takers ages 65 and older were more likely than those who are younger to say they were caring for their spouse or partner during this time, while those ages 50 to 64 were particularly likely to be caring for one of their parents.

Throughout this report, when referring to attitudes toward paid leave policies, the terms “family and medical leave” and “taking time off from work for family or medical reasons” refer to taking time off following the birth or adoption of one’s child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with one’s own serious health condition. In order to distinguish between the experiences of those who took time off from work (or who needed or wanted to take time off but weren’t able to do so), the term “parental leave” refers specifically to time taken off from work following the birth or adoption of one’s child; “family leave” refers to taking at least five days off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition; and “medical leave” refers to taking at least five days off from work to deal with one’s own serious health condition.

“Leave takers” refers to those who were employed in the past two years and took time off from work during this time following the birth or adoption of their child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with their own serious health condition. “Paid leave” refers specifically to paid leave for parental, family or medical reasons.

References to whites and blacks include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” refers to those with a two-year degree or those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. “High school” refers to those who have attained a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate.