Those who can’t define democracy are more open to authoritarianism

This Pew Research Center analysis examines how people in Australia and the United Kingdom define democracy. In both countries, respondents were asked the following open-ended question: “In a few words, what does democracy mean to you? What comes to mind when you think about democracy?”

Center researchers then inductively developed a codebook (see Appendix A) for the most commonly referenced themes and topics. All mentions in each open-ended response were then coded by two researchers who had high levels of intercoder reliability on a practice set of responses.

The Australian survey was conducted on the Life in Australia™ panel, created by the Social Research Centre. The survey took place from March 15 to March 29, 2021, with a total of 1,127 panelists. The British survey was conducted on the PUBLIC Voice panel, created by Kantar. The survey took place from March 9 to March 29, 2021, with a total of 2,097 panelists. For more on the Australian methodology, see Appendix B. For more on the British methodology, see Appendix C.

Here is the question used for this report, along with its responses.

Numerous studies have shown that the health of democracy has declined in nations around the world in recent years, and Pew Research Center surveys have found that many citizens are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working and want significant political change.

But what do people mean when they talk about democracy? Are they able to articulate how they think about democracy and are there shared understandings about what it means? A new survey of adults conducted in Australia and the United Kingdom suggests that at least in these two nations, the answer is yes.

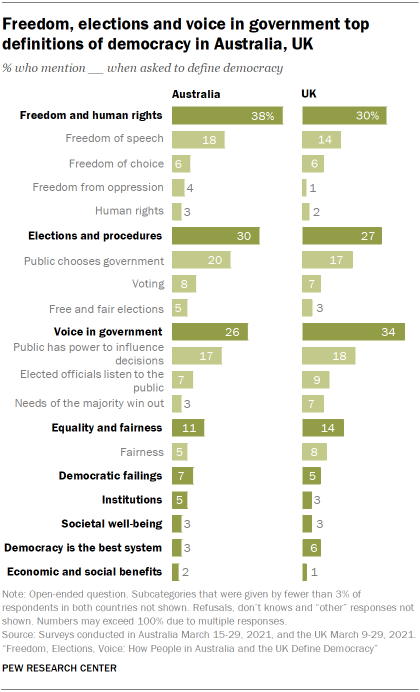

We asked respondents in both countries to, in their own words, define what democracy means to them. Most commonly, people mention three broad concepts: freedom and human rights, elections and procedures, and having a voice in government.

Nearly four-in-ten Australians and three-in-ten Britons mention something related to freedom and human rights. When talking about freedom, respondents discuss many different types of individual liberties, although freedom of speech was mentioned most often. “Democracy means the freedom to speak your opinions without persecution,” said one Australian man.

Only slightly fewer mention things related to elections and procedures, especially the idea that the public gets to choose its leaders in a democracy. People also use language about the act of voting and importance of free and fair elections.

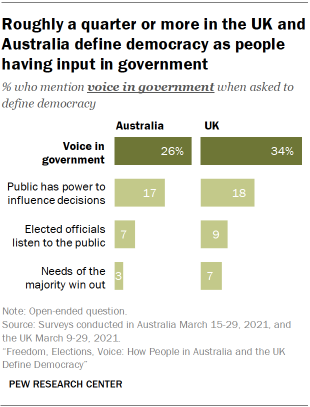

Meanwhile, 26% of Australians and 34% of Britons define democracy with terms that emphasize having a voice in government, in particular the notion that the public has an influence over decisions. The concept of voice is the most frequently mentioned definition in the UK. One British woman declared, “To me, democracy means that elected representatives of the people act in the best interests of those people, not their own interests.”

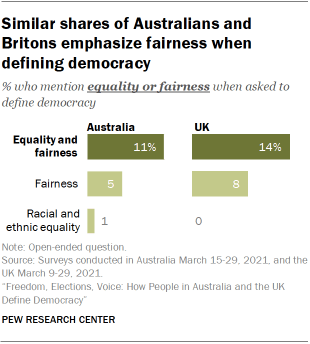

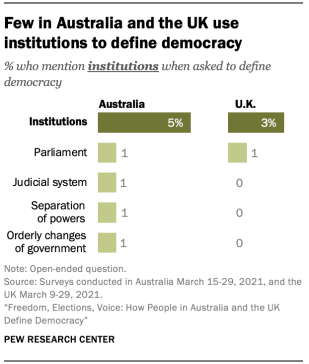

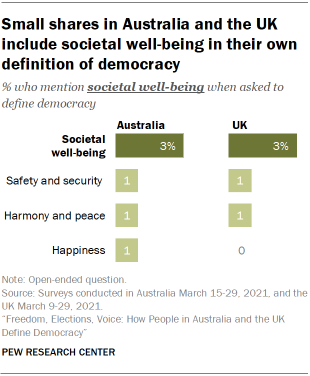

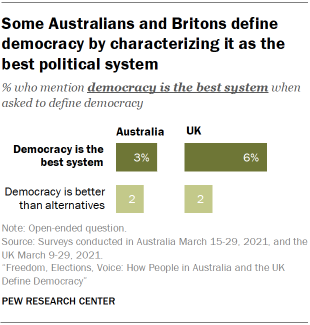

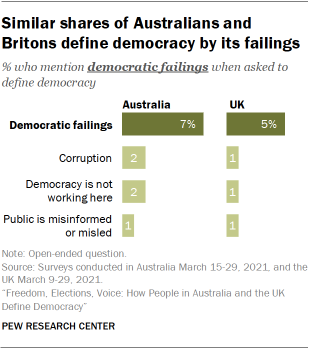

Equality and fairness are less central to public understandings of democracy in these two countries, although double-digit percentages do mention these concepts. Some respondents – 7% in Australia and 5% in the UK – choose to define democracy in terms of its failings, criticizing their political systems and leaders for corruption and a lack of accountability. Fewer still mention specific democratic institutions, societal well-being, economic and social benefits, or that democracy is the best system.

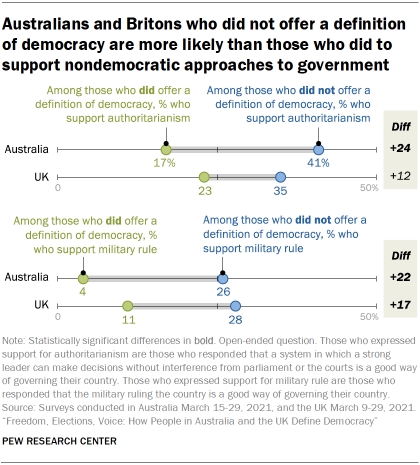

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted from March 9 to 29, 2021, among 3,224 adults in Australia and the UK. The survey also finds that the ability, or inability, to express how you think about democracy is tied to views about authoritarianism. People who do not offer a definition of democracy are also somewhat more open to authoritarian rule.

For instance, among Australians who did give a definition of democracy, 17% say a system in which a strong leader who can make decisions without interference from courts or parliament is a good way to govern the country; among those who did not offer a definition, fully 41% endorse the strong-leader model.

A similar pattern is found on a question about military rule in both countries. Those who do not define democracy on the survey are much more likely to think military rule could be a good political model.

Freedom and human rights

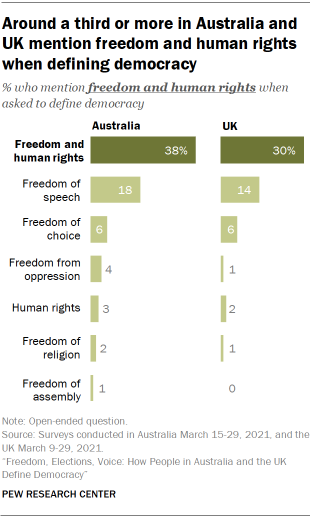

Roughly four-in-ten in Australia (38%) and three-in-ten in the UK (30%) identify freedom and human rights when asked to explain what democracy means to them. In Australia, this topic is the most mentioned among all those coded, while in the UK the topic ranks as the second most cited, behind having a voice in government.

When defining democracy, many simply responded with the word “freedom.” Still, some were more descriptive, as in the case of one Australian woman who responded: “I think it’s freedom, to live a life without a dictatorship and to be happy, plenty of jobs and plenty of availability for Australians to live a normal comfortable lifestyle.”

Among those who brought up this broader topic of freedom and human rights, the largest share in both countries specified freedom of speech when defining democracy (18% in Australia and 14% in the UK).

Freedom of choice is the second most mentioned subset of freedom and human rights in each of the countries surveyed. “Choice is a luxury we’ve earned over years and what drives me to get up each day! Imagine life without choice – rubbish!” said one man in the UK.

Other less frequently mentioned aspects of freedom and human rights include freedom from oppression, human rights, freedom of religion and freedom of assembly.

Older Australians are more likely to mention freedoms and human rights than younger ones. There are no corresponding age differences in the UK.

Supporters of the governing Liberal National Coalition in Australia are also more likely to mention freedoms than supporters of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) or the Greens. In the UK, Liberal Democrats and Conservatives both mention freedoms more often than Labour Party supporters. In both countries, those who place themselves on the right of the ideological spectrum are also significantly more likely to define democracy by invoking freedom and human rights than those on the left.

In Australia, people who mention freedom and human rights in their definition of democracy are somewhat more likely to be satisfied with democracy than those who do not mention this topic (78% vs. 64%, respectively). And those in Australia who define democracy around freedom are significantly more likely to say that rule by a strong leader and rule by experts (and not elected officials) are very bad ways of governing the country.

Elections and procedures

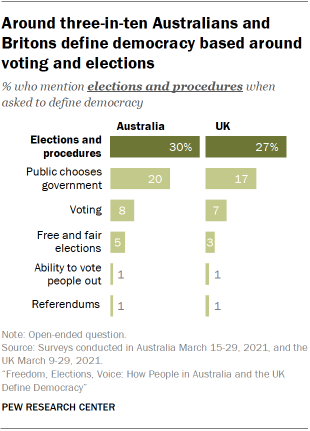

Around three-in-ten in both Australia (30%) and the UK (27%) mention something related to elections and their procedures when defining democracy. The bulk of these definitions center on the public’s role in choosing the government – around two-in-ten in each country focus on the public’s role in selecting representatives. For example, one man in Australia defined democracy as “a system allowing the citizens to decide which group legislates on the day-to-day running of a country.”

Some – 8% in Australia and 7% in the UK – specifically emphasize the act of voting or casting a ballot. One man in the UK described democracy as “citizens vote to elect a governing party for a period of years with opposition parties to question and offer alternative policies.” Slightly fewer in each country also highlight the importance of elections being free or fair as part of their definition, as is the case with one British woman who declared that democracy is “a fair vote, an honest vote.”

“Leaders of the country elected by the citizens in an election that is totally transparent, free and fair.”

–Man, UK

While the relative emphasis is on voting people into office, in both countries, 1% of people specifically mention the ability to use elections to get rid of ineffective leaders. In Australia, one woman noted both in her definition of democracy: “Ability to elect people that represent the views of the community and the ability to vote out people who are not doing a good job.” Similarly, few in both countries specifically mention referendums or direct democracy.

In the UK, those with lower levels of education are somewhat more likely to mention elections and procedures in their definition of democracy than those with higher levels of education. Those who have a favorable view of the right-wing, populist Reform UK (formerly the Brexit Party) are also somewhat more likely to mention the public choosing the government than those who have an unfavorable view of the party. In Australia, those on the ideological left are somewhat more likely to define democracy by mentioning elections and procedures than those on the right.

Australians who define democracy as centered around elections and procedures are somewhat more likely to say that representative democracy is a good way to govern their respective countries. In both places, those who emphasize elections and procedures are less likely to say military rule is acceptable for their country.

Voice in government

Roughly a third of people in the UK (34%) and around a quarter in Australia (26%) define democracy as giving people a voice in government. In the UK, this makes voice in government the most common theme given in defining democracy. In Australia, voice is the third most mentioned theme, behind freedom and human rights and elections and procedures.

“To me, democracy means that when I vote, I should be listened to.”

–Man, Australia

When it comes to voice in government, around one-in-five in each country emphasize that the public has a say in government and the power to influence decisions. One woman in the UK defined democracy as the principle that “everyone in the country of their residence, including myself, deserves our views to be listened to and acted upon.” However, some people note that while this is how they believe democracy should work, the reality is a little different. For example, an Australian man wrote, “We all get a say in how we want this country run. But it doesn’t always mean someone will follow that through if it’s not a popular choice.”

Around one-in-ten in each country focus on the politicians’ role and define democracy in the context of elected officials listening and being accountable to the public. “By the people, for the people” is a phrase that several people included in their definition in both countries.

A relatively small share in each country – 3% in Australia and 7% in the UK – focus less on individuals having a voice and define democracy as majority rule. For example, a man in Australia responded, “Democracy means that if a majority wants it, the majority gets it.” In the UK, one man wrote, “Decisions are made by the majority, whether right or wrong.”

In Australia, younger adults, people who have an unfavorable view of One Nation (a right-wing populist political party) and people with higher incomes are more likely to define democracy as people having a voice in their government. In particular, Australians with higher incomes are more likely to describe democracy as having the power to influence decisions, compared with people with lower incomes. In the UK, definitions do not vary significantly by gender, age, income or views of different parties.

Equality and fairness

Around one-in-ten in both Australia and (11%) and the UK (14%) mention something related to equality or fairness when defining democracy. This includes references to both racial or gender equality as well as more general mentions of fairness, such as those who simply described a “fair society.” Some people were more detailed in their responses, like one Australian who specified that democracy included “fair and equal treatment of people regardless of race, gender or religion.”

In the UK, younger people more frequently mention equality and fairness when describing democracy than older people. One older Briton said democracy means “a society where all members are treated equally and fairly.”

Institutions

Only a small share in both Australia and the UK mention specific institutions when discussing their definition of democracy (5% and 3%, respectively). These respondents see bodies like Parliament or political parties as part of what defines democracy.

For 1% in both countries, Parliament is mentioned as a component of democracy. As one Australian man said, democracy necessitates “established rule of law with the ability to change laws through the parliamentary system.” In Australia, the same share also brings up orderly changes in government. For example, one Australian man emphasized “peaceful transition of power based on results from transparent and free elections.”

A small share of Australians also mention the separation of powers. An Australian woman who included “checks and balances on policies and laws through Parliament” in her definition of democracy is one such example. Other Australians see the court and legal system as part of what defines democracy, such as one man who said democracy is comprised of “the value of equity, justice and due process through transparent mechanisms.”

Societal well-being

“Democracy is ‘a stable, secure, safe and fair way of life.’”

–Man, Australia

Just 3% in both Australia and the UK mention societal well-being in their personal definitions of democracy. Societal well-being generally includes the benefits that may come to people when living in a democracy, such as safety, happiness and harmony with others. Some offered simple descriptions, like an Australian man who said democracy is “peace of mind.” Others explained how democratic institutions and ideals – such as freedom and the voice of the people – foster societal well-being. One Briton defined democracy as “safety and security” and said he feels “secure in the knowledge that progress is made with the consent of the people.”

Democracy is the best system

When asked to define democracy, small shares in the UK and Australia also bring up that democracy is the best political system (6% and 3%, respectively). For example, one Briton said that democracy is “the best way to govern a country.”

“A messy, very flawed system but better than other systems, but I guess it’s like the old joke about communism. It would work if done properly.”

–Man, UK

In a few cases, people specify that democracy is the best political system when compared to other options, or that they feel positively about democracy only because the alternatives are worse. As one British man put it, they consider democracy to be the “least worst system.” Four people in the UK specifically cited Winston Churchill by name when referencing his famous quote about democracy, such as one Briton who wrote, “As Churchill said, ‘Democracy is the worst form of government except all others that have been tried.’ Current implementations of democracy are seriously flawed, but I do not know which is the better system.”

Economic and social benefits

Few Australians and Britons mention economic and social benefits when thinking about what democracy means to them. Just 2% in Australia and 1% in the UK say such benefits are an important part of how they define democracy. For example, one British woman wrote that “having [the] national health system is [a] wonderful thing.” Others wrote that democracy involves investing in education, meaningful employment and providing for basic needs.

Democratic failings

Some respondents in Australia and the UK mention democratic failings in their definitions of democracy (7% and 5%, respectively). One Australian man said democracy is “theoretically good, but it has many problems.” Another said, “Parties cheat and lie to gain power, and once elected, ignore the wishes of the electorate.” When asked to define what democracy means, one British woman put it simply: “Not a lot!”

“Democracy is a false proposition.”

–Woman, Australia

Some respondents point to specific failings in democracy, such as corruption and the influence of special interests or the spread of misinformation and the manipulation of a misinformed public. According to one woman in the UK, “democracy isn’t really possible when the masses are controlled by the media and the elite.” Another British man said democracy is just “elected officials lining their own pockets at the expense of the people.”

Still others define democracy by pointing to its absence in their country. Some respondents said the UK and Australia are “not democratic” and that “real democracy” in their country has not existed during their lifetimes or “is being eroded with the clowns in charge.” Some even went so far as to say: “It’s still a dictatorship. The public have no say.”

“Democracy only functions effectively if the electorate are informed, the media hold the government to account and the government are also accountable to Parliament and the various other political institutions. None of that is the case in the UK right now.” –Man, UK